Socialite, Widow, Jeweller, Spy: How a GRU Agent Charmed Her Way Into NATO Circles in Italy

Three minutes before midnight on 14 September 2018, the cell phone of Andrey Averyanov began to ring. Despite the late hour, phone records show Maj. General Averyanov, the commander of the GRU’s clandestine operations unit 29155, was still in his office at Russia’s military intelligence service headquarters at Khoroshevskoe Shosse 76 in Moscow.

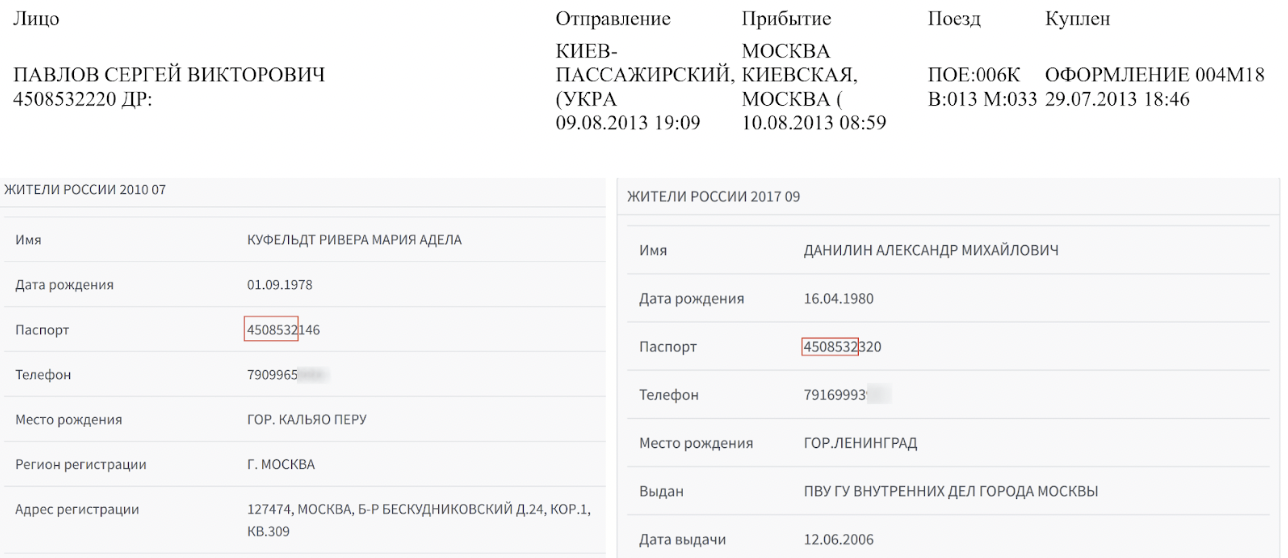

Earlier that day, Bellingcat and its Russian investigative partner, The Insider, had published an investigation into the cover identities of “Ruslan Boshirov” and “Alexander Petrov”, two undercover GRU spies implicated in the Novichok poisoning of Sergey and Yulia Skripal in Salisbury, England. The investigation had blown the lid on a glaring hole in the GRU’s tradecraft: for nearly a decade, Russia’s military intelligence agency had furnished their spies with consecutively numbered passports, allowing investigative journalists who had acquired data commonly leaked onto Russia’s black market to uncover other spies by simply tracing such batches of numbers.

In the hours after Bellingcat’s publication that day, Averyanov had received several phone calls from his top boss – the GRU’s chief Igor Kostyukov. Similarly, Averyanov himself had reached out to many of his subordinates who had been travelling on such passports – including the two spies involved with the failed Montenegro coup in 2016.

The midnight caller was the head of GRU’s Department 5, or the so-called Illegals program – a little-known department that planted military spies around the world under false identities. The two GRU officers talked for just over two minutes.

A Note on Call Record Metadata

In 2019 in the course of investigating the Skripal poisoning, we obtained metadata from call records of Maj. General Andrey Averyanov. These records, spanning the period from mid 2017 to late 2019, shed light on an expansive network of spies run by Russia’s military intelligence. The call data contains location, time and calling party data but no content of the communications.

The next day, 15 September 2018, a woman with a long, Latin-sounding name bought a one-way ticket from Naples, Italy, to Moscow. For around a decade, this individual had travelled the world as a cosmopolitan, Peru-born socialite with her own jewellery line. Later that evening, she landed in Moscow and is not known to have left Russia since. She flew on a passport from one of the number ranges Bellingcat had outed the previous day – in fact, hers only differed by one digit from the passports on which Boshirov and Petrov’s GRU boss had flown to Britain just six months earlier.

The name on her passport was Maria Adela Kuhfeldt Rivera, and as Bellingcat and its investigative partners have discovered, she was a GRU illegal whom friends from NATO offices in Naples had for years believed was a successful jewellery designer with a colourful backstory and chaotic personal life.

Image credit: Ann Kiernan

This joint investigation by Bellingcat, Der Spiegel, The Insider and La Repubblica, was conducted over the course of 10 months. It is based on data from open sources, publicly accessible archives, FOIA data from Peru, leaked Russian databases and interviews with people who had unsuspectingly befriended the Russian spy. Most of the people agreed to be named despite initially fearing speaking publicly about an individual they now understand to be a GRU spy. Yet some of those who spoke did so only on the condition of anonymity because of these concerns.

Inventing ‘Maria Adela’

On 8 August 2005, the Civil Registration office of the Independencia District in Lima, Peru, received an application for inscription of a new Peruvian citizen into the country’s national citizen database. The would-be citizen stated that her name was Maria Adela Kuhfeldt Rivera, and her lawyers presented a birth certificate from the civil registry of the seaside town of Callao. The birth certificate was dated 1 September 1978 and carried the sequential number 1109 on Peru’s record of births for that year.

According to a letter from the Peruvian civilian registry reviewed by Bellingcat, the civil officer handling the case put the application on hold and requested additional evidence for the actual birth of Maria Adela.

On 19 August 2005, “Maria Adela”’s lawyers submitted an extra document: a baptism certificate from the Cristo Liberador parish in Callao. According to the church document, baby Maria Adela was born on 1 September 1978, and was baptised two weeks later, on 14 September 1978.

