Migrants From Another World: Introduction To The Project

Every year, thousands of people expelled from Asian and African countries cross Latin America looking for the north like swallows disoriented by an altered climate. Along the way, the already painful journey of these extraordinary human beings is made unnecessarily difficult by almost all governments — putting people at constant risk. This is an introduction to a collaborative, cross-border investigation that tells the story of their passage through our countries.

I met Kamal on the morning of January 16, 2020 in Necoclí, a village populated by poor fishermen, on the edge of the rough green sea of the Gulf of Urabá, in the north-western corner of Colombia. Kamal was fleeing Dhaka, Bangladesh, after religious extremists burned down his tea shop. His country has a Sunni Muslim majority, and, like the rest of the region, it has been affected by the ravages of global terrorism and the war against it, as well as by sectarian demagogy of leaders in both hemispheres. These factors have led to criminal attacks on the homes, businesses, and temples of Hindu, Buddhist, Muslim and Christian minorities.

Every year, half a million Bangladeshis are forced to leave their country. Those exiled by violence, like Kamal, are joined by those displaced due to climate change, which has especially affected Bangladesh, which is dealing with rising sea levels and overpopulation; increasingly frequent floods and landslides literally sweep the land from under the citizens’ feet.

Like most migrants, many Bangladeshis take refuge in neighbouring countries, seeking to rebuild their lives not too far away from their home regions. Many, however, decide to leave for the Americas. Between 2017 and January 2019, 1,608 Bangladeshis requested refuge in Brazil.

Kamal, too, flew to Sao Paulo, but connected directly to Bolivia and there began his journey northwards, overland. That’s where he was headed when we talked to him in Necoclí. Throughout 2019, Bangladeshis were in the top five list of people from Africa and Asia who took this route to the United States or Canada. Seven hundred and three travelers with a Bangladesh passport were registered by Colombian migration points, and, officially, 1,561 were presented to migration authorities in Mexico.

The forces of globalization that now shape our lives — via transnational economies, multinational militias, remotely ordered bombings, climate change, the internet — have turned on the taps of migration across the planet. There are 50 million more migrants today than there were ten years ago, and the percentage of people living in a country other than their native one has been increasing.

This cross-border investigative collaboration, involving 18 media organisations in 14 countries, uncovers an intense and little-known chapter of the modern history of global migration.

We called it “Migrants From Another World” because the project tells the stories of people who travel between five and ten thousand miles to the opposite side of the planet. Once in the Americas, they cross the continent in express buses or planes, in speedboats or rafts, in clandestine taxis or private cars taking hidden routes and tricky shortcuts, always towards the north, to the United States or Canada, like stunned swallows. Often, they cross entire stretches relying only on their legs.

They are Migrants From Another World because the moment they set foot on the continent, their Bengali, Lingala or Hausa, Fula, Hindi or Nepalese, Arabic, Urdu or Sinhalese loses all their value, and not even French, Portuguese or English are of any use to them in the deepest villages, where no one understands them.

They are from another world because their courage and conviction are extraordinary. Determined to make a new life for themselves and, often, to open paths for those they leave behind, they take on the exploitation of swindlers on the road, the hostility of migrant posts and local corruption, they endure assault and rape, hunger, fear and threats, imprisonment and death.

“Death is also a form of freedom,” says my colleague Juan Arturo Gómez, a member of this journalistic team who lives in the Gulf of Urabá region, very close to the border with Panama. He heard the phrase from an immigrant, and it stuck with him.

Why Such A Long Journey?

There are many reasons why migrants take this particular route, which seems absurdly long. One often mentioned by African migrants is that the road to Europe via Libya, where they torture and enslave travelers, terrifies them. Another is that the United States offers fewer and fewer quotas for refugees, which had previously made it possible to wait patiently at home or in a friendly country until they were allowed to fly safely and directly.

The Trump administration has narrowed refugee quotas (reducing the 110,000 planned by the Obama administration for 2017 to 18,000 this year, now reduced to zero due to the novel coronavirus). This left migrants and refugees with no choice but to attempt a tortuous route that can take months, enter illegally, and beg for asylum once inside. It’s the case of the 1,327 Indians who were granted asylum in the United States in 2018, the last year for which the government provides figures.

Moreover, with instant global communication, no place seems so distant, no journey seems so lonely. On phones and in internet cafés, migrants follow the digital crumbs left behind by their fellow countrymen. Relatives and friends extend a helping hand, sometimes paying for the trip. Other times, the travelers pay for it themselves by borrowing from their families, selling whatever goods they have — like Kamal, who sold his land — or getting in debt with their future as sole guarantee of repayment.

