Frontex at Fault: European Border Force Complicit in ‘Illegal’ Pushbacks

Vessels from the European Border and Coast Guard Agency, Frontex, have been complicit in maritime “pushback” operations to drive away refugees and migrants attempting to enter the European Union via Greek waters, a joint investigation by Bellingcat, Lighthouse Reports, Der Spiegel, ARD and TV Asahi has found.

Open source data suggests Frontex assets were actively involved in one pushback incident at the Greek-Turkish maritime border in the Aegean Sea, were present at another and have been in the vicinity of four more since March.

Although Frontex assets were not at the immediate scene of those latter four incidents, the signature of a pushback is distinctive, and would likely have been visible on radar, with visual tools common on such vessels or to the naked eye.

The Greek Coast Guard (HCG) has long been accused of illegal pushbacks.

These are described by the European Center for Constitutional and Human Rights (ECCHR), a legal and educational non-profit, as incidents where refugees and migrants are forced back over a border without consideration of individual circumstances and without any possibility to apply for asylum or to put forward arguments against the measures taken.

In the Aegean Sea, pushbacks generally occur in two ways. The first type is the most common: Dinghies travelling from Turkey to Greece are blocked from landing on Greek soil by the HCG. This could mean either physically blocking the dinghy until it runs out of fuel, or disabling the engine. After the engine no longer works the dinghy can then either be pushed back into Turkish territorial water with waves, or towed if the wind is not favourable.

The second type of pushback is employed when people have managed to land on Greek soil. In this case they are detained, placed in a liferaft with no means of propulsion, towed into the middle of the Aegean Sea and then abandoned.

Pushbacks will often result in standoffs between the HCG and Turkish Coast Guard (TCG), both of which will standby, refusing to aid dinghies in distress and carrying out unsafe manoeuvres around them.

The role of Frontex assets in such incidents, however, has never been recorded before.

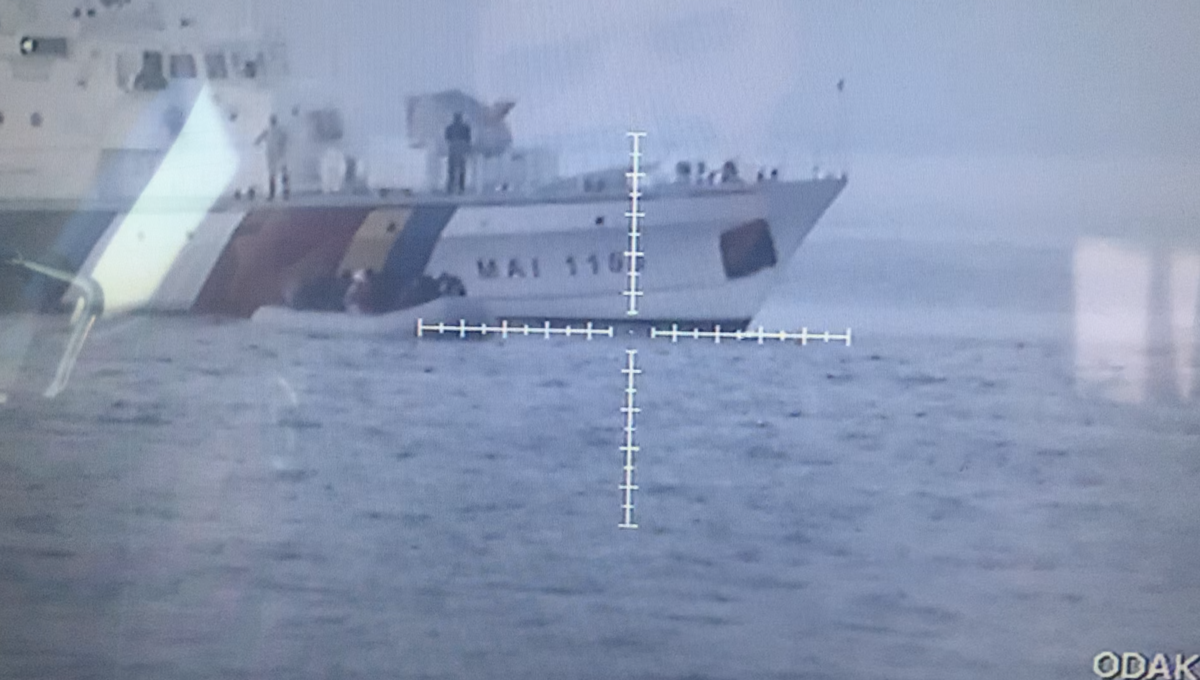

Still from TGC video that shows a Frontex vessel approaching a dinghy in the Aegean Sea on June 8, 2020.

Dana Schmalz, an international law expert at the Max Planck Institute in Heidelberg said the incidents highlighted in this investigation were likely “illegal” and “violate the prohibition of refoulement and maritime law.” The prohibition of refoulement refers to rules banning the forcible return of refugees or asylum seekers and is described by the UN Refugee Agency as a “rule of customary international law.”

