Watching the World Burn: Islamic State Attacks Against Libya's Oil Industry

Contrary to other armed groups in Libya, the strategy behind the Islamic State’s attacks on oil facilities is not purely military. It is also part of a wider strategy calling for the disruption of the oil industry, not only to affect opposing regimes but also western society and the global economy. Damage to oil facilities can have severe negative consequences for the environment and public health. Interestingly, Al Qaida’s strategist Abdullah bin Nasser al-Rashid wrote guidelines for attacks on the oil industry, which also took into account environmental and public health considerations and the preservation of natural resources. But with this week’s attacks on oil installations in Libya, IS seems to be diverging from this position and is taking a more destructive approach.

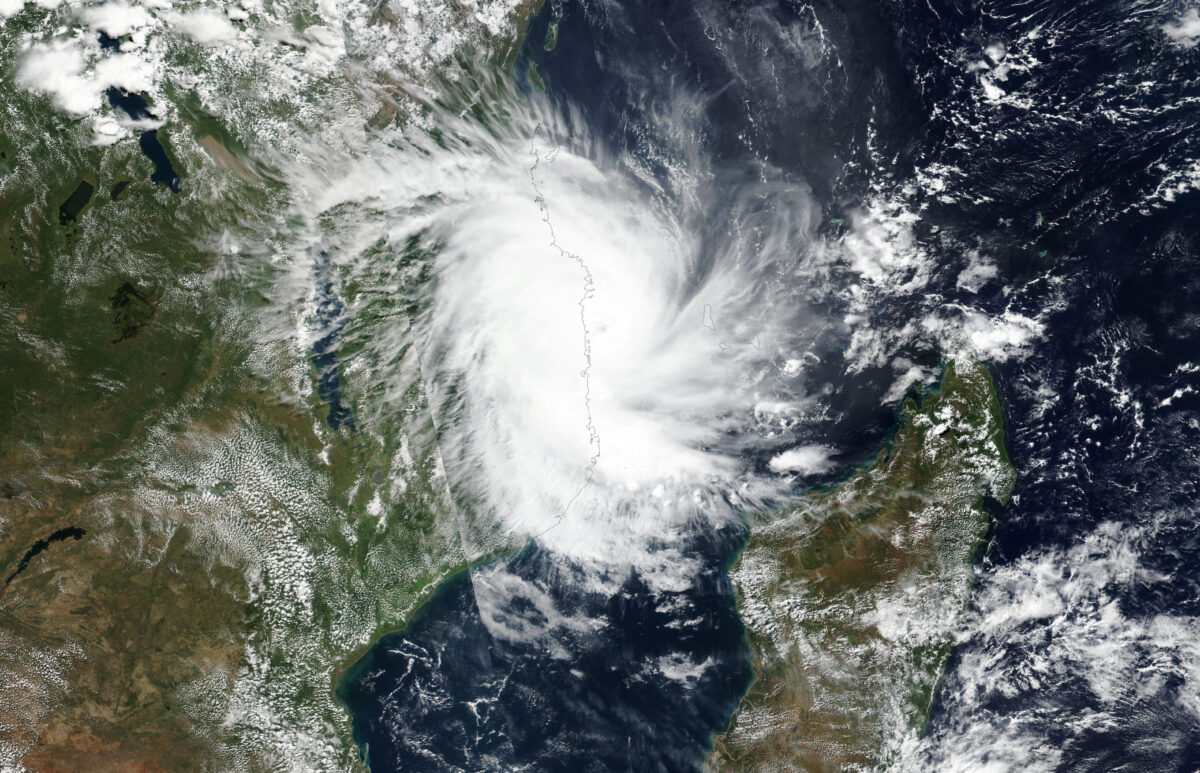

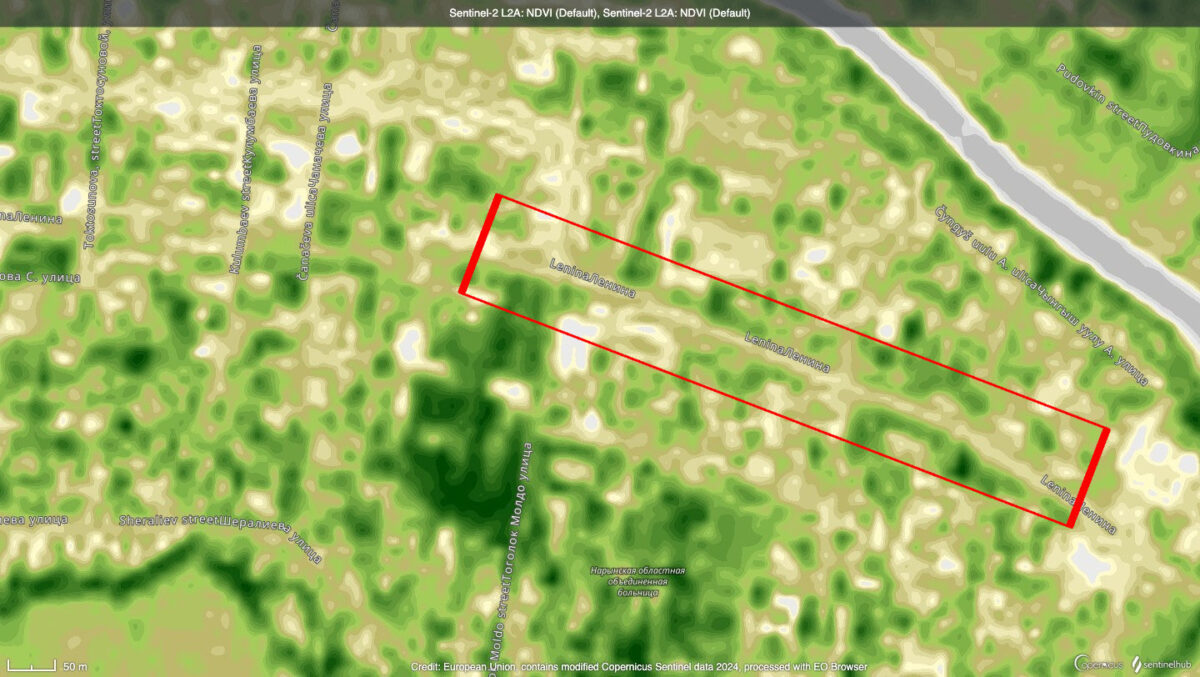

Burning oil storage tanks south of Ras Lanuf, January 6, 2016. Image by ESA/Sentinel 2.

