Nine Years of War — Documenting Syrian Arab Army's Armored Vehicles Losses

Over the course of nine years of war, the Syrian Arab Army (SAA) has engaged in armed conflict against various opposition forces composed of domestic rebels and foreign volunteers, often equipped with light weapons.

Given the sheer amount of open source information available related to these events, it is possible to track the military vehicle losses of the SAA — an army that once had the 6th largest number of tanks in the world. The numbers used in this article have been updated in late March 2020.

Before outlining the armored tracked vehicle losses that can be confirmed by visual evidence (photos and videos), the methodology of collecting the information will be examined. The article ends with a discussion on the reasons why the SAA may have lost so many armored tracked vehicles.

A T-72 AV Soviet second-generation main battle tank of the Syrian Arab Army near the border with Israel. Date unknown.

General Information on the SAA’s Armoured Vehicles

To understand the context of the armored tracked vehicle losses in the Syrian Civil War, it is important to briefly discuss the pre-war history of the SAA.

For decades, the SAA had two main tasks. Firstly, the SAA needed to provide internal security for the Assad government. Secondly, the army needed to be able to conduct both offensive and defensive warfare against the State of Israel.

It was the latter task that arguably most influenced the aspects of the SAA, and focused heavily on obtaining large numbers of tanks, armored personnel carriers (APCs), and infantry anti-tank weapons (mostly former Soviet RPGs and anti-tank guided missiles). Due to the fear of an Israeli attack, the SAA’s arsenal was spread over a large number of military bases across Syria’s governorates. A disproportionate number of those bases were established in the Damascus and Daraa governorates, which are situated close to the Golan Heights which have been occupied by Israel since the 1967 Six-Day War. For more information, the “The Syrian Army: Doctrinal Order of Battle” report by the Institute for the Study of War is an excellent report.

At the start of the Syrian Civil War in 2011, the SAA had on paper approximately the following number of armored tracked vehicles:

- Tanks

T-55: 2 000

T-62: 1 000

T-72: 1 500 - Armoured Personnel Carriers

BMP-1: 2 000

BMP-2: 100 - Support Armoured Vehicles

BVP-1 AMB-S: 100

ZSU-23-4 “Shilka”: 400

armored recovery vehicles: 130 - Self-Propelled Artillery

2S1 Gvozdika: 300

2S3 Akatsiya: 100

Note: The numbers of pre-war SAA armored tracked vehicles should be regarded as optimistic estimates. Some armored vehicles were lost in past decades without being accounted for, while many others were not operational (or even beyond repair) at the start of the Syrian Civil War due to being in long-term storage with minimal or no maintenance. Given these factors, more realistic initial numbers would be about 33% lower than what is listed above.

Later, the SAA obtained dozens of MT-LB APCs and T-90 tanks from the Russian Federation. The T-90s were first supplied in late 2015.

Source Tanks Encyclopedia. Composite image first posted by @WorldOnAlert.

On paper, the SAA also has other types of armored vehicles: the BTR series of APCS, the T-34/D-30 self-propelled artillery, and other armored tracked vehicles. However, they are generally extremely obsolete and therefore with minimal combat value; most of them are likely to have been scrapped or retired from service many years ago – at best some might still be parked at checkpoints in Syrian government controlled areas. This article is therefore limited to the types of vehicles that are actively being used by the SAA in the Syrian Civil War.

Collecting Visual Evidence

As most of Bellingcat’s readers are likely aware, YouTube and other video and photo hosting websites have been deleting much footage related to the Syrian Civil War, this as part of their effort to show that they are fighting extremist material on their servers. Between false positives and malicious use of reporting content by supporters of all sides of the Syrian Civil War, this has resulted in many photos and videos being lost forever.

Nevertheless, YouTube is still the main source of visual evidence that has been collected for this database. The author has archived footage from the Syrian Civil War since Spring 2015, mostly focused on documenting rebel ATGM use.

Another important source information has been the Lost Armour website, which is easy to use and sort data though many of its source links refer to dead YouTube links. However, some Syrian government armor losses are missing on the website.

All of this and other sources have resulted in an archive worth of 144 gigabytes of data in 5 801 files, 90+% of which are videos with the combined length exceeding 100 hours of war footage.

As mentioned above, this article only includes losses for which there is visual evidence. For that reason, there may be losses that are not counted due to vehicles that could not be identified.

The term ‘losses’ refer to both heavily damaged and destroyed vehicles, and also to captured vehicles.

In case footage did not have enough detail to reliably determine the exact type of tank, it is referred to as an “unknown type of tank“.

Since the SAA operates only a relatively small number of BMP-2s and BVP-1 AMB-S (the SAA had around 100 of each before the Syrian Civil War started) and BMP-2s rarely appear outside of Damascus governorate, they have been counted as a BMP-1 unless there was a positive ID for a BMP vehicle.

Several measures have been taken to avoid double counting, such as comparing footage of captured military bases and counting vehicles that were captured or destroyed operated by opposition forces, the so-called Islamic State (IS) or the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF).

Since the SAA rarely captures intact armored vehicles from its enemies, tracking such incidents has not been included. It is also a difficult task to gain further information about the SAA vehicles that were repaired. The number is likely to be relatively low since satellite photos of the army’s main facility for overhaul or major repair of armored vehicles show little to no activity.

Having discussed the methodology, the SAA’s vehicle losses will now be presented and discussed per year.

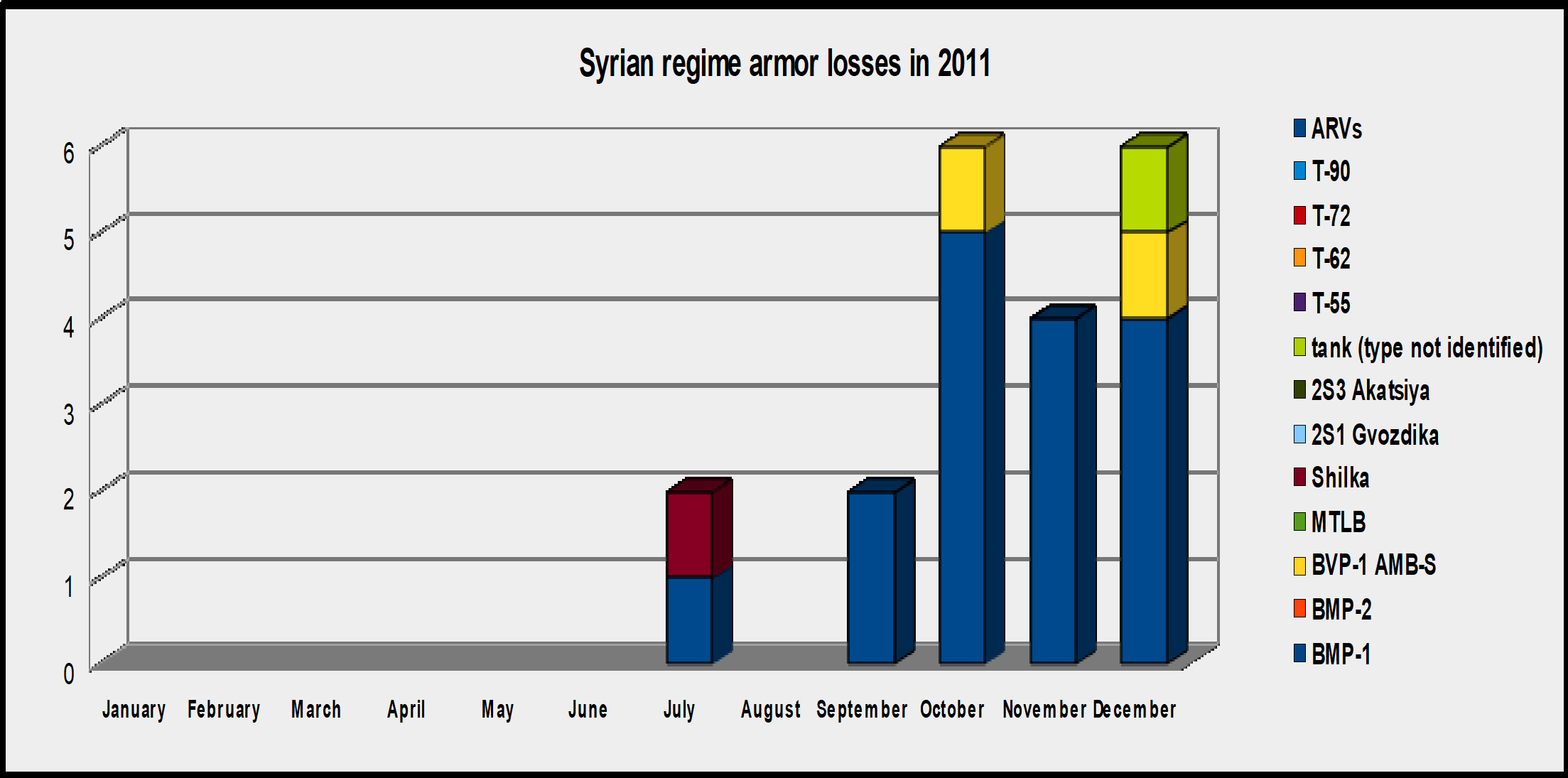

Armor Losses in 2011

During the first months of the Syrian uprising, the heavy violence was mostly one-sided, namely coming from the Syrian government shooting at protestors. Gradually, however, due to army defectors getting organized in armed resistance, they started targeting — and destroying — less protected armored vehicles, mostly BMP-1s.