Schmalz added that if Frontex personnel stopped an overcrowded dinghy of the type seen in footage documented during this investigation, they would be obliged to rescue its occupants immediately. “If they don’t do that, even make waves [or] instead drive away and then let the Greeks do the dirty work – then they are involved in the illegal pushback.”

Despite being presented with numerous examples of the practice, a spokesperson for the Greek Maritime Ministry Greek denied claims of pushbacks, describing allegations of illegal actions relating to the incidents documented in this article as “tendentious.” They added that HCG officers act in compliance with the country’s international obligations.

Frontex said that the host states it works with have the final say in how operations on its territory or search and rescue zone are carried out. However, it added that Frontex had notified HCG which confirmed an internal inquiry had been launched into each of the reported incidents. Yet Frontex did not say when it notified HCG or when the inquiry had begun.

On July 24, the director of Frontex, Fabrice Leggeri, told the Committee on Civil Liberties, Justice and Home Affairs (LIBE) at the European Parliament that the agency had observed and recorded just a single incident which may have been a pushback in the Aegean.

Our investigation — which looked at the presence of Frontex assets in the Aegean Sea and observed their movements over many months — appears to contradict that assertion.

This was despite the difficulty in tracking many Frontex assets because their transponder information was either not registered, not turned on, or was out of range. As such, we were only able to view a snapshot of Frontex operations.

Frontex, an agency of the European Union, is tasked with border control of the Schengen Area. Its activities in the Aegean are called Operation Poseidon.

How we Recorded Pushbacks: Identification of Assets

There were two main steps to establishing that Frontex had participated in pushback operations. The first was to identify what assets had been deployed in Operation Poseidon. The second was to establish whether these assets had participated in pushback operations.

The first step was carried out using open sources. These included social media posts, vessel tracking sites and information published by Frontex itself. We were also able to establish the number of personnel and assets present in the operational area thanks to questions asked in the European Parliament.

According to this response, Operation Poseidon has 185 personnel, one offshore patrol vessel (OPV), eight coastal patrol boats (CPB), one coastal patrol vessel (CPV), four thermal vision vehicles (TVV) and three patrol cars.

There is also a “Rapid Border Intervention”, which contains additional assets on top of those dedicated to Operation Poseidon. This includes 74 personnel, two CPBs, two CPVs, one helicopter and three TVVs.

In total we used open sources to identify 22 assets, including vessels, helicopters and planes, which operated in the Aegean during 2020. Although this is more than the total given in the answer to parliamentary questions above, some of these assets were rotating in or out of theater.

Tracking Assets

Some assets featured regularly on the open source record. For example, Romanian and Bulgarian vessels regularly transit through the Bosphorus strait, where there is an active ship-spotting community. As such it was possible to identify their operational rotations, including vessels heading to and returning from deployments roughly every three months. However, other assets were more difficult to track, and their presence on the open source record consisted of a single image or video.

In order to track these assets and identify if they had participated in pushbacks, we required far more data than was available on social media. As such, we turned to AIS and transponder data, publicly available information about the location of particular ships or aircraft, available through sites such as Marine Traffic or Flight Radar 24.

Many of the assets we identified either did not have their information publicly listed, or appeared to only turn on their transponders under certain circumstances, such as when in port. This made them extremely difficult to track. However, some assets did have their transponders on. We began to collect this data, buying additional, more granular data from ship and flight tracking companies on dates when pushbacks had been reported.

We combined this tracking data with our own database of reported pushbacks, which we obtained through both public reports and information collected by NGOs such as Consolidated Rescue Group (CRG), Monitoring Rescue Cell (MRC) and Alarm Phone, who track these events. These included the coordinates of reported pushback events, frequently sent by the occupants of the dinghies. By overlaying these datasets we identified multiple pushback incidents in which Frontex assets were in the vicinity. Once we had identified these priority incidents we could then examine the specifics of what had happened.

Incidents

Using this data we identified six pushback incidents since March in which Frontex assets were either in the vicinity or participated directly. We have separated these into four “proximity incidents,” where Frontex assets were within five kilometers of the incident, and two “confirmed incidents,” where we can be certain that Frontex were present at the site of pushbacks themselves.

Proximity Incidents

- April 28-29: In an incident we have previously reported, a group of refugees and migrants made landfall on Samos. They claim they were then detained, placed in a life-raft without any means of propulsion and towed into the middle of the Mycale Strait. A surveillance plane overflew the area twice while this pushback took place.

- June 4: Two dinghies were reported to have been pushed back from Northern Lesbos. Portuguese vessel Nortada appears to have been present around 15 kilometers from the first incident and just over one kilometer away from the second.

- June 5: A dinghy was reported to have been pushed back from Northern Lesbos. Portuguese vessel Nortada was approximately two to three kilometers away.