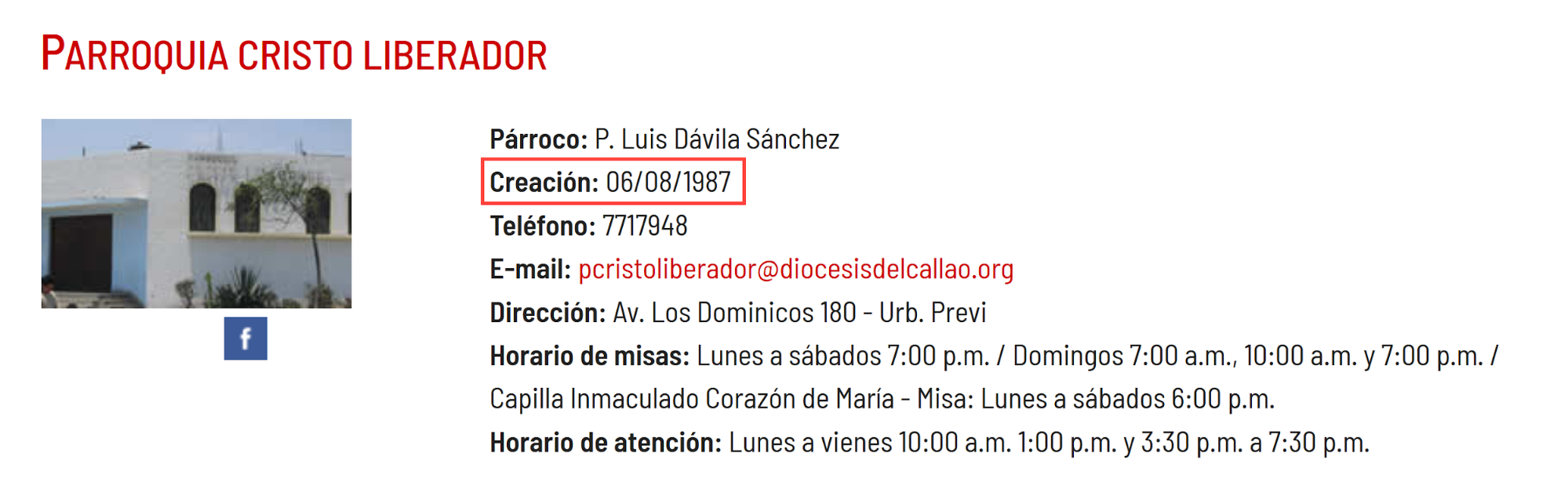

The Lima civil officer was not convinced and reached out for verification to the parish priest at the Cristo Liberador dioceses, the Rvd. José Enrique Herrera Quiroga. Unluckily for the citizen-in-waiting, the priest would not even have had to check the church records to report that the document was fake. He had had the honour of being the founder and inaugural priest at this church which was established in 1987, nine years after the supposed baptism of Maria Adela had taken place. The website of the Cristo Liberador dioceses details the date it was founded, something a representative of the parish confirmed when Bellingcat contacted it.

A screen grab from the Diocese del Callao website details when the Christ Liberador church was formed.

On 22 December 2006, in an annual budget report to the Congress of Peru, the Peruvian Ministry of Justice reported that its migration and naturalisation office had discovered three fraudulent citizenship applications in 2005, one of them being that of “Maria Adela”. The report concluded that this person’s identity is unknown and referred the case as a crime against public safety and faith to the national prosecutor.

Take Two: The Moscow Olympic Child

Even though Maria Adela’s Peruvian citizenship was stillborn, her GRU commanders – likely unaware that the Peruvian government would make this false start public – decided to persist with this identity for their spy. The reason for their persistence is unknown.

Whatever it was, “Maria Adela” received her first Russian passport in 2006, using exactly the same name and birth date. According to the cover identity that was created for her, she worked as a “leading specialist” at Moscow State University and lived at a Moscow address as far back as 2010, according to registration databases. Those who live there now told us they had never heard of her.

Notably, the domestic Russian passport issued to “Maria Adela” belonged to a range that GRU had issued for domestic passports of at least six other GRU spies, including an officer indicted in the poisoning of Bulgarian arms manufacturer Emilian Gebrev, and another officer involved in the poisoning of Sergey Skripal. Based on the proximity of the passport numbers and the known issuance date of the other passports, we can estimate that “Maria Adela” received her Russian identity papers in November or December 2006 – just before the Peruvian Ministry of Justice would publicly burn her identity, albeit on a little visited website.

“Sergey Pavlov”, real name Sergey Lyutenko (top), and “Alexander Danilin”, real name Alexander Kovalchuk (left), known GRU officers, had passports differing from that of “Maria Adela” (right) in the last three digits only as shown in the above images.

Based on interviews with four people whom “Maria Adela” befriended in the next decade, she told those she met the following back story of her name and origin: she was the love child of a German father and a Peruvian mother, and was born in Callao, Peru. Her single mother had travelled with little “Maria Adela” to the Soviet Union in 1980, to attend the Olympic Games in Moscow. However, her mother had received an emergency message from Peru that required her to return home urgently – and left little “Maria Adela” in the care of a Soviet family that she had apparently befriended.

Her mother never returned, and “Maria Adela” grew up in Russia, having a difficult relationship with both her adoptive mother and her father, who – she told people – abused her in her childhood years. The latter, she told people she befriended, was the reason she did not want to live in Russia – or marry a Russian man – and explained her desire to live and create a family in Western Europe.

Rome, Malta, Paris

Bellingcat was unable to discover travel data for “Maria Adela” prior to October 2011 due to the partial nature of the available trip databases. However, a scattering of social media posts showing her in other people’s photos place her in Malta and Rome in the period between 2009 and 2011.

Marcelle D’Argy Smith, former editor of the UK edition of Cosmopolitan magazine, became close friends with “Maria Adela” whom she met over drinks in Malta in the summer of 2010. “Maria Adela” lived in Malta with her then boyfriend, but at some point moved to Ostia, near Rome, to take classes in gemology. Maria tried hard to obtain a German passport on account of her German father, Ms. D’Argy Smith said, but the process stalled after “Maria Adela” suddenly appeared to lose interest.

“Maria Adela”, centre, with friends including Marcelle D’Argy Smith in Malta in 2010. Photo courtesy Marcelle D’Argy Smith.

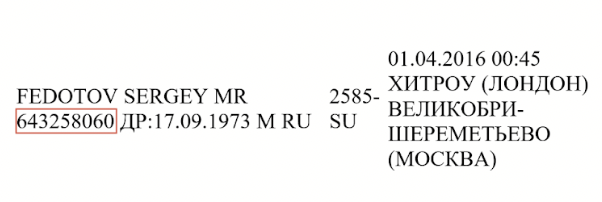

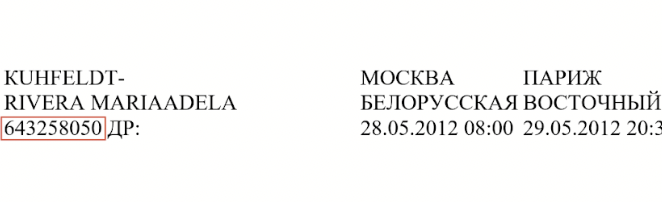

The earliest international travel records for “Maria Adela” found by Bellingcat are from 10 October 2011, when she took the first of many two-and-a-half-day train rides from Moscow to Paris via Belarus. The passport she travelled on during this trip and over the next few years was issued in August 2011 and had the number 643258050 – only a few numbers away from that of “Sergey Fedotov”, one of the senior officers GRU’s black-ops unit 29155.