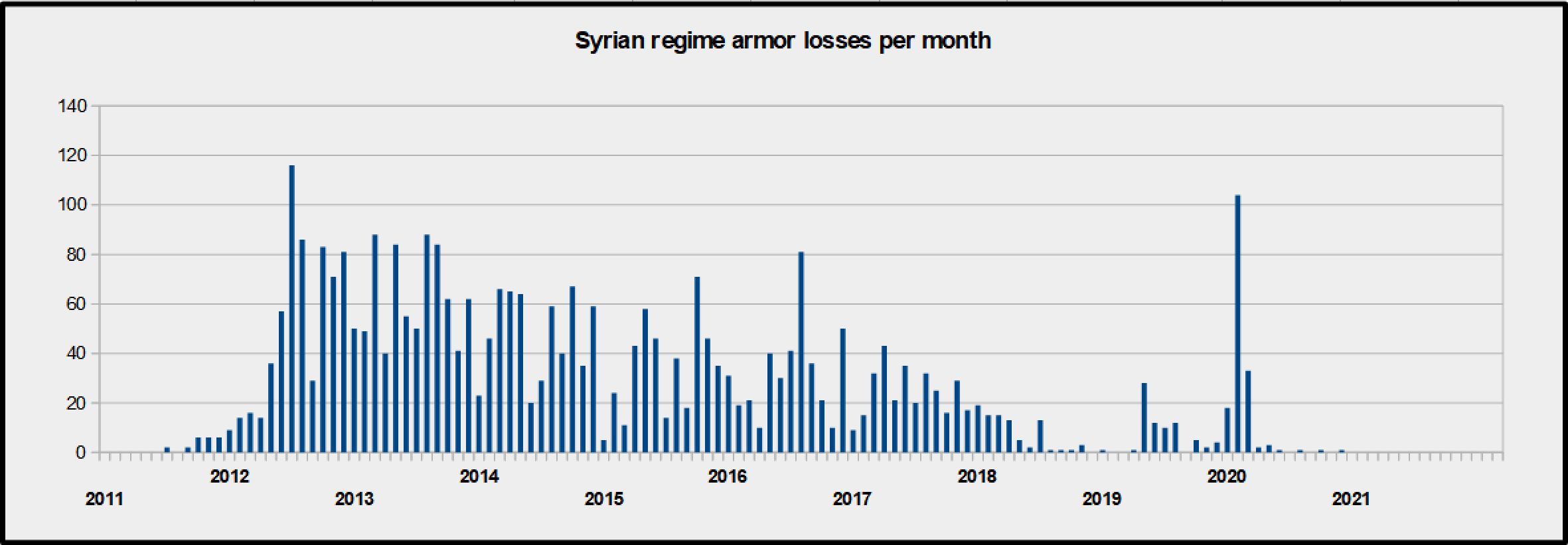

In 2011, a total of 22 armored vehicles of the SAA were lost.

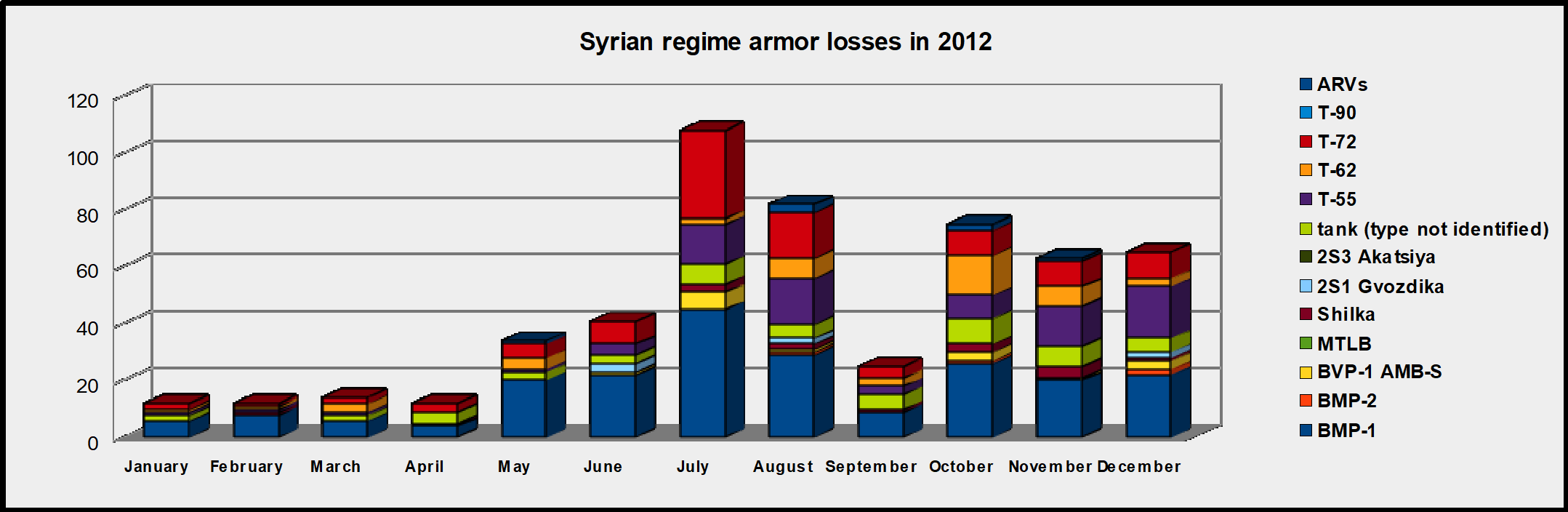

Armor Losses in 2012

In 2012, there was a lot of effort to stop the fighting which resulted in a ceasefire. Although the truce did not hold in many places, it did reduce overall violence and therefore also a lull in SAA armor losses. This period of relative calm lasted until early May 2012 when Bayda and Baniyas massacres happened, at which point opposition forces decided to abandon the ceasefire and started series of well-planned attacks at regime positions, which resulted in a massive increase in losses of armored vehicles to staggering 109 in July and 82 in August.

Reason for such a high rate of losses despite the fact that rebels were only lightly armed (main weapons against armored vehicles were RPGs and IEDs and/or mines) was a combination of poor tacts of the SAA, rebels making significant preparations for attacks on vulnerable points during the ceasefire and fact that at that time frontlines were in most places not yet established — giving rebels element of surprise in most attacks. As a result, the Syrian government gave up some of the indefensible territories which in turn helped reduce losses to “only” 30-50 per month.

In 2012, a total of 612 armored vehicle losses of the SAA were documented.