- August 19: A dinghy was reported to have been pushed back from Northern Lesbos. Portuguese vessel Molivos was five kilometers away and appears to have changed course and headed towards the pushback before its transponder either lost signal or was turned off.

In these cases, Frontex assets were recorded as being within a certain range, rather than participating directly. Their exact knowledge of what was happening at these distances is difficult to confirm. Operation Poseidon’s mission includes a significant number of tasks requiring surveillance, and its assets are able to use both radar and visual tools, such as low-light or infrared cameras, to observe the environment around them.

For example, we know that the Molivos is equipped with an FLIR camera similar to this one seen on another Portuguese Frontex vessel. This model is capable of x36 magnification, with low light and infrared cameras.

The boats that migrants use to make this crossing are very basic, inflatable rubber dinghies several meters long with a single outboard motor. Due to their construction, it is unlikely that these boats would be visible on radar. However, pushbacks don’t just involve a single dinghy. By their definition they must involve at least one other vessel. From images and videos of pushbacks we have reviewed, it is clear that they often involve multiple ships from both the Greek and Turkish coast guards.

Multiple vessels, large and small can be seen surrounding this dinghy that was pushed-back on 15th August

As stated above, ships from both Greece and Turkey will frequently attempt to push the dinghies across the sea border using waves. These vessels manoeuvre in a circular pattern at a relatively high speed close to the dinghy. This manoeuvre is not only dangerous because of the risk of collision, the waves it generates also represent a threat to the overcrowded and often fragile dinghies.

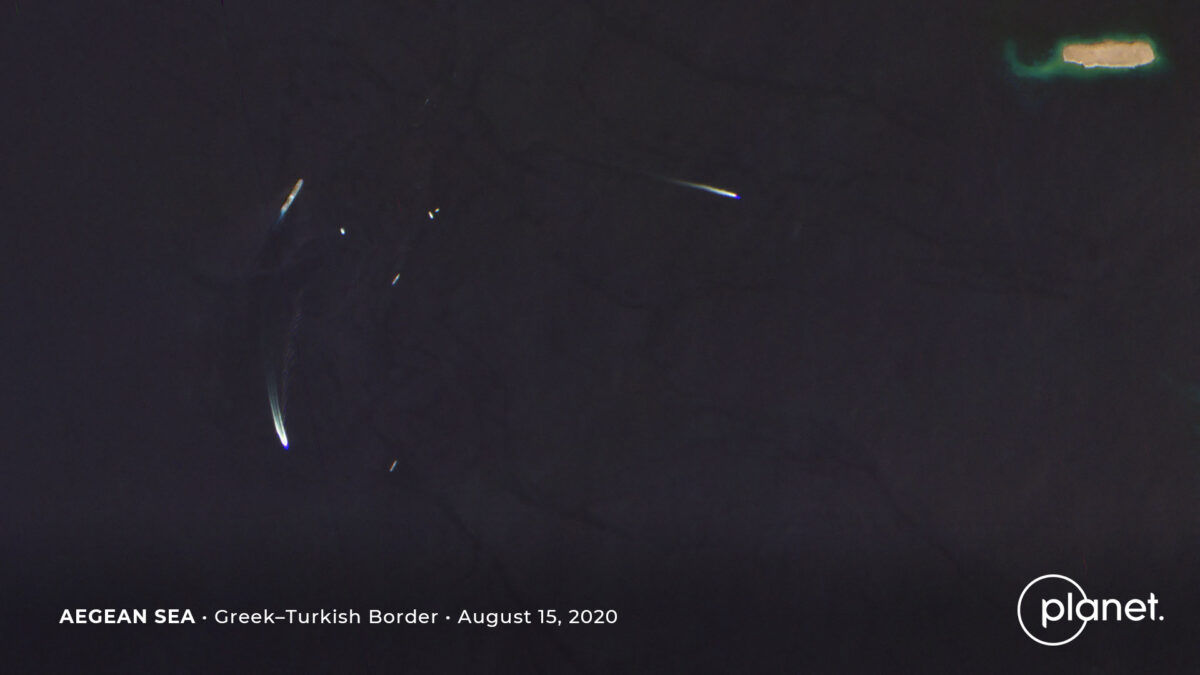

As such, although a dinghy itself may not show up on radar, the signature of a pushback would. Multiple large and small vessels from both TCG and HCG, some of which are carrying out unusual manoeuvres in order to create waves, would be very difficult to miss. Indeed you can even see this kind of event from space.

Satellite imagery from Plant Labs Inc. taken on August 15 at 11:38 AM showing the pushback in progress

There’s also the matter of visual range. The same factors that make a pushback visible on radar will also make it visible to the eye or other visual systems such as surveillance cameras. Even at a range of a few kilometers in calm seas and good conditions, a dinghy would likely be visible, although exact details such as the nature of its passengers might not be. The other aspects of pushbacks which we have already described would also certainly be visible.