Migrants have Facebook and WhatsApp on their phones, and they can report what happens to them along the way. They span networks by nationality, like the one Malians and Senegalese have been building in Brazil and Argentina since the late 1990s. In chat groups, those who have already made it through put them in contact with some migrant protectors — like Luis Guerrero Araya, whom I met in La Cruz, Costa Rica — and they can let others know if there are problems ahead.

Once some find soil to put down roots, they call the others, and those call others. This is what humanity has always done: migrate in clusters.

This long journey is also possible because, although migrants are unwelcome almost everywhere, their money is always welcomed. It flows easily from accounts in Karachi, Pakistan and Douala, Cameroon to Cruzeiro Oeste and Sao Paulo, Brasil or to Apartadó, Colombia, it crosses all borders with very little paperwork, through multiple international instant money transfer services like Western Union or MoneyGram, which are often mentioned.

This is what this journalistic alliance heard from many migrants in different parts of the American geography, as well as from the official sources, academics and activists who spoke to us.

Over 40 journalists and editors and translators, videographers and photographers, producers and creators, programmers and developers, designers and artists built Migrants From Another World. We were united by one purpose: to render these migrants in flesh and blood after they have been made almost invisible to the world. Even in the annual reports of the International Organization for Migration (IOM), they barely show up.

Their stories are only printed when tragedies happen or, worse, when the perpetrators are the sole subject. In this nine-month investigation, however, we followed their stories from beginning to end. We wanted to hear from those who managed to settle in the north and ask them whether it was worth the cost; we wanted to find out what happened to those deported or imprisoned, to put a face and a name to those who died and whose remains lie in unknown places or mass graves by the roadside.

Our hope is that after browsing through the five chapters of Migrants From Another World more people will know that these migrants exist, and that more will hear their only plea: a safe and dignified passage through the continent.

How Many Migrants Are There & Where Do They Come From?

Because of the clandestine nature of most journeys, it is impossible to specify the exact number of migrants from Asia and Africa who pass through Latin America each year on their way to the United States or Canada. However, crossing-referencing the data of each country, we come to a figure that oscillates between 13,000 and 24,000 people.

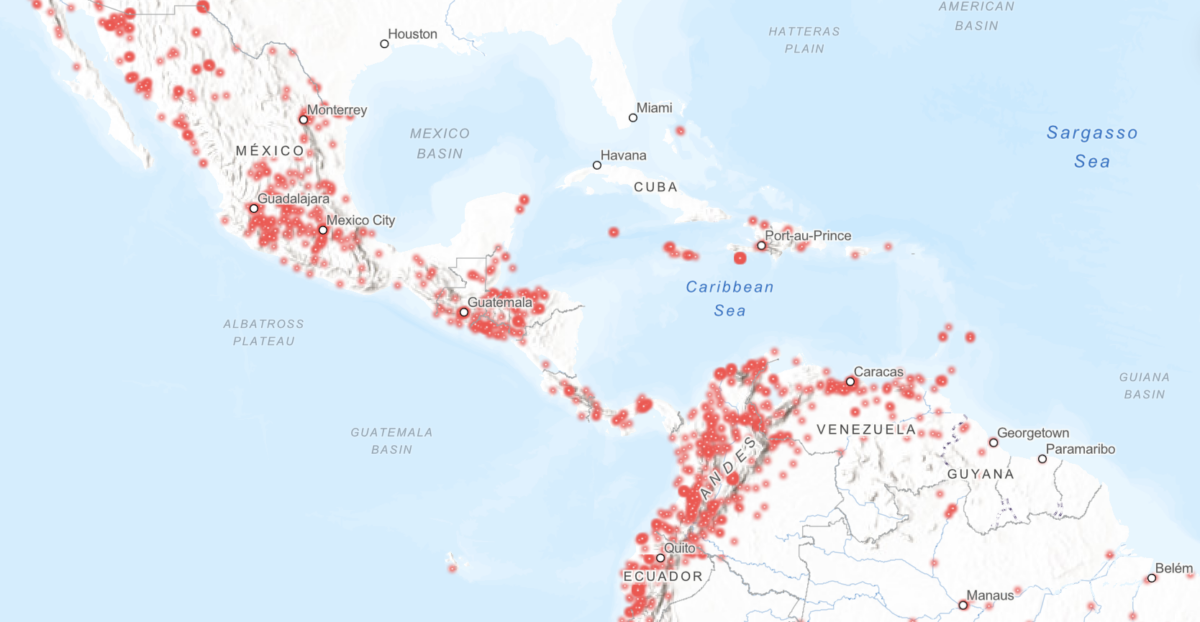

In the animated map above, the main routes of the first transatlantic leg of their voyage are traced. We put together this map of routes based on studies by experts, judicial records and reports published by other media, but above all it is based on the stories of the transcontinental travellers themselves.