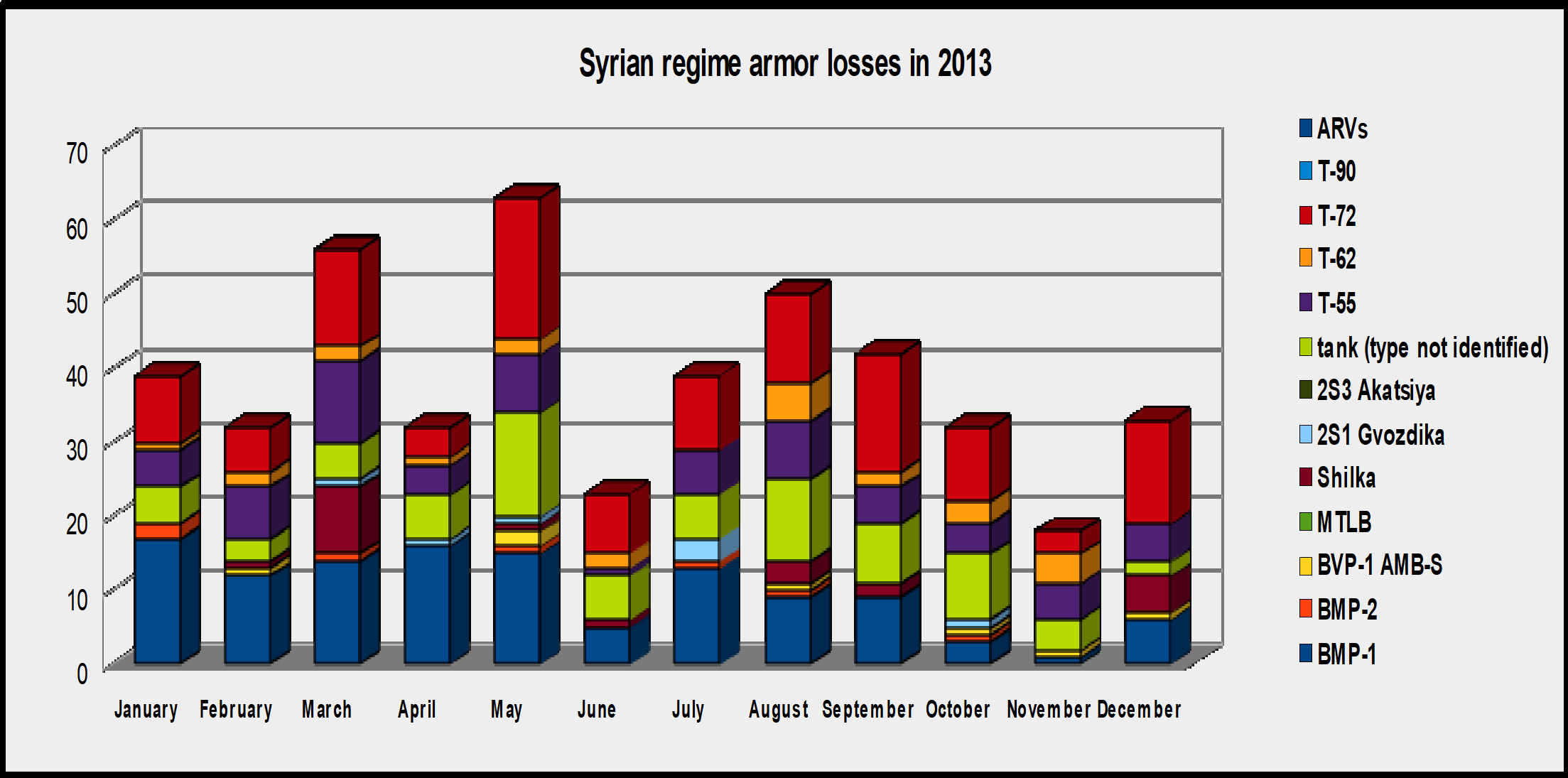

Armor Losses in 2013

In 2013, frontlines gradually solidified. Attempt to capture terrain required better organization which slightly favored the Syrian government with a unified command of its forces, albeit levels of corruption.

At the same time, opposition forces gained some experience and captured a substantial amount of ATGMs, which allowed them to overrun many poorly defended SAA bases. Some rebel groups began operating armored vehicles as well, not rarely captured in urban areas where the Syrian government had sent armored vehicles into rebel-held territory with minimal infantry support. This resulted in substantial losses.

In 2013, a total of 753 armored vehicle losses of the SAA were documented.

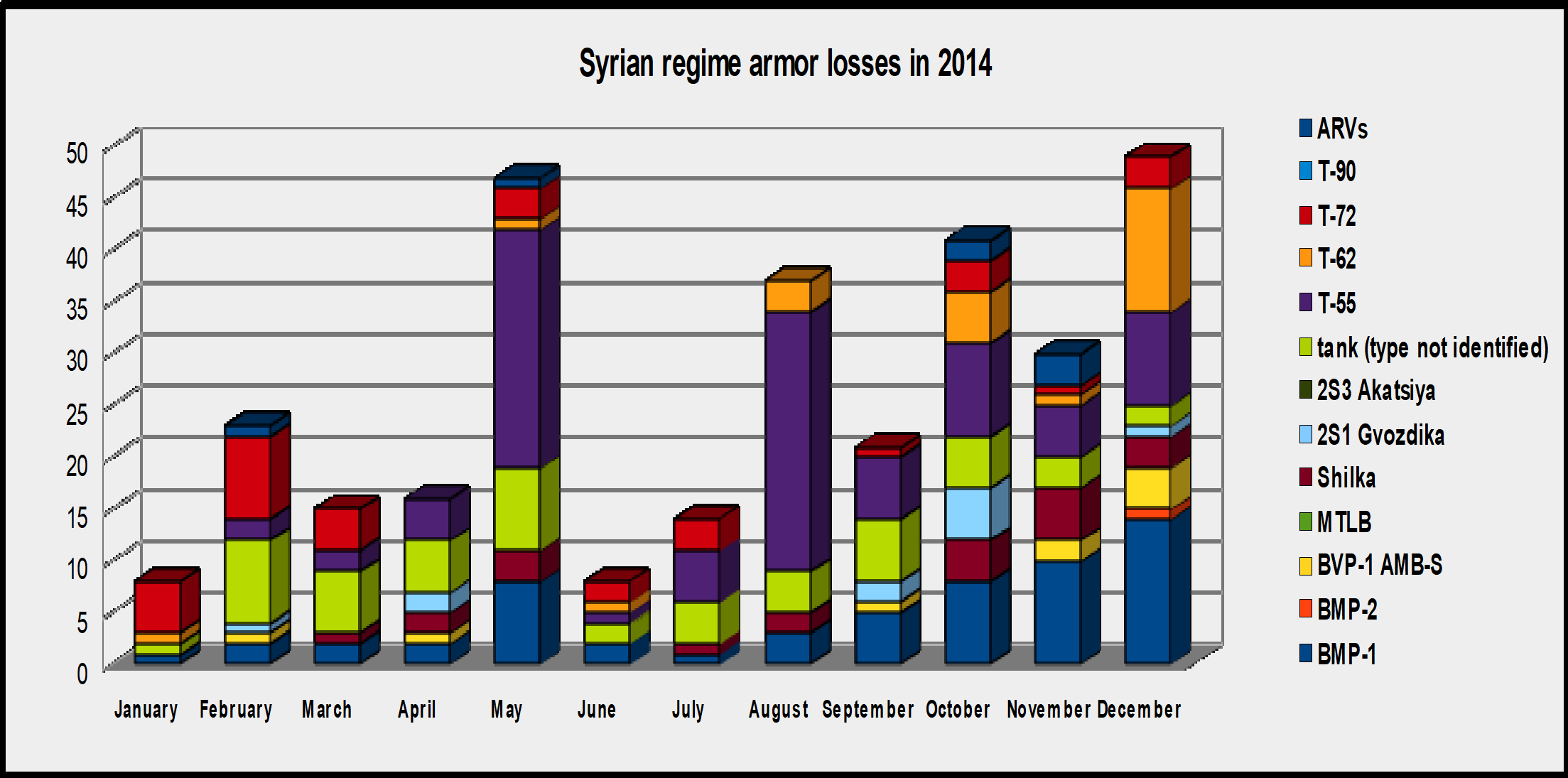

Armor Losses in 2014

2014 started with large-scale fighting between opposition forces and the Islamic State (IS) group. This initially diverted a lot of manpower and firepower from the anti-government forces, resulting in a decrease of armor losses to around a dozen per month.

However, after the frontlines between opposition forces and IS stabilized, the extremist’s group attention shifted towards countering Syrian government offensives and their isolated bases which often stored an incredible amount of weapons and ammo.

In July and August of 2014, IS overran several government bases in the Raqqa governorate, including the Brigade 93 base where it captured over a double dozen of T-55 tanks. A slightly smaller number of armored vehicles were later taken over by IS as it recaptured the Shaer gas field in October of that same year.

At least four T-55 tanks captured by the so-called Islamic State when the group took over the Syrian Arab Army’s 93 Brigade base in the Raqqa governorate. Photo published by @w_alraqqa on August 7, 2014.

In December, opposition forces launched a major assault in the Idlib governorate which resulted in the fall of the government’s Wadi Deif base and the loss of almost thirty armored vehicles.