The case of the April 28-29 pushback is a good illustration of surveillance assets passing very close to the results of a pushback.

April 28 – 29

In an incident previously covered by Bellingcat, a group of 22 migrants who landed on Samos on April 28 were detained by Greek law enforcement. They were then placed on a life raft without any means of propulsion and towed into the middle of the Mycale Strait by the Greek coast guard in the early morning of April 29. In response to our request for comment at the time, the Greek government denied these people had ever reached Greek territory, despite witness statements, images, and videos showing this had in fact happened.

As the life raft was floating in the strait, a private surveillance plane passed over the area twice at 5,000 feet, once at 02:41 AM and once at 03:18 AM on April 29. This plane, G-WKTH, belongs to DEA Aviation, which provides aerial surveillance services to Frontex. In a promotional video from Frontex, it is claimed these feeds are live-streamed back to the Frontex HQ in Warsaw.

The plane is reportedly equipped with an MX-15 camera, which has both low-light and infrared sensors. Considering this plane is specifically employed for aerial surveillance, it would be surprising if it did not identify the life raft full of people and, according to one member of this group, the presence of Greek and later Turkish vessels.

Indeed, the Frontex executive director’s response to the LIBE committee of the European Parliament indicates this may have been the incident Frontex reported as having seen. In this reply a “Serious Incident Report (‘SIR’) was created based on a sighting of an incident by aerial surveillance where people were transferred on a rubber boat from a vessel and later on rescued by Turkish authorities.

Active incidents

In two cases on June 8 and August 15, it seems certain that Frontex was aware of pushbacks as they took place. Indeed, on June 8, it appears that a Frontex vessel participated in a pushback, physically blocking a dinghy from reaching Greek territory.

We will first address the incident on August 15, where a Frontext vessel was present at the scene of a pushback, before examining the June 8, where a Frontex asset appears to have participated in a pushback.

August 15

On the morning of August 15 there were reports of a confrontation between the Greek and Turkish coast guards. As well as multiple photos posted to social media by locals, this was also reported as a pushback by CRG, MRC, Alarm Phone and Aegean Boat Report.

CRG and MRC also posted videos from people on this dinghy, with CRG’s video showing an engine without a starter cord, claiming it had been taken by the Greek Coast Guard. In the videos, the dinghy is surrounded by vessels from both the Greek and Turkish coast guards. We have previously noted that disabling the motor of dinghies is a tactic that has reportedly been used by the Greek Coast Guard.

Left: still image from video taken on 15th August showing starter chord has been removed. Right: where the starter cord should be on a functional engine (source)

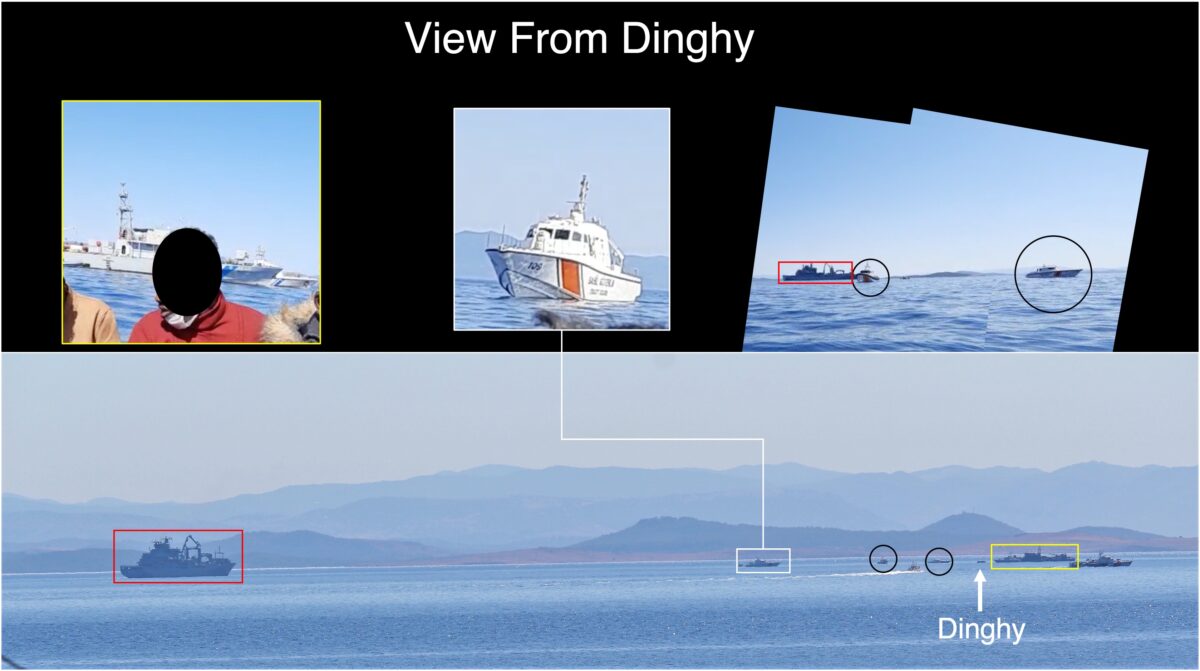

Most of the images of this incident are taken from a distance, making identification of the vessels difficult. However, we were also sent an image of this confrontation that is very clear. In this image we can clearly see the presence of MAI1102, a Romanian border forces vessel which had just arrived in theater.