A comparison of passport details belonging to “Maria Adela Rivera Kuhfeldt” (top) and Sergey Fedetov (bottom).

According to Marcelle D’Argy Smith, “Maria Adela” initially studied gemology at a university in Rome, and travelled to the UK in February 2011 on a school-organised trip to various fashion design companies. In October 2011, “Maria Adela” moved to Paris to pursue an MBA. Italian immigration data obtained by La Repubblica and reviewed by our team corroborate Ms. D’Argy Smith’s recollections, and show that “Maria Adela” initially travelled on short-term French visas, ultimately obtaining a student visa in September 2011.

It was shortly after she moved to Paris that she registered her own jewellery trademark in France under the brand Serein.

This was likely the seeding phase of a long-term plan by the GRU to deploy their illegal spy as a self-sufficient businesswoman and socialite. In the years that followed, it provided cover as she sought to access the highest echelons of NATO’s Allied Joint Force Command in Naples, Italy.

A Short-Lived Marriage

In July 2012, “Maria Adela” married a man who she told friends was an Italian, three of her acquaintances told our reporters. In reality, in addition to an Italian passport, her husband held Ecuadorian and Russian citizenship and was born in Moscow to a Russian mother and a father from Ecuador.

Leaked Russian travel and migration data and open-source data from the husband’s social media page show that in April 2012, just before their wedding, he obtained a Russian passport from the Embassy of Russia in Ecuador. After the marriage was registered in Rome, Italy, he travelled to Moscow where he obtained a Russian tax identification number in September 2012.

A year later, he travelled to Moscow again, separately from “Maria Adela”. He died in Moscow on 13 July 2013 aged 30, the cause of death recorded in the death certificate as “double pneumonia and systemic Lupus”.

Border crossing data show that “Maria Adela” was not in Russia during her new husband’s death, and only arrived in Moscow a month later, on 15 August 2013. A close friend of his who agreed to talk to The Insider on the condition of anonymity due to concerns for their own safety around discussing the topic given “Maria Adela’s” role as a spy was surprised to learn that he had married without telling his friends, and conjectured that he may have agreed to a marriage of convenience in order to help someone obtain a European passport. The friend also told the Insider that he was diagnosed with Lupus less than two months before his sudden death. [Systemic Lupus is a connective tissue disease of unknown causes which, according to medical literature, is rare among young men].

The Merry Widow of Naples

Following her marriage, in early 2013 “Maria Adela” registered her own company in Italy – Serein SRL, its corporate goal listed as production and trade of jewellery and luxury items. As seen from a residence permit issued by the Naples police and obtained by La Repubblica, no later than October 2015 she had moved to the elegant Posillipo district of the coastal city with a view on the Gulf of Naples.

It was in Naples that “Maria Adela’s” career as a Russian illegal spy peaked. Over the next three years, she became a fixture on the local social scene. She opened a jewellery and luxury items boutique, later turning it into a trendy club frequented by the local highlife, and eventually becoming the secretary of a charitable organisation that was also attended by members of the NATO command centre in Naples.

“Maria Adela”’s boutique carried branded jewellery from the Serein line that she claimed to have designed herself. The now-defunct webpage of her company described Serein jewellery as “created for the elegant woman who is never excessive.”

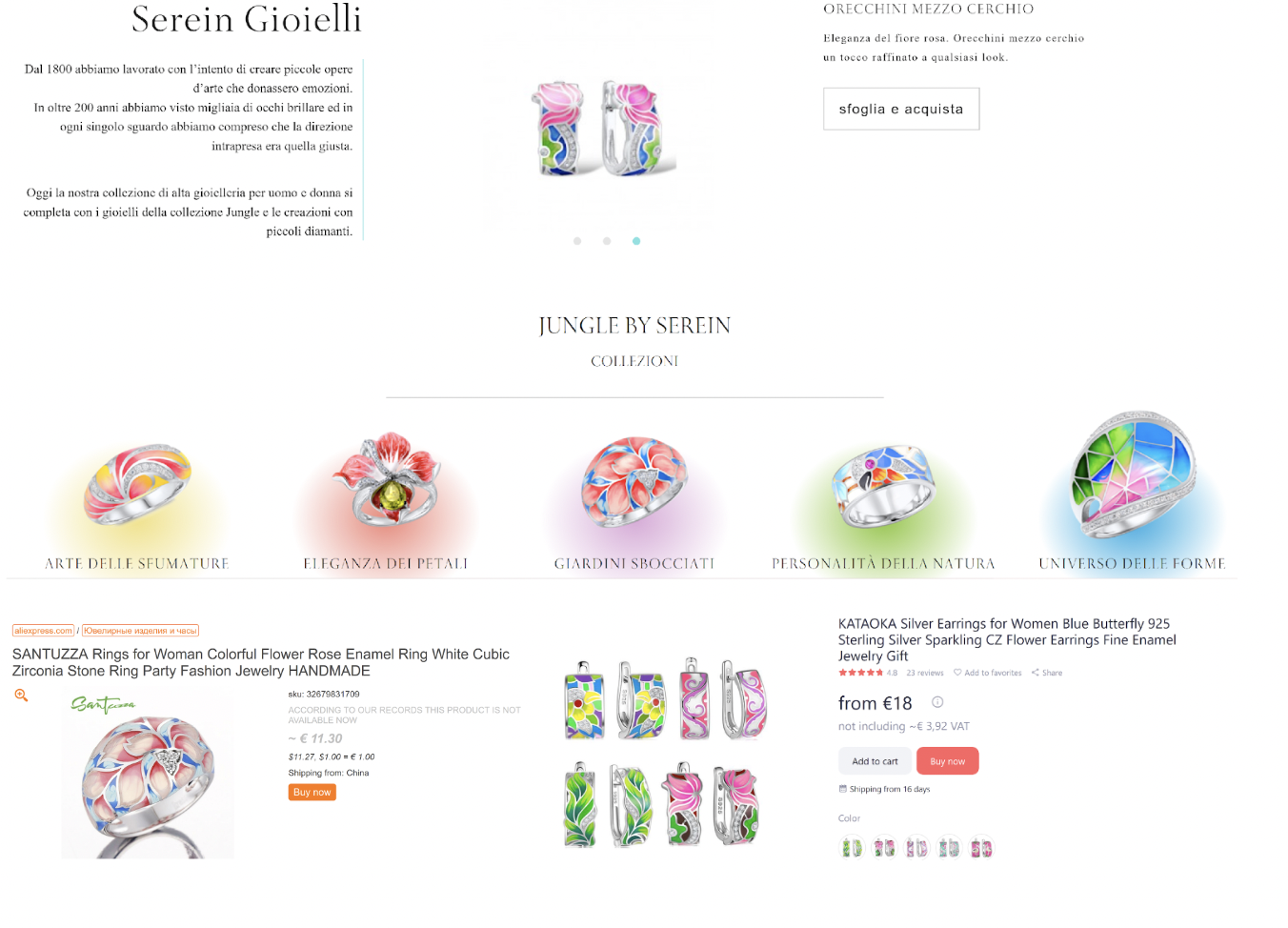

In fact, a reverse image-search shows that the colourful self-branded jewellery sold in “Maria Adela’s” boutique and touted on the website as “made in Napoli” appeared to be inexpensive jewellery purchased from Chinese online wholesalers.