Sometimes accompanied by their children, they board flights from New Delhi in India and connect in Abu Dhabi or Dubai in the Arab Emirates; or fly from Addis Ababa in Ethiopia, or Casablanca in Morocco, or Lagos in Nigeria, or Johannesburg in South Africa, or even Moscow in Russia. They land at airports in Sao Paulo where they can get off or connect to Quito or Panama. They can also arrive in Buenos Aires, Caracas or Havana. Others try their luck at the African seaports of Durban or Port Elisabeth, Freeport, Lagos, Malabo, or Pointe-Noire, where they climb aboard ships, sometimes stowed away, and other times on cargo ships or barges that can barely cross the Atlantic. They land in the port of Santos, near Sao Paulo, or in the port of Buenos Aires, or are rescued in Maranhão, Brazil.

Having reached the Americas, they face the most difficult stretch of the voyage, as is told in chapter two, Routes through the Americas.

We gathered the most recent official figures available from the countries that witness more transit, but migration authorities do not always collect identical statistics and it is difficult for the number of migrants of one nationality registered in Panama, for example, to coincide exactly with those of neighbouring Costa Rica. There is clandestine transit that goes through the tightest borders unnoticed and constantly changes course in order to avoid detection.

Overall, however, the figures do establish that the transcontinental migrants who used this route the most throughout 2019 had passports from Cameroon, India, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Bangladesh, Angola, Sri Lanka, Eritrea, Nepal, Pakistan, Ghana, Guinea and Mauritania. We also discovered that many of them arrive first in Brazil, a country that for some years welcomed international immigration. Between January 2018 and January 2019, Brazil gave refuge to 27, 760 foreigners from 53 nationalities. Among them 270 from the DRC.

After a while, many migrants abandon hope of receiving refugee status. As Profissão Réporter of TV Globo, another partner in this investigation, found out, thousands land in poor neighbourhoods on the outskirts of Sao Paulo, live in slums or else occupy abandoned buildings in appalling conditions, and cannot find decent work. After two or three unsuccessful years trying to settle in Brazil, they continue their journey north. This was the case of Angolans and people from the DRC we encountered on the trail up north. Many also are denied their refugee permits, like Bangladeshis, Pakistanis and Ghanaians.

Immigrants of other nationalities, such as those from the Sri Lanka, do not appear to have begun their journeys through Brazil. Only 39 people of this nationality asked for refuge there between 2017 and March 2019. But in Ecuador, according to 2019 migration registries, a number over ten times this size left without checking their passports with migration authorities, indicating the clandestine nature of their trip. In Costa Rica, migration authorities recorded the arrival of 738.

Migration posts are likely to mistake countries with similar names – like DRC citizens for Congolese people, to give one example — and this may partly explain some inconsistencies in the data. It also means that by passing through more remote crossings, the migrants manage to avoid detection. An interactive map in this chapter reveals other similar cases: in Colombia, for example, only 103 Eritreans received safe passage, while Mexican migration registered almost a fourfold increase.

Often, the migrants do not reach their destination. This was the case of Sanjiv, Raja and Harpreet, who were born in India and whose story we told in partnership with The Confluence, an Indian news outlet. In Mexico, already in the last stretch, they were caught by the authorities along with 308 of their fellow travellers. After being locked up, they were put on a plane back to New Delhi. You will also find here the story of the Van Dung Nguye, from Vietnman, who was lost in the labyrinth of a broken justice system in El Salvador.

Journalist and DRC native Josep Pele, who also collaborated with this alliance, did manage to reach the United States accompanied by his family, but found his options frustrating: a waiting period of a year to find out whether they would give him refuge or not, without a work permit. He set out to Canada, where he now lives. The project documents his difficult journey. Another subject of the project, Colette, originally from Cameroon, is already on the other side, in Odenton, Maryland, with her daughters. The American dream, however, was sadder than she had imagined, as we discuss in the project.

On the road, a reporter from this alliance found a wall in a makeshift shelter for migrants in Colombia’s Chocó region inscribed with messages and signatures left by migrants as testimony to their passage. We started searching for some of the authors. That is how we found Ramesh, from Nepal, who had written his message in 2015. With the help of a reporter in Nepal, our project reconstructed his story.