Top: Image of pushback on 15th August (image provided to Bellingcat). Bottom: Comparison of vessel in image (right) with MAI1102 (left).

The metadata of this image is consistent with the date and time of this incident. Indeed, the ships can be seen arrayed in almost exactly the same manner in a video filmed by the people on the boat.

Top: stills from video taken on August 15th in dinghy. Bottom: the same ships can be seen in a very similar configuration.

Although it is not possible to be certain of exactly how far away MAI1102 is from this pushback, we can see that it is certainly within visual range of the confrontation and the dinghy itself.

June 8

On the morning of June 8 a pushback was reported to have taken place, again off the north-east coast of Lesbos. The Turkish coast guard reported it rescued 47 migrants after a pushback by the Greek Coast Guard that day. Footage published by Anadolu Agency appeared to show the Romanian Frontex vessel MAI1103 blocking a dinghy.

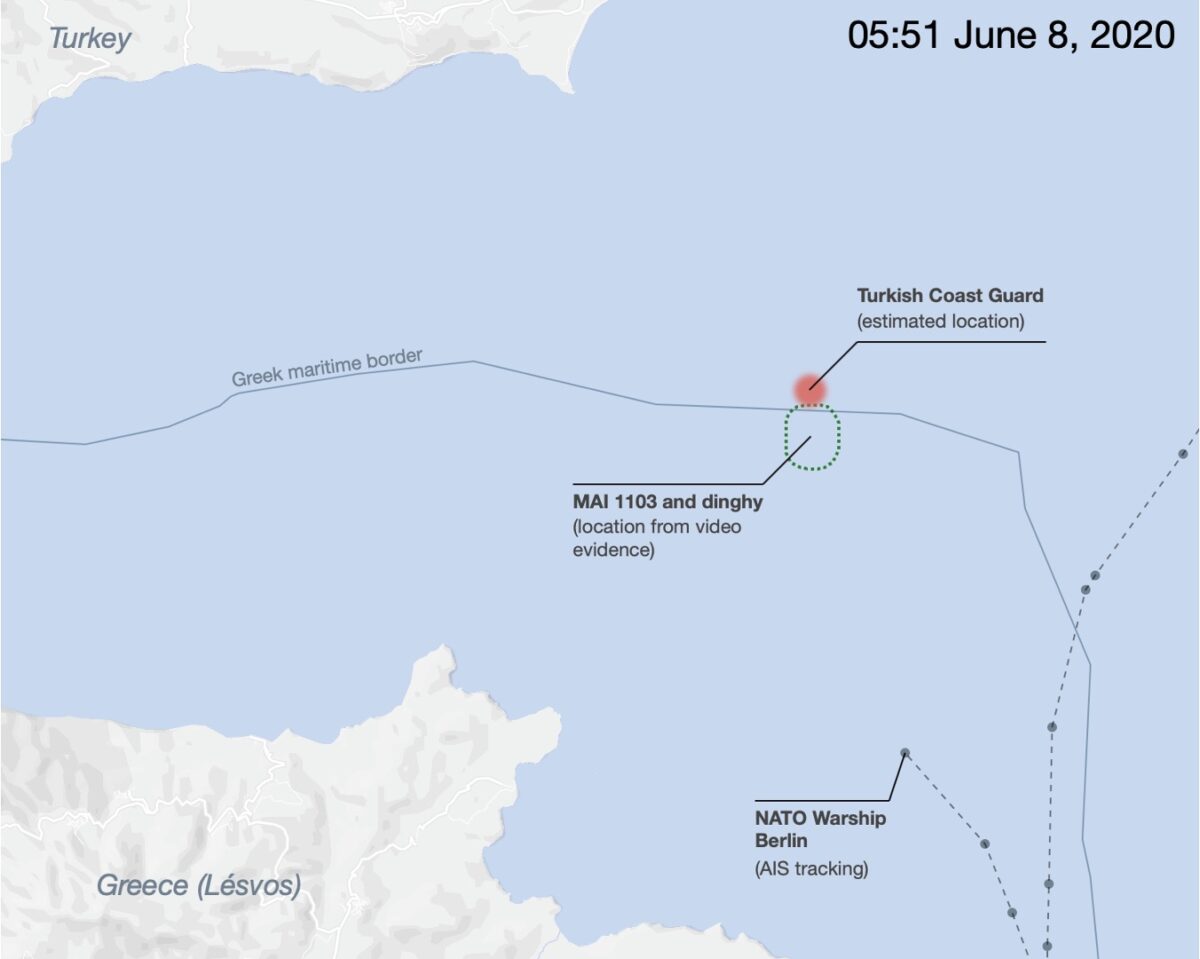

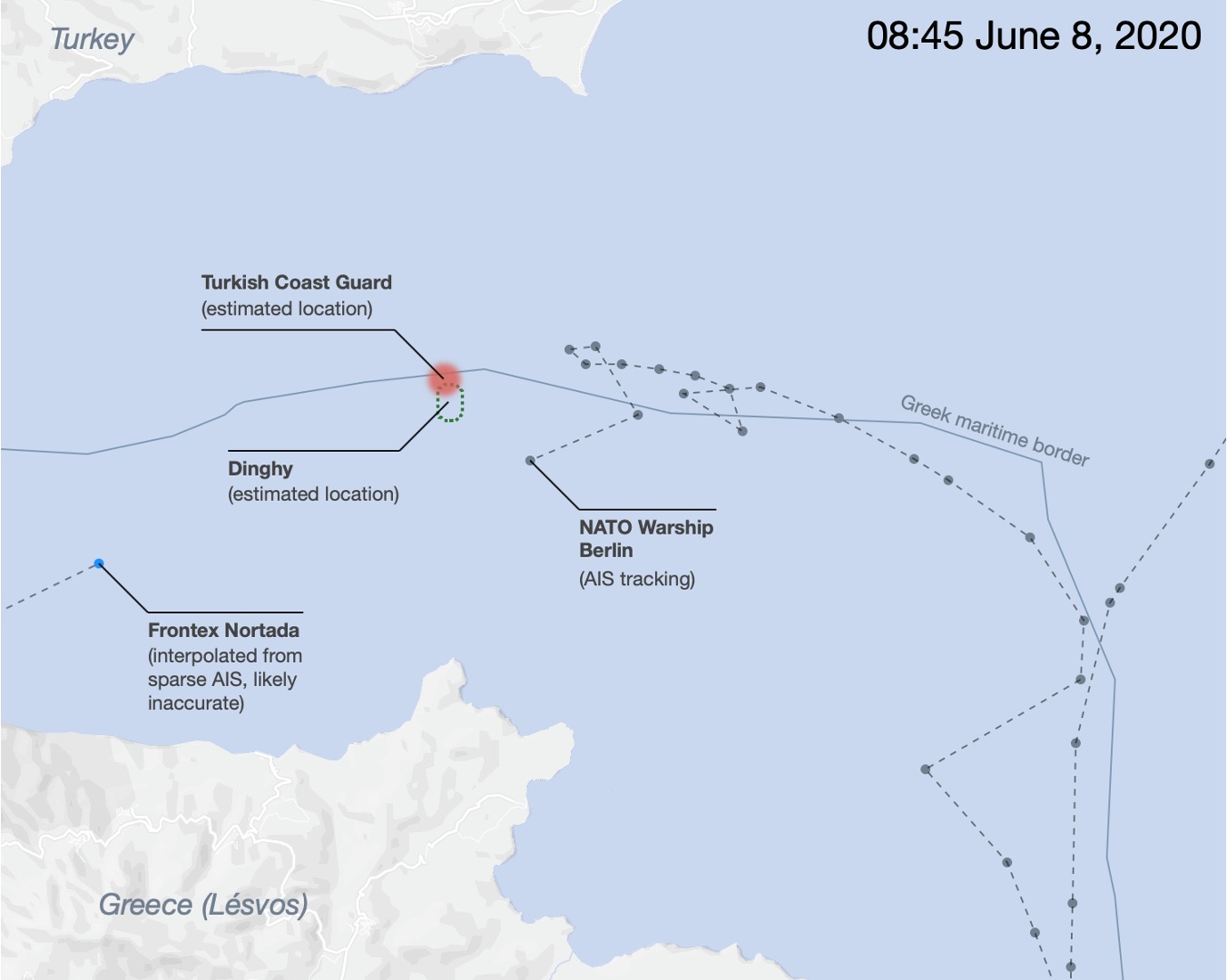

We investigated this incident further, obtaining other videos from the TCG, as well as tracking data of vessels that appeared to be in the vicinity at the time, such as the NATO ship, Berlin. Using these sources we were able to reconstruct what happened.

After initially trying to cross under the cover of darkness, the dinghy was intercepted and physically blocked from proceeding by MAI1103 early in the morning.

We can see the exact time and a set of coordinates in one of the videos we obtained.

We plotted the coordinates visible on the screen as they changed. It became clear these were not the location of the vessel with the camera, but rather the location of the dinghy and MAI1103.

We can visually confirm the general location by comparing a panoramic view that is visible in one of the videos against the appearance of the landscape from the coordinates which appear on the camera feed.

Top: panoramic of TCG video, Bottom: Landscape according to Google Earth (Credit: Google/Airbus/CNES)

We can now start to build a picture of what happened that morning.