Two captured T-62 tanks by opposition forces at the Wadi Deif base in the Idlib governorate on December 15, 2014.

One of the most effective weapons against regime armored vehicles have been ATGMs but until 2014 rebels had received only a small number of them from external sources and had to rely on capturing them from government positions. (These positions almost always contained way more weapons and ammunition than the defenders could reasonably use, even if they were trained to use that equipment.)

This relative scarcity of ATGMs began to change in the spring of 2014 when the United States allowed its allies (mostly Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Turkey, and Jordan) to start supplying TOW ATGMs to selected rebel groups under the Timber Sycamore program. Specifically, the TOW 2A was supplied, a model optimized to deal with tanks that are using reactive armor.

One of the conditions for getting new TOW missiles was to provide video evidence of their use; an anti-proliferation measure with the goal of preventing ATGMs from ending up with extremist armed groups. Hence, many TOW ATGMs strikes were uploaded to YouTube by the vetted groups, which made tracking SAA armor losses considerably easier. The number of supplied TOW ATGMs gradually increased as more rebel groups were approved to get them and more crews finished training.

Abu Hamza, at the time with Free Syrian Army’s 1st Coastal Division, operating a TOW in early 2015. Famed for his skills in operating the BGM-71 TOW.

A BVP-1 AMB-S captured by opposition forces in the Daraa governorate on February 1, 2014. Source.

A destroyed T-72 near Dear al-Adas in the Daraa governorate on October 1, 2014. Source.

In 2014, a total of 573 armored vehicle losses of the SAA were documented.

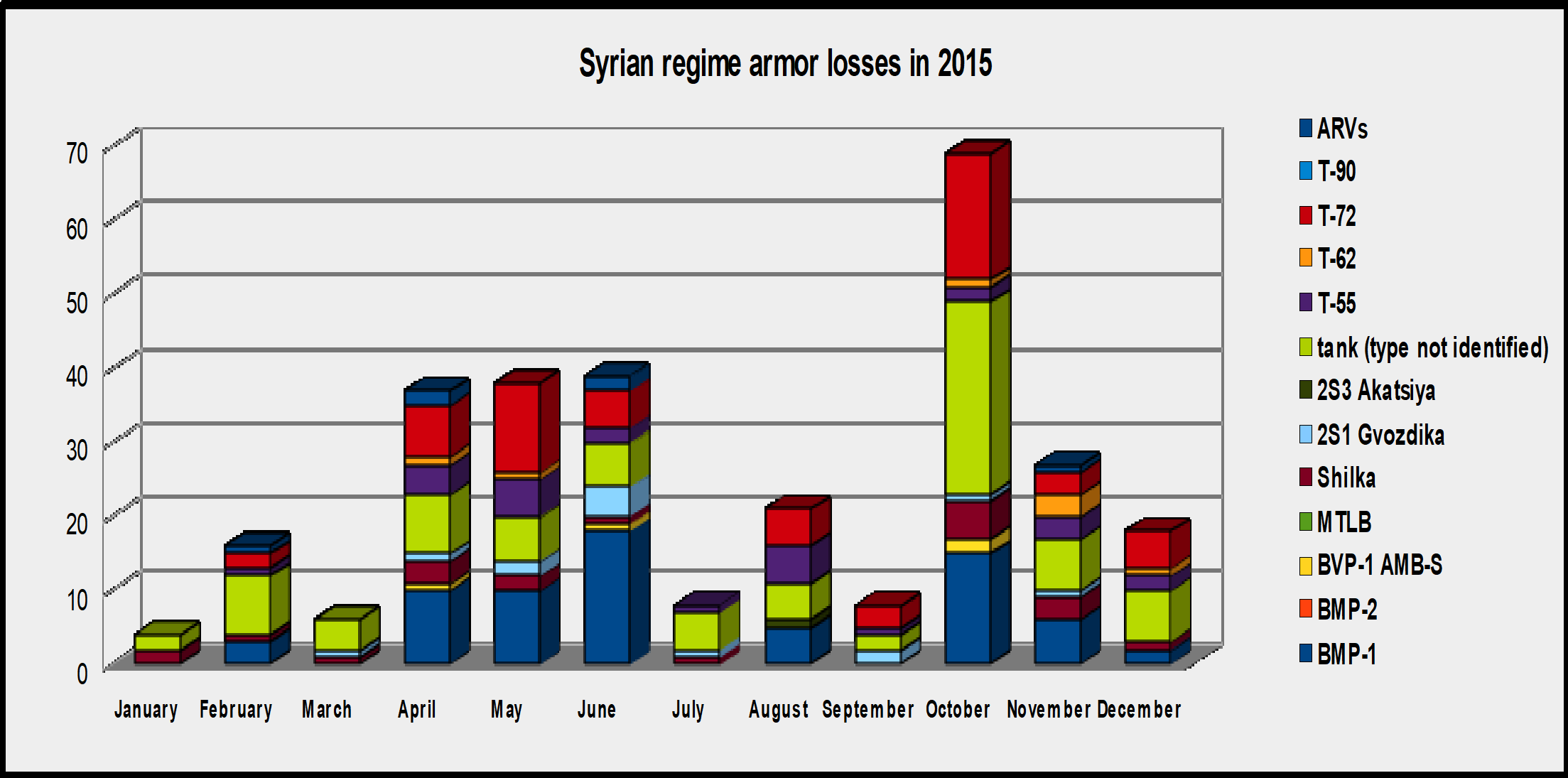

Armour Losses in 2015

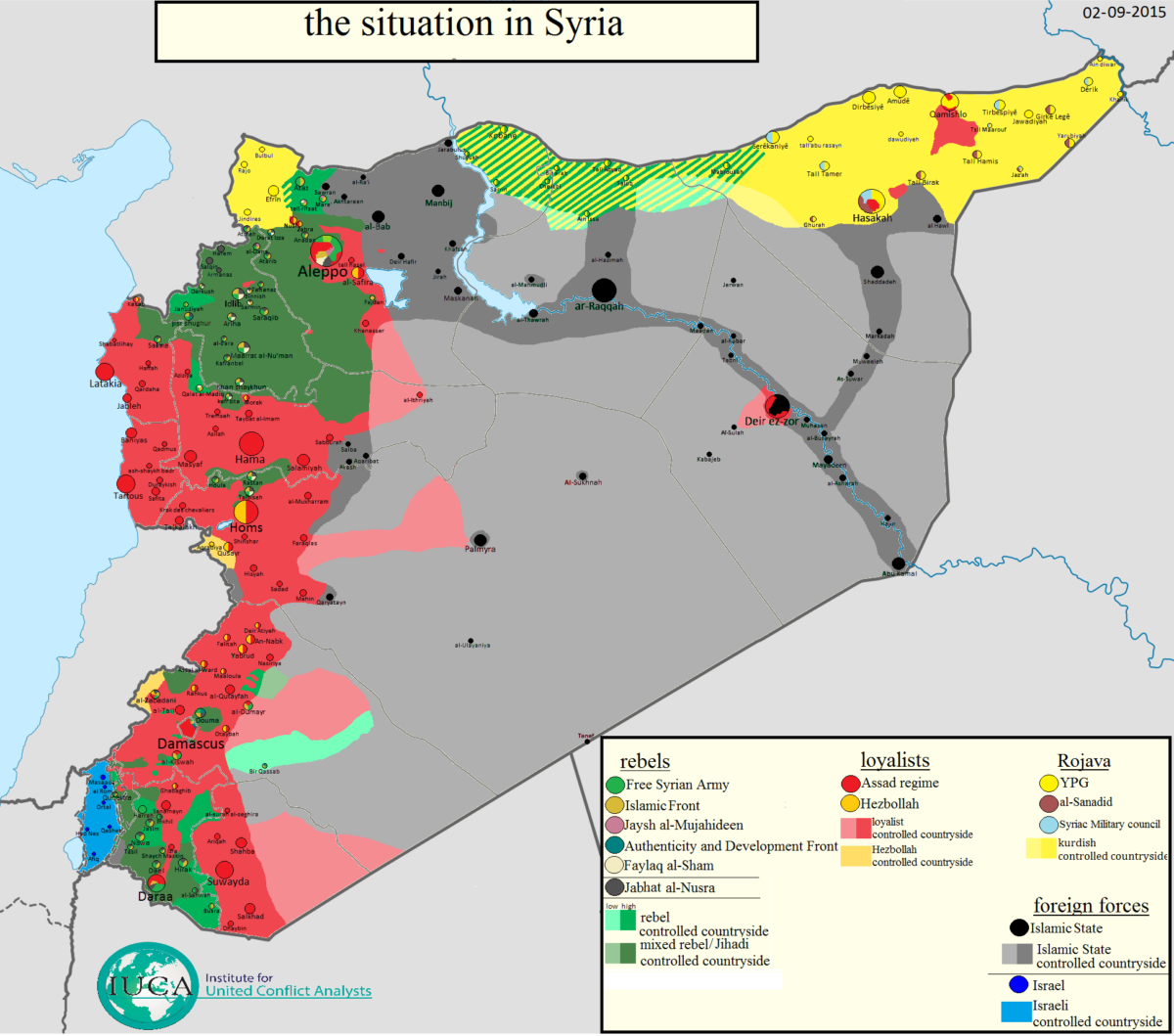

During the first nine months of 2015, Syrian government forces seriously struggled to regain the initiative after substantial losses in the second half of 2014.