Items detailed for sale by “Maria Adela’s” Serein brand (top) appear to match those for sale on wholesaler sites (bottom).

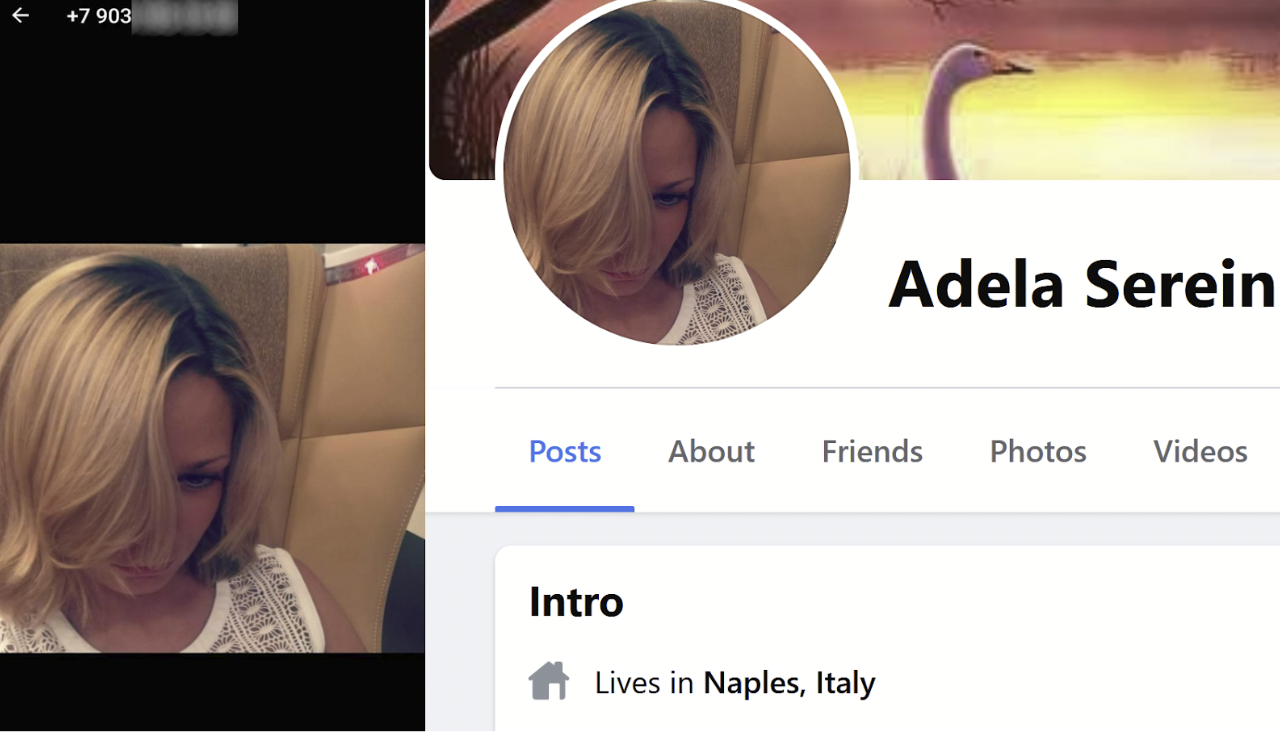

This did not prevent “Maria Adela’s” ascent in Naples society as a trendy jewellery designer and socialite – going socially by the name of Adela Serein, according to friends, she and her gallery were featured in local media such as this promotional video lauding the launch of “the Serein Concept Gallery”. A local newspaper report at the time detailed the attendance of local councillors, entrepreneurs and celebrities.

Running The Lions Club

“Maria Adela’s” social reach, however, was not limited to the Naples in-crowd.

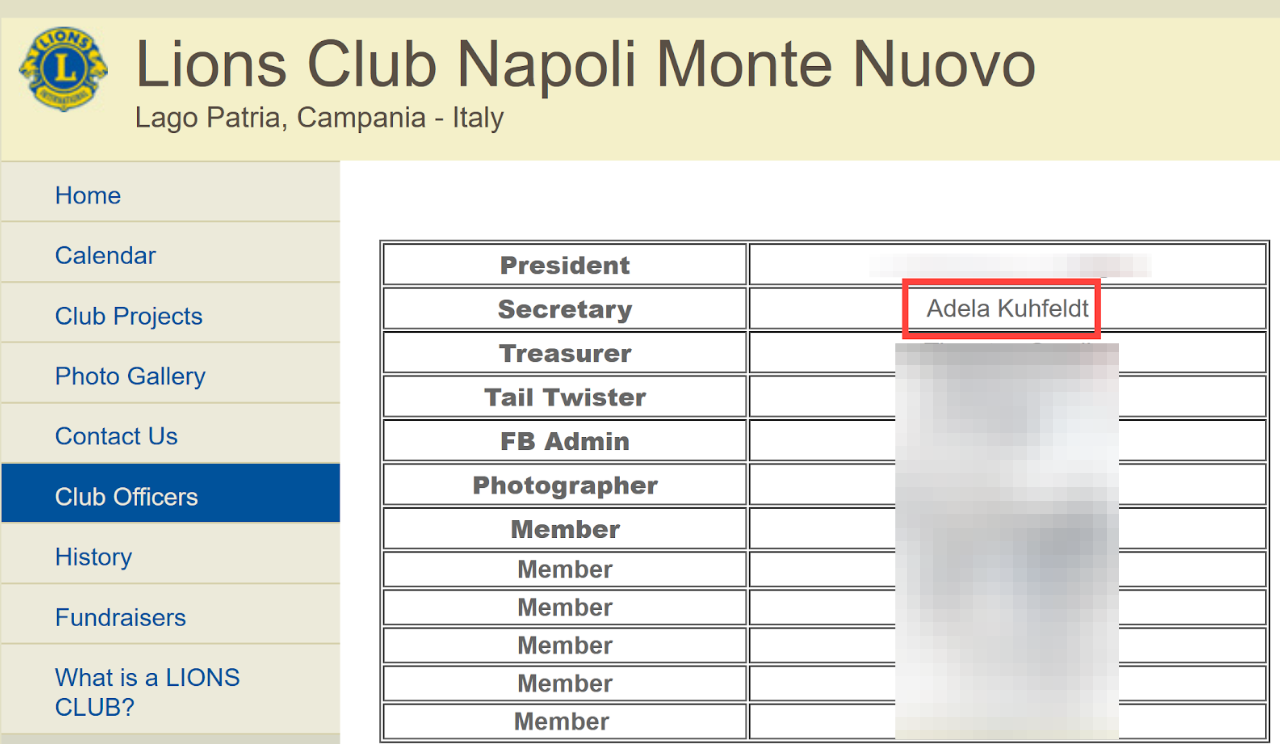

At some point in 2015, “Maria Adela” became the secretary – and one of the most active members – of a local charitable organisation – the Lions Club Napoli Monte Nuovo. This was not just a regular branch of the Lions Club, an organisation that spans the globe and which looks to better the communities it operates in and advance civic society. It had initially been established by a Naples-based NATO officer.