Initial situation at 05:51 AM (credit: Logan Williams/Bellingcat, background map © Mapbox, © OpenStreetMap)

We can see that the dinghy was extremely close to MAI1103, and is being physically blocked by the ship. Indeed the two vessels are close enough that it appears that personnel on MAI1103 are communicating with people in the dinghy.

At one point MAI1103 makes a pass close to the dinghy at enough speed to generate waves, a maneuver that previously only HCG and TCG have been seen making. It is especially dangerous due to the overloaded and unseaworthy nature of the dinghies.

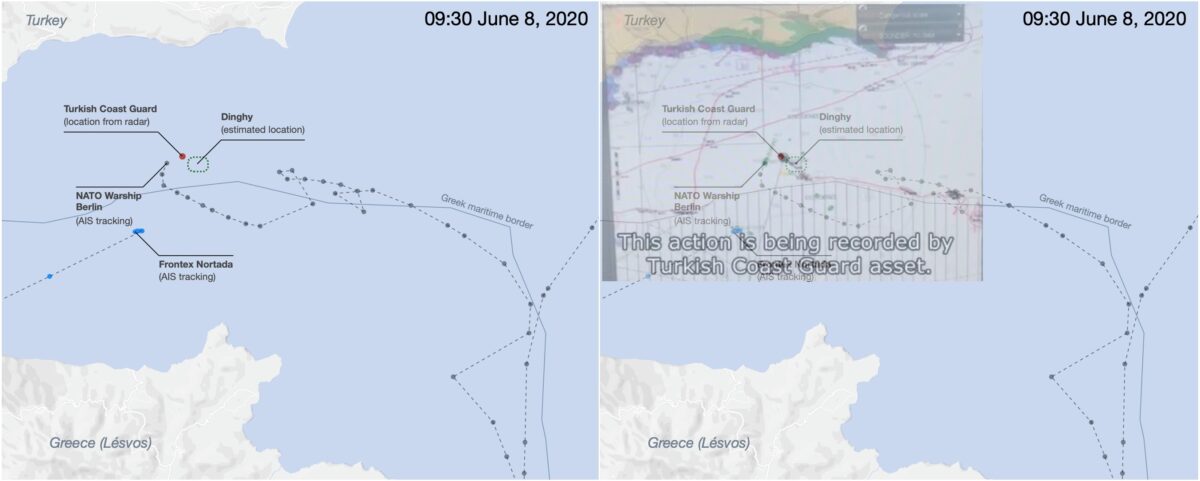

Eventually HCG vessels arrive and MAI1103 leaves, resulting in a standoff between the TCG and HCG. This lasted several hours and gradually moved to the north-west, observed by the NATO ship Berlin.

As the pushback continued, the standoff moved to the north-west (credit: Logan Williams/Bellingcat, background map © Mapbox, © OpenStreetMap)

During this period the dinghy was approached at least twice by a rigid-hulled inflatable boat 060 (RHIB) from the HCG.

In what appears to be the final segment of video taken at about 09:30 AM we see the TCG radar screen, which can be exactly matched with the Turkish coast. This radar screen matches perfectly with the location and heading of the Berlin at this time, as we can see by overlaying a plot of the Berlin’s course with the radar screen.

By 09:30 AM the dinghy appears to be dead in the water. A comparison of the radar screen and ship tracking data confirms the date (credit: Logan Williams/Bellingcat, background map © Mapbox, © OpenStreetMap)

As well as matching the movement of vessels to AIS data, we can further verify that these videos are from the same incident by examining the passengers in the dinghy. We can see that in the earliest videos, showing the MAI1103 with the dinghy, there is clearly a person wearing a white hood, alongside someone who appears to be wearing a reddish top. The presence of these passengers helps to verify that all these videos are indeed from the same incident on June 8.