Starting in late February, opposition forces combined their strength into a powerful alliance that came to be known as the Army of Conquest and launched a major, well-planned offensive in the Idlib governorate. The offensive was supported by a significant amount of external weapons and ammunition, especially TOW ATGMs. The latter was crucial in defeating the government’s tank-heavy counter-attacks.

In late April, rebels besieged around 250 government troops in the Jisr al-Shugour hospital, pressing Syrian President Bashar al-Assad to go on national television promising to lift the siege. Despite moving a large number of troops and heavy weapons – mostly from eastern Homs – into the area, all government attempts to lift the siege failed. This was partly due to the provenance of the TOWs in an ideal terrain for ATGMs: forested hills rising high above the plain which government forces had to use to reach the hospital. A breakout attempt resulted in the death of almost 85% of government forces.

View on the Ghab plain from a nearby hill. The villages of Ghaniyah, Kufayr, Frikka, and Al-Sirmaniyah are clearly visible. Source: Eyad Alhosain.

Note: Armour losses in Idlib were quite serious, but a lot of visual evidence is missing because it is around this time that YouTube starts deleting videos and even banning whole channels. Due to this armor loss count is significantly lower than it would otherwise be.

Intense fighting in southern Idlib has drawn a large number of remaining government “elite” mechanized units (most of the troops on both sides were practically unusable for offensives and “elite” units on all sides of Syrian Civil War would at best be seen as average troops in a competent army) which left area of eastern Homs governorate vulnerable and IS exploited this situation with what was initially just a raid that due to unexpected success when fighting very poorly trained regime troops was reinforced and turned into a real offensive that captured Sukna, Palmyra and oil/gas fields in that area.

This has become a low point for the Syrian government forces, which after these defeats controlled less than 20% of Syria and faced the prospect of rebels being able to gain firepower superiority at least in some areas. While the government was still in control of many major urban areas, IS was posing a serious risk to eastern Homs area, while rebels were making preparations for a large offensive which would try to repeat Idlib scenario and capture Hama city and a large part of Hama governorate – which would also cut off regime forces in Aleppo and put regimes stronghold Latakia in danger.

Shortly after this, Syria’s allies Russia and Iran decided to come to help. Russia moved dozens of planes and helicopters to the airbase in Latakia and Iran moved increasing numbers of military advisors, as well as Iraqi and Afghani proxy forces as well as Hezbollah reinforcements. into Syria to stabilize the situation. Emboldened by this increase in support, the SAA started a major offensive to retake northern Hama and advance into the Idlib governorate in October 2015. This resulted in a major battle against rebels who used around 140 ATGMs in that month alone, inflicting large losses on regime armored units and the regime even lost some territory in northern Hama. But rebels meanwhile took serious losses from Russian Air Force (RuAF) airstrikes which forced them to abandon large-scale offensive in Hama.

In 2015, a total of 409 armored vehicle losses of the SAA were documented. It is important to take into account that a disproportionate number of visual evidence from this year was lost.

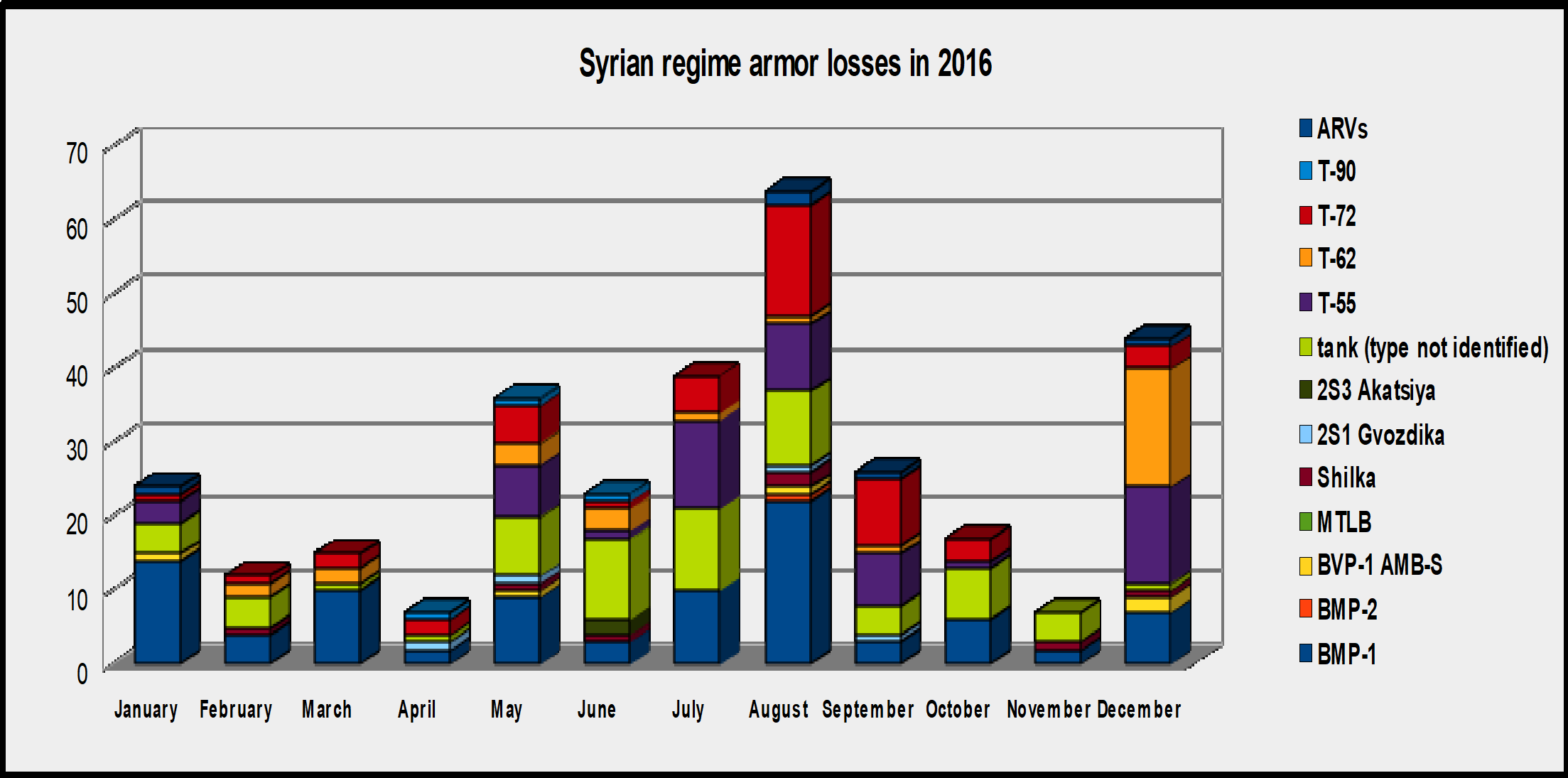

Armor Losses in 2016

In 2016, thanks to foreign reinforcements provided by Iran, air support from Russia, and small shipments of modern T-72 variants and T-90 tanks (And later larger shipments of T-62Ms and BMPs), the Syrian government started gaining the upper hand in the Syrian Civil War.

However, often when the SAA started an offensive in one place, it was in danger of losing ground elsewhere – even with air support of the Russian Air Force (RuAF). Losses were also inflicted upon the SAA by both rebel ATGM hits and ISIS mobile warfare tactics in the desert areas.

To take advantage of firepower, the Syrian government forces launched a series of offensives to link up with besieged Shia dominated towns in northern Aleppo, to recapture Palmyra, and, later, to besiege rebel-held part of Aleppo city. Just like in previous battles, the government forces depended on sheer firepower and a large number of armored vehicles leading mostly frontal assaults against prepared defenses. Mostly because of RuAF which was slowly but surely successful, but at a high cost to attacking units.