According to Oberstleutnant Thorsten S, a German Bundeswehr officer who in 2015 was treasurer of this Lions Club branch, the club’s membership had waned in previous years and an executive from the biggest Lions Club in Naples recommended “Maria Adela” as a way to invigorate the membership by adding a vibrant international connection. The Oberstleutnant spoke on condition he was quoted using only the first initial of his surname as is required of Bundeswehr staff when speaking to the media. He remembers that “Maria Adela” was very active in trying to reinvigorate the club’s activities, attended all events, and at one point in 2018 – as membership declined and prospects of club closure re-emerged – even volunteered to pay everyone’s membership fee. Oberstleutnant Torsten S said he never understood her motives to do so.

“Maria Adela” is listed as secretary of the Lions Club Monte Nuovo (top). “Maria Adela” can be seen with other members of the Lions Club in a picture posted to the organisation’s website.

Three NATO-affiliated acquaintances of “Maria Adela” interviewed by the investigative team said that in her role at the Lions Club, she interacted with many NATO staff, befriended a number of NATO officers and had frequent social interactions with them. One NATO employee who spoke to investigators on the condition of anonymity admitted to having a brief romantic relationship with Maria Adela. Her love-life was also a topic “Maria Adela” addressed with friends. In an email shared with Bellingcat by Marcelle D’Argy Smith, “Maria Adela” wrote that a US Navy employee she had met in Naples and who was a photographer had “a little crush” on her.

But not all of the relationships she struck up were of a romantic nature, far from it. One of the people perceived as friendly with “Maria Adela” was Col. Shelia Bryant, then Inspector General for the U.S. Naval Forces in Europe and Africa. Ms. Bryant, who left Naples in May 2018 and ran for congress as a Democrat, says she found “Maria Adela’s” back story confusing and unconvincing (“why would anyone abandon their child in the Soviet Union?”), and her continuous source of income hard to explain (“she opened a store and frequently moved apartments in affluent parts of town with no credible income streams”). Ms. Bryant says she and her husband contained their communication with “Maria Adela” to social interaction, trying to help her through what appeared to be emotional issues with men. This perception was echoed by Marcelle D’Argy Smith and one other acquaintance of “Maria Adela” who spoke to Bellingcat on condition of anonymity. Ms. Bryant says they did not discuss politics with “Maria Adela”, and that she herself had limited access to highly confidential military information on a need-to-know basis. In her recollection, “Maria Adela” interacted socially not only with American but also with Belgian, Italian and German NATO staff and officers.

Ms. Bryant said she and her husband were introduced to “Maria Adela” by the wife of a US government contractor stationed in Naples. Reporters repeatedly attempted to contact this woman, but she blocked the Bellingcat investigator after being approached via Facebook, and rejected phone calls from Der Spiegel reporters.

Another person who was described by Oberstleutnant Thorsten S as close to “Maria Adela” – before they fell out with one another in 2018 – was a data systems administrator at the NATO command centre in Naples. This person – who is no longer with NATO – initially agreed to talk to Der Spiegel. However, once they found out the topic of the investigation they no longer responded to calls or messages from either Der Spiegel or Bellingcat.

While “Maria Adela” certainly had direct personal access to many NATO and US Navy officers at Naples – and exchanged home visits with several of them – it is not clear if she ever got physical access to the NATO base. Based on a variety of digital breadcrumbs and recollections from acquaintances, she however did attend many events organised by NATO or the US military – including NATO annual balls, various fund-raising dinners and the annual US Marine Corps balls. She also invited her acquaintances from NATO to her store, and at least one of them remembered having bought items from it.

Bahrain and Beyond

Recollections from Ms. D’Argy Smith and social media postings on “Maria Adela”s Facebook, as well as on that of her company, show that as of 2013 she regularly travelled to Bahrain, under the pretext of attending an annual luxury goods and jewellery expo, Jewellery Arabia. Travel itinerary from 2013 she shared with Ms. D’Agy Smith by email show that she stayed in Bahrain from 17 November to 24 November that year.

Following her trip, she emailed Ms. D’Argy Smith, writing”

“.. . in Bahrain everything went well, except we didn’t sell… But the trade show was great, I love the country and people I met. After I came back in five days [I] had to fly to Moscow as my mother didn’t feel well. I stayed there for a week and then came back to Italy. Now working on the catalogue and improvement of the pieces. Around Christmas [I] have to go to Moscow again as my mother is still not doing well.”

A scan of a Bahrain newspaper article mentioning “Maria Adela Rivera Kuhfeldt”, and a photo of her at the expo, both were emailed to Marcelle D’Argy Smith in December 2013.

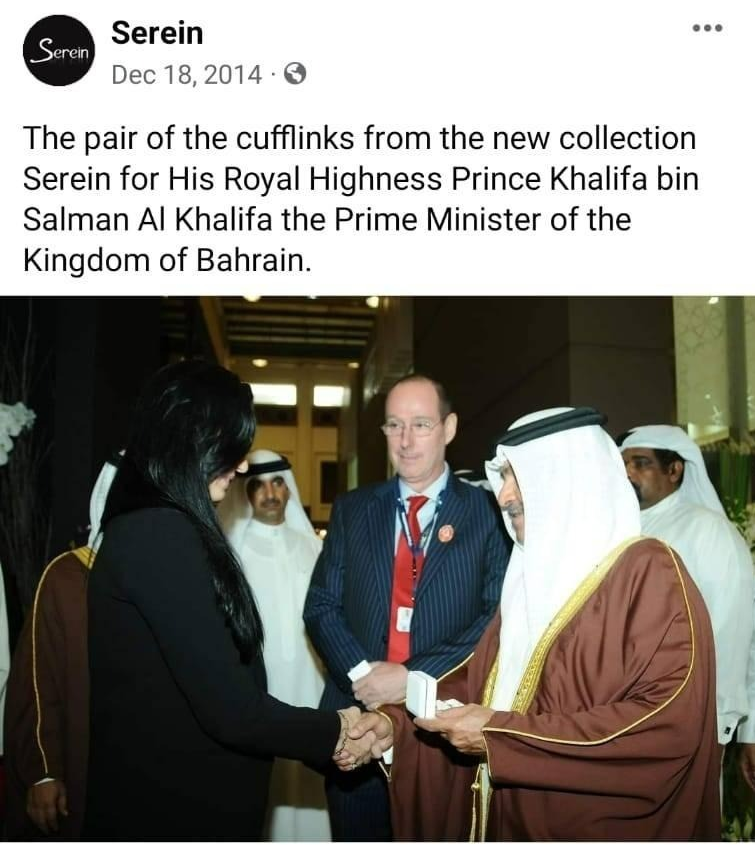

In December 2014, her company’s FB account posted a photo in which she can be seen seemingly gifting Serein cufflinks to the country’s then prime minister, Prince Khalifa bin Salman Al Khalifa.