What Are The Journeys Like?

There are many Forbidden Passages (Chapter 3) in this extremely long journey in which almost all governments set hurdles.

The crossing of the Darién jungle between Colombia and Panama, to which we dedicate a mini-documentary, is the route that no one forgets. There is the sticky heat, the hills of death, and the smell of bodies rotting in the mud. There, some people lose everything, including their lives: some have had to leave their children behind.

The journey does not end there. When they reach the Pan-American Highway in Panama, already in civilized territory, migrants are given a boost, as both this country and the next one, Costa Rica, facilitate their passage with fast and safe transportation. Very soon, however, they arrive in Nicaragua, famous for lawlessness toward its own citizens, much less for foreigners. There, migrants must pay their way, and they don’t always make it out unscathed. We relate the experience of migrants who cross this clandestine path.

We also tell about the following leg of the journey: the diagonal crossing of the Honduran territory, from Choluteca in the south, near the border with Nicaragua, to the lonely border with Guatemala, in Agua Caliente. From this point onwards, Asian and African migrants will no longer venture out in daylight until they reach Mexico. Once they have crossed the border, they have to wait in a camp in Tapachula. Due to a sudden change in the application regulations, thousands of people became stuck there last October. Sleeping in tents in front of the migration station, the situation soon became explosive, as our partners who stayed there twice during the investigation, tell in yet another story.

Those Who Never Arrive

Migrants frequently die or go missing en route. In many cases, this happens because the governments of various countries believe that by closing borders or else by preventing migrants from passing through safely, officials can then make migrants give up. If these officials truly understood migrants, they would know that the forces that drive them are not limited to their individual will, but belong to the times we live in and are affected by hunger, poverty, death, and war. Officials fail to see that when a person deems their country’s situation hopeless, they have no other choice but to move on.

Rarely do governments pay a political cost for the mistreatment of these migrants. In Colombia, it took a major shipwreck like the one in January 2019, in which 21 migrants drowned, for the government to loosen its immigration rules again. Now, as travellers have told us, Colombia allows migrants five days to cross 1,200 kilometres of its territory. In Mexico, the agreement signed with the United States to reduce the flow of foreigners trying to reach the north is applauded by most of its citizens. A sad paradox, surely: a country of migrants proudly policing other migrants to keep them from reaching their goal.

Migrants From Another World counted 110 people of various nationalities suspected of having died or gone missing on the border between Colombia and Panama. Some drowned in sudden rises of the unpredictable jungle rivers, or in the sea; some died of heart attacks because of the enormous toll exacted by the journey; some were murdered. Of some individuals’ fates, nothing is known. Many do not appear in the official statistics of any country. Even the impressive database recently built by the IOM’s Missing Migrants Project accounts but for a fraction of them.

In chapter four, The Fallen, we map the trail of death and disappearance left along the routes pursued by migrants of all nationalities, documented by us and IOM between 2016 and February 2020.

Among the dead are the 21 people who were shipwrecked and today lie buried as anonymous victims in Acandí, a fishing village on the Gulf of Urabá, in Colombia. We found out how these people ended up there and who they were. Victor, a project subject from Cameroon, was also left behind on that infamous border — and as part of our project, we tracked down his family in the United States.

In addition, in partnership with The Museba Project of Cameroon, we tell the story of four Cameroonians who drowned in 2019 in the sea off the coast of Tonalá in Chiapas, Mexico. We relate the pain of family members who put their faith in the future of a loved only to welcome him back in a coffin.

A Bitter Reality

Despite having been subjected to a process of economic “denationalization”, as sociologist Saskia Sassen has argued, countries around the world have also undergone a parallel process of “renationalization”. This can be expressed in the detention of migrants as a way of exercising control over territory, often in contradiction with the very international treaties in which governments have committed to giving refuge or asylum to those fleeing from war, or to treat economic migrants humanely.

In the Americas, this contradiction has resulted in an erratic legislative map that greatly favours human trafficking, which is the other cruel face of migration. Not all migrants cross the ocean led by peers or family members. Necessity easily leads many of them into the hands of traffickers who know how to take advantage of the opening and closing of borders in order to turn a profit.

Fluid relations within their mafias allow traffickers to constantly trace new routes for their human cargo. They adapt quickly, coordinate with each other using instant messaging, and compartmentalize payments and information, which they give to migrants on a need-to-know basis. Trapped in their clutches, migrants have no choice but to drain their resources and those of family members and acquaintances. That’s because when it comes to the flow of money, there are no borders, of course.