When government forces were distracted in one place, rebels repeatedly tried to regain the initiative by launching offensives in areas that were lacking troops. In spring, while fighting around Palmyra, rebels attacked northern Hama and while government reinforcements together with RuAF reversed rebel gains, they lost dozens of armored vehicles in a fairly short amount of time.

Something similar was repeated in late summer when government forces weakened other fronts in order to concentrate enough forces to cut off the rebel part of Aleppo and besiege it. Shortly after this was achieved regime was surprised by large rebel offensive in the southern part of Aleppo city which for several weeks lifted regimes siege of Aleppo and cut off regime part of Aleppo from supplies.

While reversing this rebel gain (which also cost regime a significant amount of troops and armored vehicles, rebels in northern Hama launched another attack and came very close to the city of Hama itself. While all these rebel offensives were ultimately defeated they showed how reliant is regime on RuAF air support and how weak it is even when faced two with enemies – one of which was bombed nonstop by RuAF and the other one by a US Air Force (USAF).

When by the end of the year defenses of rebel-held Aleppo started breaking down due to huge firepower provided by RuAF and Russian artillery combined with Syrian government ground forces, IS took the opportunity and swiftly defeated regime forces around Palmyra and captured the town. When regime forces run away they left behind around 2 dozen tanks which IS captured— most of which USAF soon destroyed.

In 2016, a total of 390 armored vehicle losses of the SAA were documented.

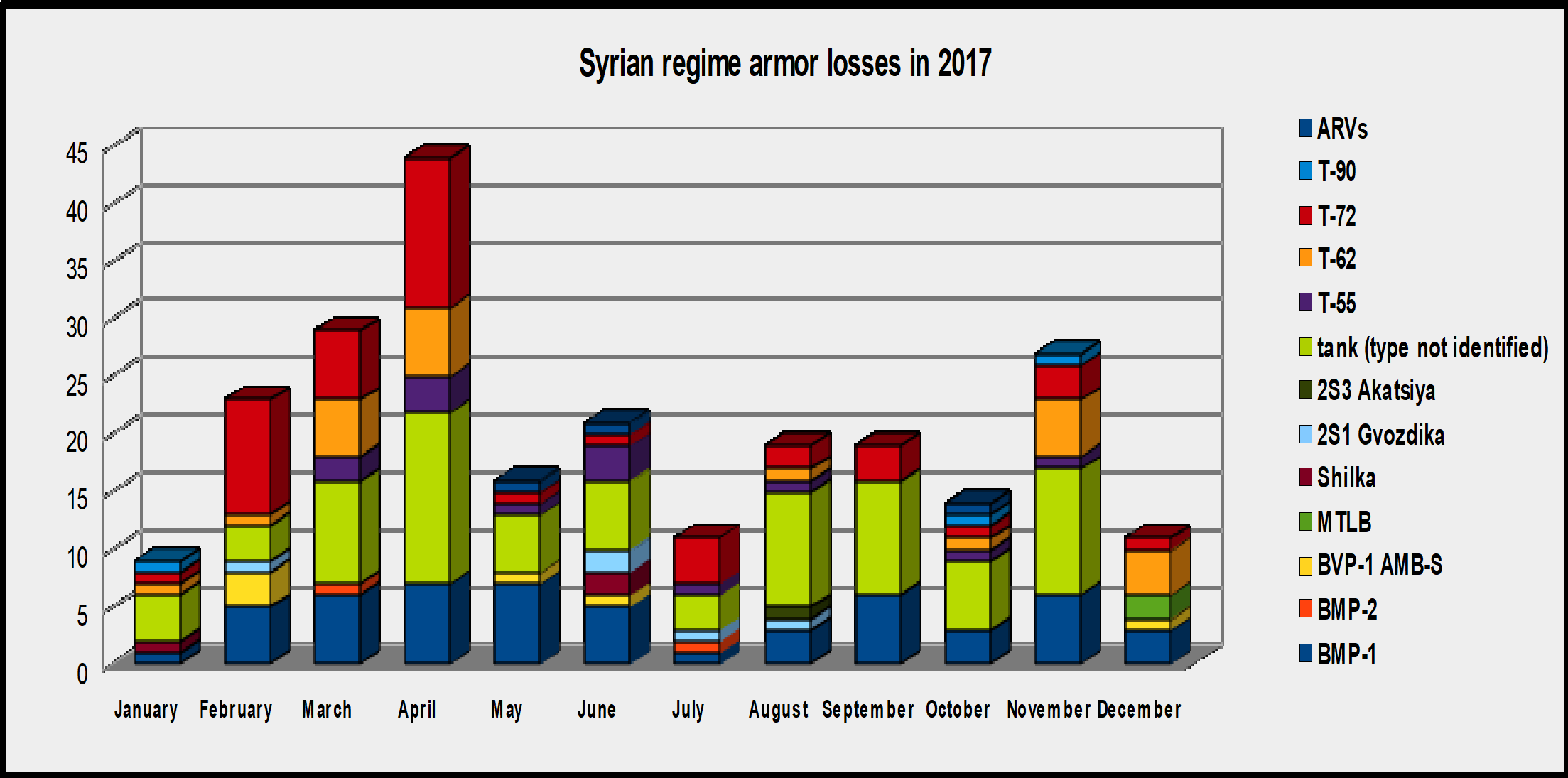

Armor Losses in 2017

By early 2017, the initiative was firmly in hands of the Syrian government as the IS militants were faced with a multi-front war and constantly under the threat of airstrikes of a dozen foreign countries, and opposition forces as well but then by RuAF. However, both opposition groups as well as IS were able to conduct only short offensives, which hurt government forces but could not stop their advance.

Also, in early 2017, the supply of TOW ATGMs significantly slowed down and a few months later aforementioned Timber Sycamore program was terminated. While both rebels and IS were still able to exact a significant price for government advances in their territory, they were only able to slow down this advance – rarely stopping or reversing it for longer than a few weeks.

Rebels were also significantly damaged by their infighting, which flared up any time they weren’t under pressure from the regime.

A T-90 destroyed by the so-called Islamic State in Mayadeen on November 16, 2017. The photo was published by the group’s media wing.

A T-90 destroyed by the so-called Islamic State in Mayadeen on November 16, 2017. The photo was published by the group’s media wing.

In 2017, a total of 294 armored vehicle losses of the SAA were documented.