A post on the Serein Facebook page appears to show “Maria Adela” meeting with Bahrain’s then prime minister, Prince Khalifa bin Salman Al Khalifa, in 2014.

The last known time “Maria Adela” likely travelled to Bahrain was in 2017, based on an email sent to Marcelle D’Argy Smith in August 2017 in which she said she was then expecting her Italian residence permit renewal and had booked travel to Bahrain and then on to Moscow in the middle of November that year.

While the investigative team could not establish “Maria Adela”s movement and communication networks inside Bahrain, it is perhaps notable that the country is the home to United States Naval Support Activity Base and to U.S. Naval Forces Central Command and United States Fifth Fleet. The base hosts over 7,000 US officers and troops.

Bahrain was not the only destination outside Naples that “Maria Adela” said she had travelled to for ostensibly business reasons. In addition to trips to jewellery or luxury exhibitions – in Switzerland and Germany, she also told at least one friend she had planned travel to Thailand. In an email she sent Ms. D’Argy Smith in June 2014, “Maria Adela” said that she would be visiting the Southeast Asian nation “in a couple of weeks” to try and establish production for her jewellery line there. However, investigators were not able to find any open source information corroborating such a trip.

A Hurried Departure

In 2018, the fictitious “Maria Adela” flew back to Moscow one last time. On this occasion, however, she travelled on a new, third Russian passport. Like the previous two, this passport used a number from the GRU-assigned batches.

Her usually active social life evaporated, and none of the acquaintances that reporters spoke to remembers being informed by her of her plans to leave Italy for good, or the reasons for such a decision. The only memento from her prior life that “Maria Adela” brought home with her, border records show, was a cat. “Maria Adela” had a black cat called Luisa, which two of her acquaintances described to our team as the only stable thing in her life.

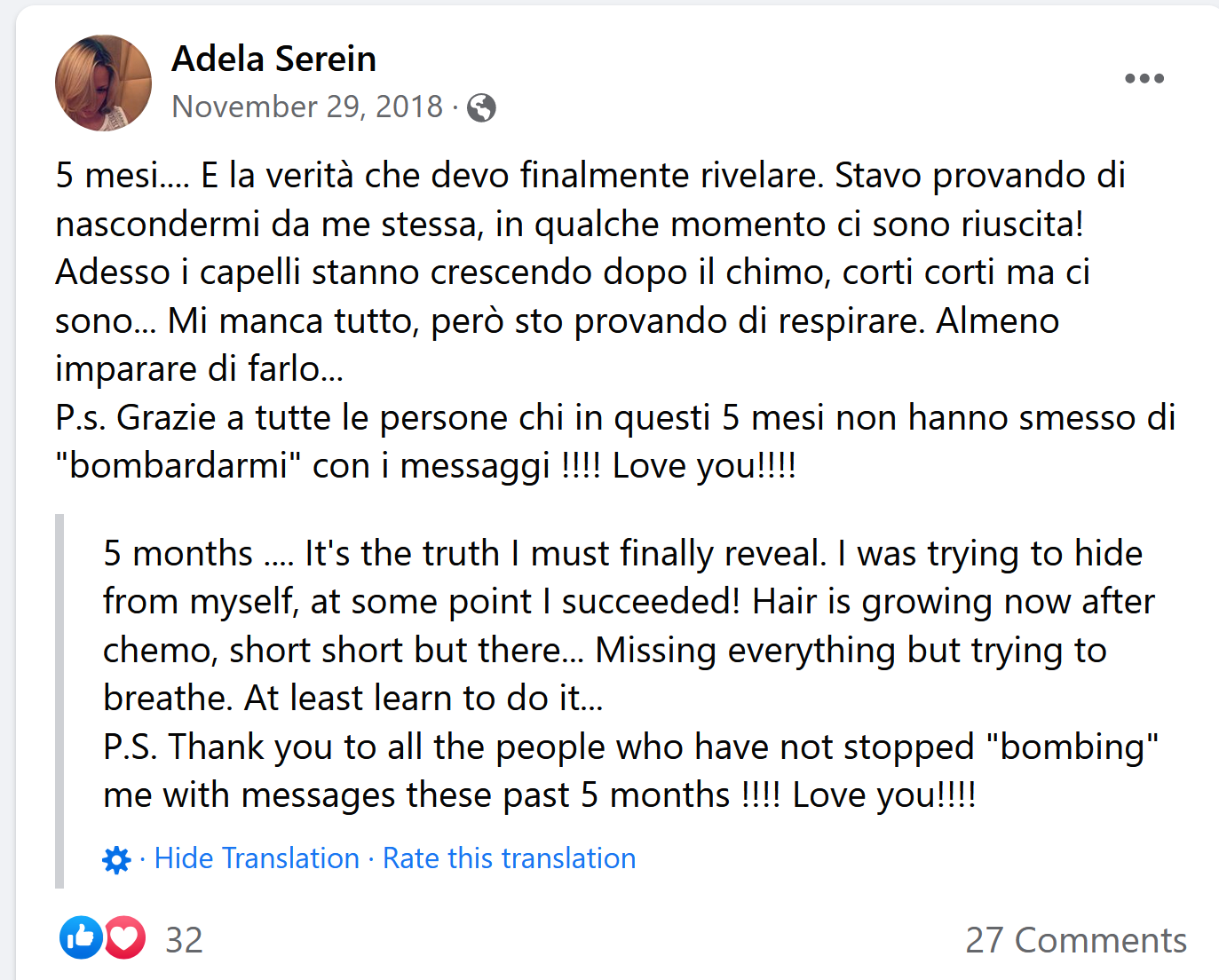

Two months after her departure, however, she posted one last cryptic, yet leading post on her Facebook page. In it, she alluded to having suffered from cancer, and talks about her hair growing back “after chemo”.