There is ample evidence that the main promoters of trafficking are not “lax” governments, as immigration authorities like to call nations that try to be in tune with globalization, but governments that decide to shut their borders and pretend as if migration is simply not happening.

As we show in A Cruel Business, the fifth chapter of Migrants From Another World, border restrictions and a growing market of travelers make prices go up, keeping the trafficking business afloat. The stories in this chapter reveal how these criminal networks and their various rings of power operate: From elites who charge thousands of dollars in advance and coordinate payments between big cities, all the way to corrupt local authorities who take their share, as well as to expiatory “coyotes”.

For example, we tell the story of a hotel owner who began doing favours to migrants near a particular border and ended up as a pawn on the large chessboard that is the game of trafficking. We profile other characters as well.

There are some aspects of migration/trafficking that authorities know better, such as the legal arrival and clandestine departure from Ecuador — something we documented using legal cases — and there are also the more shadowy aspects, the outlines of which we have drawn in Venezuela.

We must also note that local police can confuse migratory networks of friends and acquaintances with commercial trafficking networks — and end up punishing good Samaritans instead of criminals in the process. We reported on one such case, involving three Senegalese people in Argentina.

How The Pandemic Affects Migration

Today, as the coronavirus leaves a trail of death around the world, countries have closed their doors to prevent contagion. The status of migrants who travel precariously, sometimes without documents and without money, is now especially critical.

Some are locked up in detention centers such as Otay Mesa in San Diego, California, waiting for a judge to consider their request for asylum. Now they will have to wait, with the risk that U.S. President Donald Trump — whose immigration policies appear to stem from pure xenophobia — will extend the suspension of asylums beyond the duration of the pandemic.

Maxcello, a Cameroonian shipwreck survivor from Tonalá, Mexico, whose story we tell as part of the project, was held in Otay Mesa until mid May. It has already been announced that there are at least 41 people there infected with COVID-19.

Mexicans and Central Americans who are arriving at the border during quarantine are deported to Mexico, not knowing whether they are infected or not. It is Mexico that has taken it upon itself to return them to their countries or to abandon them in the south to find their way back for themselves, regardless of what happens to them — and regardless of what they were escaping from.

In addition, the United States maintains its usual expulsions from detention centers without proper health controls. A Mexican returnee from Houston, Texas, arrived sick at a migrants’ shelter in Nuevo Laredo and has already infected others. Dozens of deportees in Guatemala arrived with the virus, causing a general rejection of new arrivals.

Many travelers from Asia and Africa who are just arriving in the United States are apparently being sent back to their countries of origin. Those who were halfway there when the countries ordered quarantine were trapped in shelters or in border towns, exceeding the numbers these can receive under minimal humanitarian conditions.

In Necoclí, the same town in the northern corner of South America where I spoke with Kamal last January, 294 people, 14 of them Africans, had to be accommodated two months later, overwhelming the capacity of the local mayor’s office.

Coronavirus, which has been fueled by global phenomena such as climate change and economic globalization, has revealed the great contradictions in current migration policies and the damage they cause to those expelled by the exact same phenomena.

In a world where everything circulates unhindered, except for individuals fleeing for their lives, ambiguity and whim when it comes to closing borders and the sudden suspension of the migrants’ and refugees’ rights are crimes of omission. By hiding behind dubious national policies under the pretext of protecting their citizens, governments are contributing to a global crisis, turning their backs on the people who exemplify the human capacity to dream of a better tomorrow.

Migrants from another World, is a cross-border investigative journalism collaboration by the Centro Latinoamericano de Investigación Periodística (CLIP), Occrp; Animal Político (Mexico) and the Mexican regional media Chiapas Paralelo and Voz Alterna, from the network Periodistas de a Pie; Univisión Digital News (United States), Revista Factum (El Salvador); La Voz de Guanacaste (CostaRica); Profissão Réporter deTV Globo (Brazil); La Prensa (Panama); Revista Semana (Colombia); El Universo (Ecuador); Efecto Cocuyo (Venezuela); and Anfibia/Cosecha Roja (Argentina) in Latin America. Other collaborators in the investigation were The Confluence (India), Record Nepal (Nepal), The Museba Project (Cameroon) and Bellingcat (United Kingdom). This project received special support from the Fundación Avina and the Seattle International Foundation.

This is the English version of an introduction to this project that was originally published in Spanish on May 28, 2020.

The Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP) has also published a set of materials, in English, as part of the “Migrants from Another World” project. You can find those materials on the OCCRP website.