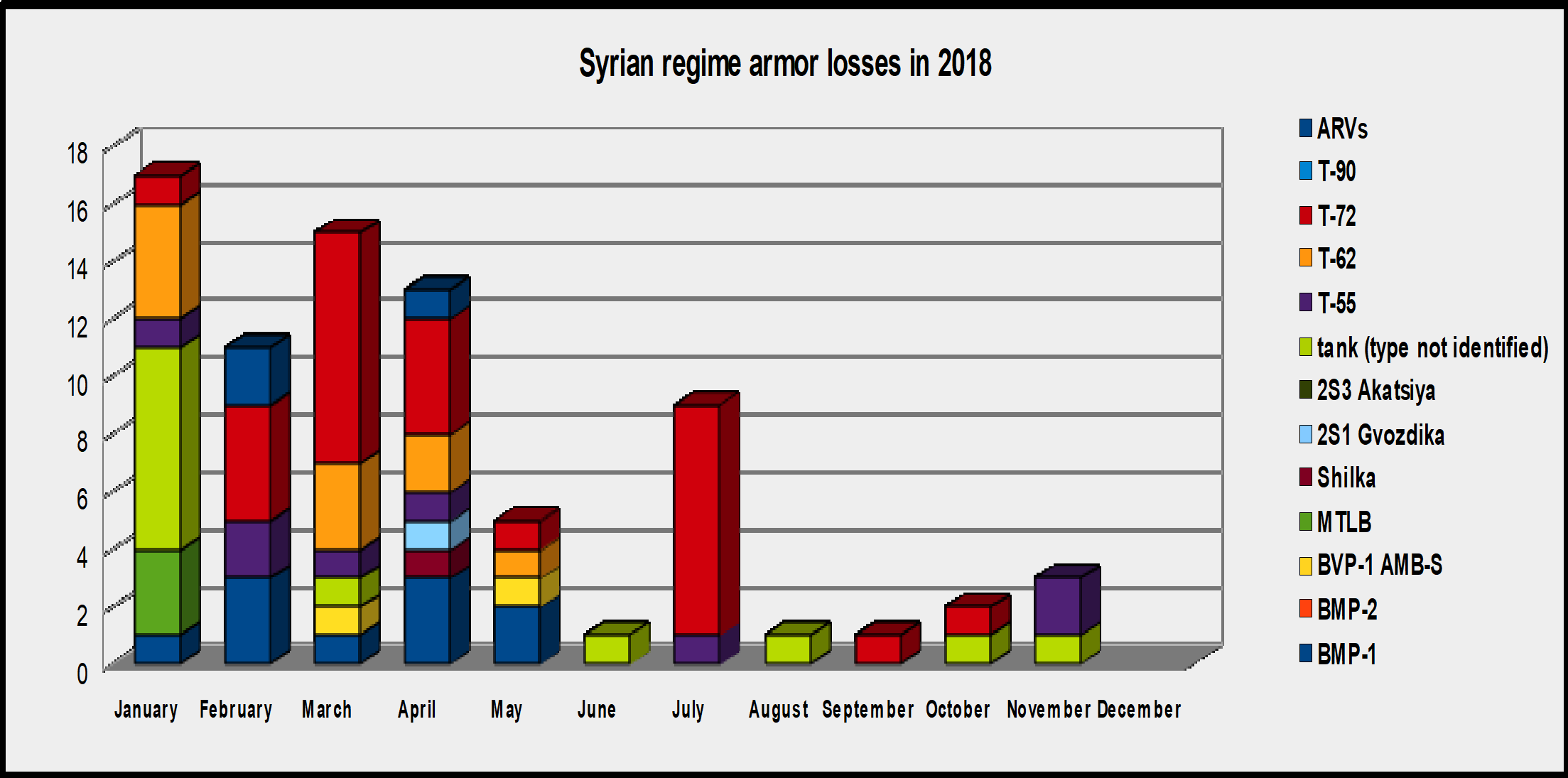

Armor Losses in 2018

The Syrian government started its 2018 campaign by eliminating the eastern Ghouta and eastern Qalamoon pockets east of Damascus and month of heavy fighting, at the end of which rebels in eastern Ghouta destroyed their remaining armored vehicles, while eastern Qalamoon rebels handed over around 30 tanks that were earlier captured back to the regime. Shortly after that, after a brief offensive, northern Homs pocket negotiated its own surrender deal. By summer, the same has been repeated in Daraa – leaving northern pocket centered around Idlib governate the only remaining territory held by rebels (northern Aleppo is held by Turkey and its proxies – those are rebel groups, but they act against the regime only when Turkey approves such action). Due to political agreement between Russia and Turkey (neither Assad’s regime nor rebels have any actual say in decisions that are taken) northern Syria frontline has been temporarily frozen.

Due to a degraded strength of opponents to the Syrian government, we have observed a declining % of regime armor losses being visually confirmed, since the regime and pro-regime media rarely publish evidence of their own losses.

In 2018, a total of 88 armored vehicle losses of the SAA were documented.

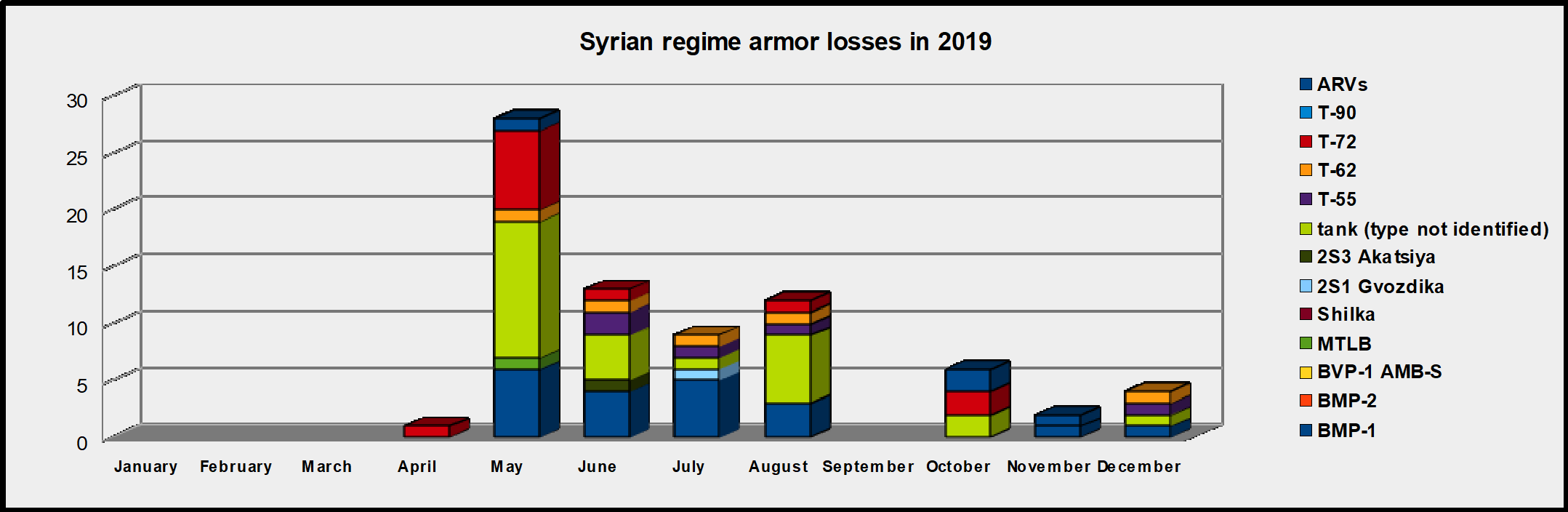

Armor Losses in 2019

There was a minimal frontline activity in early 2019 and fighting only restarted by late April after series of regime artillery and air strikes and rebel raids on regime positions. Most battles were concentrated in northern Hama and southern Aleppo around the town of Kafr Nabudah. Since Turkey opposed the regimes further advance, it has supplied some rebel groups with new shipments of TOW and Kornet ATGMs, which again proved helpful in slowing (and sometimes stopping) regimes advance – but Russian airstrikes made it difficult for rebels to hold (let alone gain) ground without taking excessive losses.

Losses in May and June made it impossible for rebels to do much about regimes later offensive in south-eastern Idlib – towards Abu al-Duhur airbase, which resulted in a significant loss of the remaining rebel territory.

The only frontline where rebels were able to defeat regime attempts to advance in 2019 was in north-eastern Latakia, around Kabanah hill, which dominates the area. There despite numerous attempts by regimes “elite” 4th Armored Division, rebels managed to hold the ground due to a mix of experienced fighters, difficult terrain and extensively prepared defensive positions.

In 2019, a total of 75 armored vehicle losses of the SAA were documented.

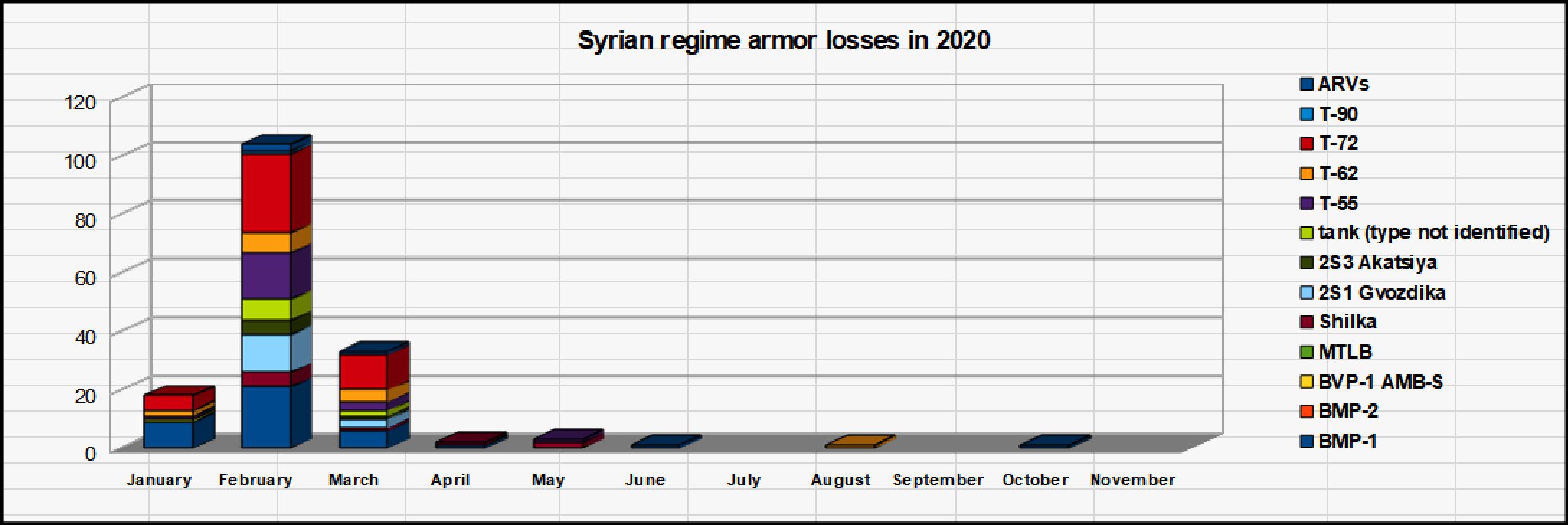

Armor Losses in 2020

2020 started with a continuation of regime advance deeper into southern and eastern Idlib, and by late January also in western Aleppo. After months of fighting regime forces, which had substantial support from their own artillery and Russian Air Force, rebels have, despite occasional battlefield successes like the capture of T-90 tank in southern Aleppo, started losing territory at an increasing rate due to material and manpower losses they have suffered over the past year.