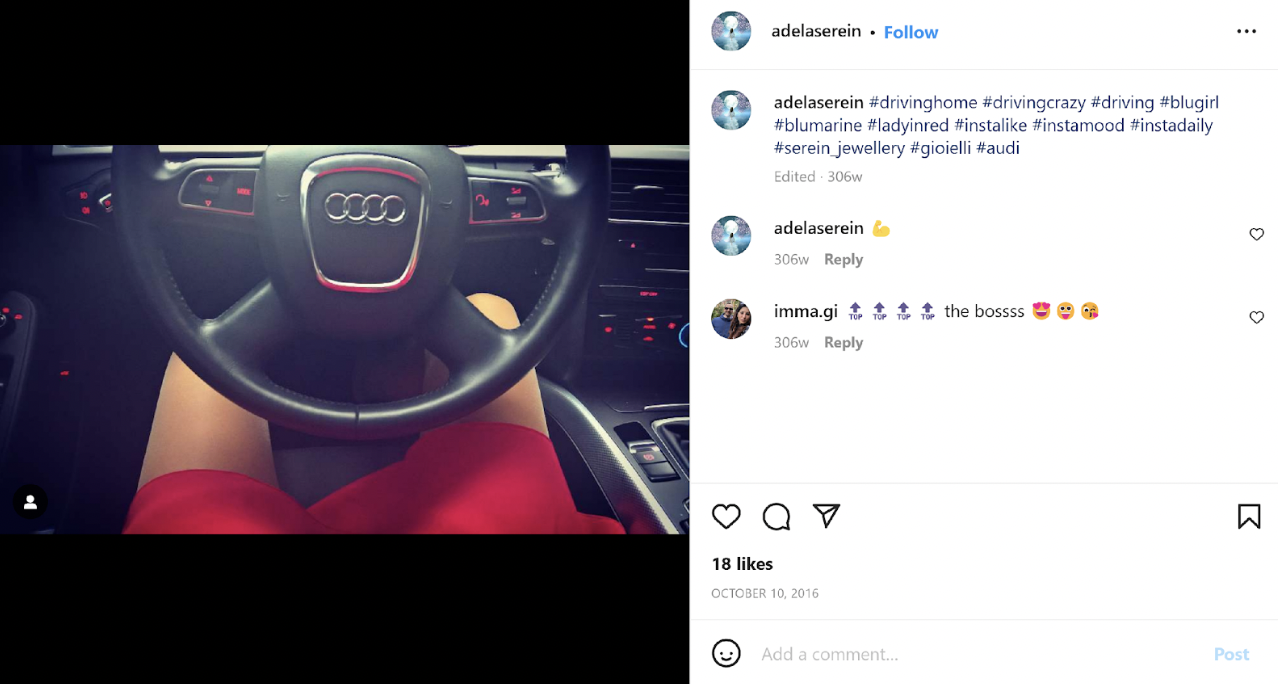

In fact, at the time the fictitious person that her shocked and worried friends knew as “Maria Adela” wrote this message, the real woman – a GRU officer named Olga – was spending time behind the wheel of her latest-model Audi car and eying a move into brand-new, luxury apartment in an upscale Moscow neighbourhood.

Just over three years after disappearing from Naples, on 4 December 2021 “Maria Adela” sent one more cryptic message, this time in a direct WhatsApp chat with Marcelle D’Argy Smith. The message read:

“ Dearest dearest Marcelle!

There are [a] lot of things which I can’t (and never be able) to explain!

But missing you a lot and very very much….”

Hunting for the Real “Maria Adela”

Bellingcat and its investigative partners established the then apparent affiliation of “Maria Adela” to the GRU late in 2021, based on several indicators that made her cover identity and behaviour compatible with the modus operandi of Russia’s military intelligence. First, a person with such name and birth date did not exist in any Russian (current) databases – including the comprehensive official passport database – but her name did appear in a leaked 2007 passport and address dataset where we had previously found other GRU officers listed under their cover identities. She had been issued at least three passports – one domestic and two international travel passports – from ranges used by many other known GRU officers. Her cover identity was that of a mixed-ancestry South American-born person – which was a favoured back story both for Russia’s Foreign Intelligence Service, the SVR, and GRU illegals, as evidenced recently by the capture and deportation of a confirmed GRU officer who had lived for years in the US and Ireland as a Brazilian with a German father. While theoretically that opened up the possibility that “Maria Adela” was an SVR illegal, the passport range overlap plus the apparent interest in NATO made the GRU affiliation much more plausible.

However, our team struggled for months to find any clue to her real identity. There were no photographs of this person on Russian social media, thus reverse face searches produced no results. The Russian telephone numbers that had been listed as contacts for her fake identity in her 2007 “identity creation” paperwork were registered to an “anonymous person” (which was another indication of her affiliation with a secret service, as all numbers in Russia must be registered in the name of a real person).

A reverse face-search in Russia’s sprawling passport database led to no matches with a persuasive confidence of facial similarity. However, it did produce hundreds of possible low-score matches that our team began analysing to identify other possible overlaps.

It was a deep-dive analysis of one of these low-score facial matches that ultimately resulted in the identification of the real person behind “Maria Adela”.