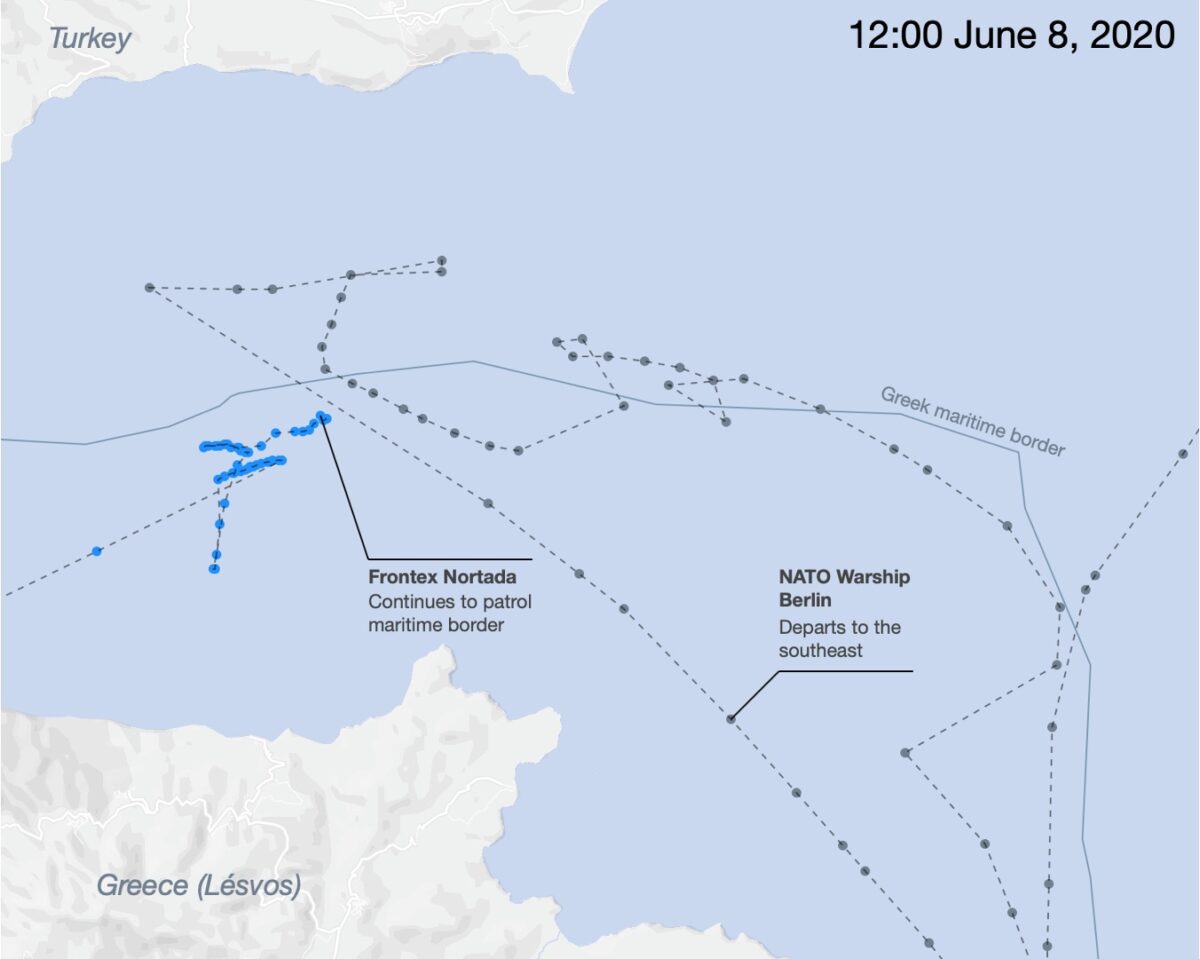

In the final stage of the pushback at 10:30 AM it is possible to see the Portuguese Frontex vessel Nortada within 5 km with both AIS data and on the TCG radar screen. The Nortada had been in that vicinity since at least 09:11 AM that morning. Although it may not have been able to pick up this dinghy on its radar, it would have certainly been within visual range of the larger ships surrounding it. After the pushback, the Nortada continued its patrol off North Lesbos.

After people had been rescued by the TCG, the Nortada continued to patrol the North coast of Lesbos, while the Berlin headed South (credit: Logan Williams/Bellingcat, background map © Mapbox, © OpenStreetMap).

Conclusion

Over the course of this investigation we collected a huge amount of information on Frontex activities in the Aegean Sea. Most of Frontex’s assets were impossible to track because their transponder information was either not registered, not turned on, or was out of range. As such, we were only able to view a snapshot of Frontex operations.

Despite this limited view, we still managed to identify multiple instances in which Frontex was either present at pushbacks, or close enough to be able to understand what was taking place. In at least one incident it appears that a Frontex vessel actively participated in a pushback. It is possible that there are other incidents we have not been able to capture.

In a statement provided in response to this investigation, Frontex stated that it applies “the highest standards of border control to its operations” and that its officers are bound by a code of conduct that looks to prevent refoulement and to uphold human rights.

The statement continued that Frontex’s executive director had notified the HGC regarding all reported incidents and that Greek authorities confirmed that an internal inquiry had been launched.

A spokesperson for the Greek Maritime Ministry said the actions of HCG officers were “carried out in full compliance with the country’s international obligations, in particular the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, the International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea and the International Convention on Maritime Search and Rescue.”

The spokesperson added that thousands of migrants had been rescued throughout the refugee crisis of recent years by the HCG, that allegations of illegality were “tendentious” and that the “operation practices of the Greek authorities have never included such [illegal] actions.”

This investigation is part of the Borders Newsroom at Lighthouse Reports. The production was supported by a grant from the Investigative Journalism for Europe (IJ4EU) fund.

Editor’s note: This article was updated to further clarify that the April 28 – 29 incidents happened over two days, beginning on April 28 and continuing into the morning hours of April 29.