As in 2019, Turkey has at first responded by shipments of TOW and Kornet ATGMs – this time in volume last seen in 2015/2016. This has significantly increased regime armor losses, but the weakness of rebel frontlines has allowed the regime to continue its advance. Regime forces have also during this time hit Turkish troops several times, inflicting casualties. At that point, the government of Turkey apparently came to a conclusion that direct use of its military will be needed to stop and potentially reverse regimes advance, which was absolutely necessary to at least temporarily avert a huge humanitarian disaster – regimes offensive has by that point displaced more than a third of 2.5 million people living in rebel-held areas (large % of whom would likely be arrested, tortured and murdered, if regime captured them).

As a result between February 10th and 15th, Turkey started using its armed drones (Bayraktar TB2 and TAI Anka) and it’s artillery units that were deployed in the rebel-held territory to strike regime artillery, armored vehicles, and concentrations of infantry. What was interesting about this action is that this use of force has mostly stayed hidden from the public for about 2 weeks (TAI Anka-S was shot down by regime forces on February 25th but it didn’t gain too much attention). After a Su-24 (which are operated by both Assad’s regime and Russian Air Force) bombed Turkish military position on February 27th, inflicting significant casualties, Turkey revealed to public recent footage of its combat drones attacking regime targets and increased intensity of these strikes in revenge for attacks on its troops.

These drone strikes have quickly degraded regimes units on the frontline, as well as their artillery support, which in turn allowed rebels to advance – regaining some of the previously lost territory and capturing a large number of regime armored vehicles that their crews abandoned – at least partially due to their fear of Turkish drone strikes. The final result of these events is a near-unprecedented level of losses of armored vehicles for Assad’s regime – 104 armor losses have been visually confirmed and many more were claimed by Turkey – but only some of the drone strike footage has been released. The only comparable period of such heavy losses during the Syrian Civil War is July 2012, when the regime lost 109 armored vehicles. At this point fighting again stopped due to a new agreement between Turkey and Russia.

In 2020, a total of 164 armored vehicle losses of the SAA were documented.

Summary and Analysis

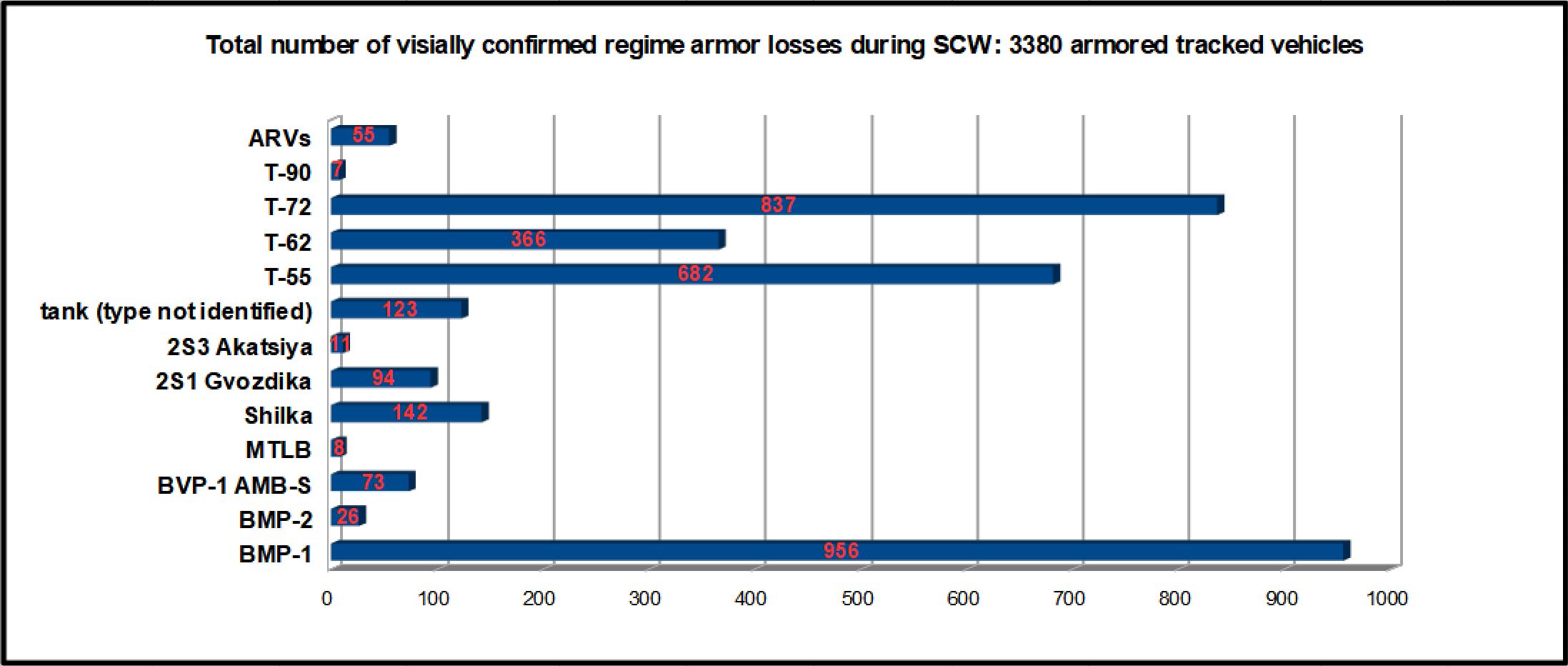

A total of at least 3380 armored vehicles of the Syrian government have been destroyed since the start of the Syrian Civil War (numbers updated in late March 2020), based on extensive analysis of visual footage shows.

Lost vehicles by type:

When one considers that many more potential losses lack visual evidence, the actual number of losses for the SAA may be much higher. This is also because the number of armored tracked vehicles at the beginning of the conflict was likely to be an overestimate of the actual number. Besides, Russia shipped a number of its tanks (mostly T-62Ms) to Syria. The 6th largest tank fleet in the world has arguably been destroyed.

A number of destroyed armored tracked vehicles (1x T-72, 4x BMP-1, 1x BVP-1 AMB-S) near Adra, Damascus, on February 27, 2013.

Arguably, several reasons can be mentioned why the Syrian armed forces lost so many armored vehicles during the course of the ongoing Syrian Civil War. A few can be especially highlighted, the author believes, such as the civil war in general, large quantities of weapons and ammo being stored in indefensible locations combined with lack of preparations to destroy weapons and ammo in case of retreat, incompetence of army units (fueled by the fact that officer promotions are being driven by bribes and perceived loyalty, instead of competence), the inability or unwillingness to learn from previous costly mistakes, the lack of proper combined arms training, obsolete equipment, and proliferation of powerful anti-tank weapons. Turkish drone strikes in early 2020 have also shown that what remains of the Syrian military is only an empty shell and it would serve only as a speedbump against any modern army.

The author would like to thank all my friends for their invaluable help, with special thanks to @MENA_Conflict, @oryxspioenkop, @QalaatAlMudiq, @adambrayne7, @SCW_Nuggie, @DLAMNscw, @Mr_Ghostly, and the whole Bellingcat Investigation Team.

Lastly, the author would like to thank the ‘SFM’ group (you know who you are) for sharing working links to footage that was likely to be quickly removed from public websites.