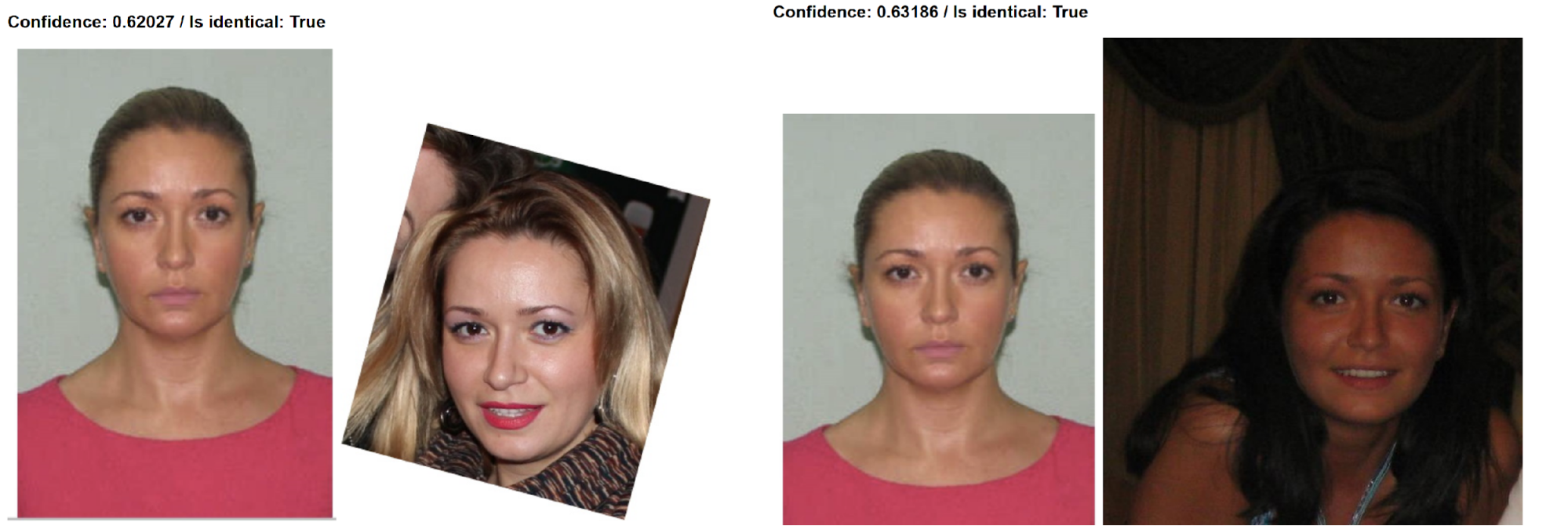

A comparison of two images in the Microsoft Azure facial recognition tool brings back a negative result but was further explored by investigators.

A comparison of two different-age photographs of “Maria Adela” from social media sources to an old passport photo of a Russian citizen by the name of Olga Kolobova, born in 1982, in Microsoft’s Azure tool gave unimpressive scores of less than 35%. After initially discarding this person as an unlikely suspect, reporters revisited this hypothesis due to the old vintage of the passport photo, likely showing the person at the age of 14 or 15.

Indeed, the non-visual compatibility between the two personas soon became strikingly intriguing. First, Olga Kolobova had no digital footprint in Moscow prior to 2018. Not a single address registration, traffic violation, or phone number registration were discovered in any of dozens of leaked Moscow databases. However, this person had a very active digital presence that began in November 2018 – just about the time when “Maria Adela” would have returned to Moscow.

Other circumstantial similarities began appearing. In November 2018, Olga Kolobova had purchased her first car in Russia, databases showed: it was a brand-new, 2018 model of an Audi 3. Incidentally, “Maria Adela’s” Instagram showed a POV photograph of her behind the wheel of an Audi in 2016, suggesting a penchant for this model of car.

We then discovered a social media account on Russia’s Odnoklassniki (OK) platform that in 2019 was registered with the name and birthdate of Olga. In addition to promoting pro-war content from a group called “Friends of Putin”, she was a member of only one other group on OK – that of a vet clinic in Moscow that catered to, among other animals, cats.

Using old leaked databases from cities outside Moscow, we ultimately were able to track down Olga’s previous digital presence in Russia to 2005, when, aged 23, she had registered a company trading in alcohol in the Krasnodar region in Russia. Tracing her then address registration, we were also able to track down her father. We discovered that he had been the Head of the Military Faculty at the Urals University in Ekaterinburg until he retired in 2007. More intriguingly, his school website boasted that he, a colonel in Russia’s armed forces, had received numerous distinctions and medals “for his service to the Fatherland abroad, including in Angola, Iraq and Syria”. Based on findings from previous investigations that GRU spies are frequently recruited from among children of high-ranking military officers, including with intelligence backgrounds, this added further credence to the possibility that “Maria Adela” and Olga were the same person.

This hypothesis was also reinforced by the fact that Olga Kolobova had become the owner of two apartments in Moscow during periods when “Maria Adela” was in Russia. The first one – a small studio in a prestigious location, was acquired during one of “Maria Adela’s” trips to Russia in April 2013. The second, a luxury 100 square metre apartment in a high-end residential complex – valued at approximately EUR 800,000 based on comparable offerings – was acquired in 2020. At the same time, leaked food-delivery data from YandexFoods showed that Olga had been ordering food during working hours to an address housing Russia’s Pension Fund. On the assumption that she works as a clerk at the pension authority, the provenance of the significant funds to acquire these apartments appeared very unclear.

Led by all of these clues, our team was able to obtain a fresh photograph of Olga Kolobova from a whistleblower with access to Russia’s database of drivers’ licences. That photo – which appeared to be from 2021 – provided a convincing match between the faces of “Maria Adela” and Olga Kolobova.

A positive match between photographs of “Maria Adela” and Olga Kolobova using the Microsoft Azure facial recognition tool.

However, facial recognition software, while useful, is not sufficient to prove conclusively that two individuals are the same person in an investigation such as this. Reporters then searched for Olga’s phone number on WhatsApp and found solid proof that Olga and “Maria Adela” were indeed the same person.

The picture that “Maria Adela” had used as her Facebook profile had also been used by Olga as her profile image on WhatsApp. “Maria Adela” had also posted the picture to her Instagram page.

This, alongside all the other overlaps was enough to reveal “Maria Adela’s” true identity. But what about her GRU affiliation? This was strongly suggested by the passport numbers being in the range of other GRU agents, the South American backstory that had been used by at least one other GRU illegal and her father’s previous affiliations. However, we decided to obtain telephone metadata records for Olga Kolobova’s number to see if any further corroboration could be found.

On 23 February 2022, Russia’s day of Defenders of the Motherland, universally celebrated among military officers, Olga called a number that was familiar to our investigation team. It was none other than the number of the same commanding officer from Department 5 of GRU who had placed the midnight call to Gen. Averyanov four years earlier.

Mission Success or Mission Aborted?

Olga Kolobova’s nearly decade-long service as an illegal is unusual compared to other known cases of Russian deep-cover spies for several reasons. One of these is the self-imposed termination of her deployment, without her being caught by foreign counter-intelligence service. This leaves open the question whether GRU perceived her stint in Europe as a success or a failure. In comparison with other known Russian illegals who lived for decades in the West and were only able to establish marginally interesting networks of contacts, “Maria Adela’s” network – mingling with NATO and US Navy officers, including some who would have had access to on-base photographs or confidential legal files and databases appears impressive, at least on paper. During her deployment, Kolobova travelled extensively under the guise of visiting exhibitions and friends throughout Europe, Bahrain and potentially Thailand. This capability in itself could have been useful to the GRU.

There is no evidence that Western counter-intelligence services or NATO’s own internal security service were aware of the presence of a Russian military spy placed strategically close to NATO’s Joint Force Command Center in Europe. None of “Maria Adela’s” acquaintances we spoke with – all of whom could be traced to her via open-source data – had been approached by either NATO or law-enforcement to be debriefed about their interaction with the Russian.

The Insider and Der Spiegel approached Olga Kolobova for her comments via Telegram and email. While the Telegram messages sent to her appeared to be seen, she did not respond.

Der Spiegel also approached the NATO spokesperson for comments. By press time the NATO office had not replied.

Bellingcat is a non-profit and the ability to carry out our work is dependent on the kind support of individual donors. If you would like to support our work, you can do so here. You can also subscribe to our Patreon channel here. Subscribe to our Newsletter and follow us on Twitter here.