IS groups in Libya are currently staging attacks on the oil industry in As Sidr and Ras Lanuf. The attacks on export storage facilities have seen five oil tanks set alight, each containing 400,000 barrels of oil; with one facility taken over. Libya, as a petrol-state heavily dependent on oil revenues, has witnessed frequent attacks by a variety of rebel groups on its oil facilities. As noted by the International Crisis Group, the collapse of Gaddafi’s regime precipitated a range of oil disputes as corrupt individuals and militias fought over the spoils. For example, in December 2014, during Operation Sunrise, which was led by the Libya Dawn coalition, damage to oil installations resulted in the burning of 1.8 million barrels of crude oil.

Burning oil storage tank, Sidr, December 2014

And in February 2015, an IS attack on the Mabruk oil field resulted in 12 people being killed, and a halted production at the 40,000 barrel a day facility. With the rise of IS, battles between federalist, Islamist and other factions over access to oil resources have dramatically increased. As a result, Libya’s total oil production has dropped to less than 600,000 barrels a day, from the 1.65 million barrels per day before the civil war erupted.

The recent waves of attacks by IS has brought a new element to the conflict, namely the intentional destruction of oil facilities in order to create an economic collapse. As outlined [PDF] by Libyan IS spokesperson Al-Qathani, in IS magazine Dabiq, IS’s aim is to cripple Libya’s oil industry: “[Libya] also contains a well of resources that cannot dry. All Muslims have a right to these resources. […]It is important to note also that the Libyan resources are a concern for the kāfir West due to their reliance upon Libya for a number of years especially with regards to oil and gas. The control of the Islamic State over this region will lead to economic breakdowns especially for Italy and the rest of the European states.”

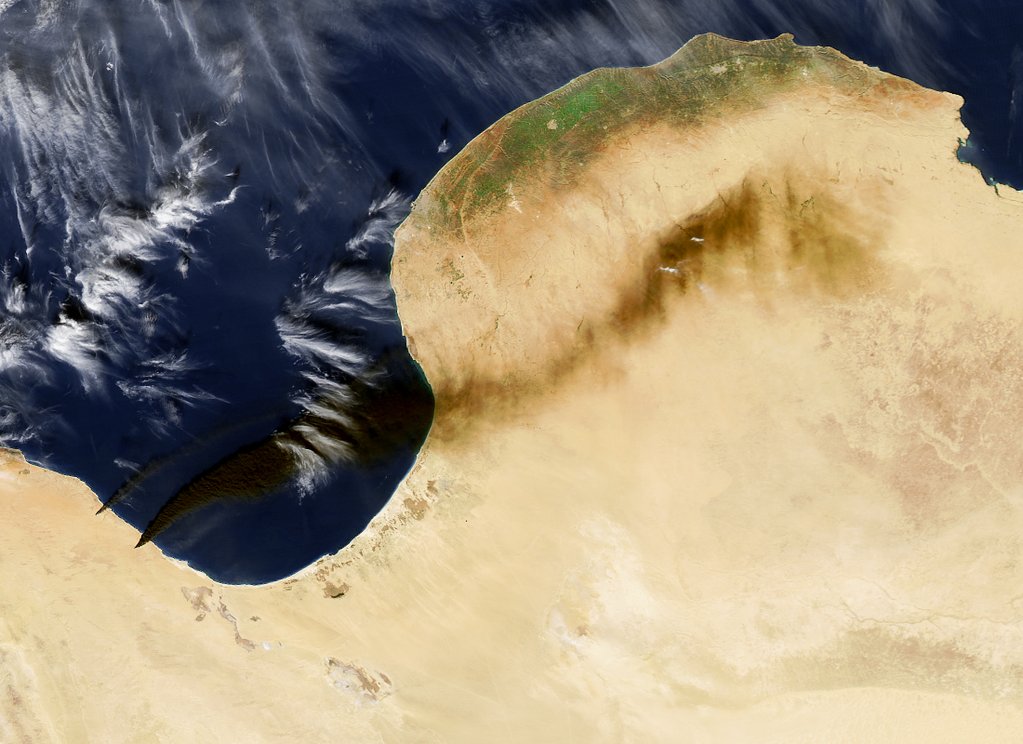

Initial geolocation of these sites located attacks on oil storage sites south west of Sidr and south of Ras Lanuf, and NASA satellite images showed considerable damage and huge smoke plumes at these sites. While tackling the blaze, the commander of Sirte’s fire brigade made an appeal for help to the UN, as they are facing an “economic and environmental disaster”.

Oil plumes across the Mediterranean Sea, January 6, 2016. Image by NASA/Modis

Jihad and economic destruction

To understand the reasoning behind this strategy, it’s important to look further into jihadist thinking on natural resources and what constitutes a legitimate attack. Osama Bin Laden pointed out the dependency of the West on Arab oil resources and attacked the Saudi Arabian government for supporting the West in stealing these natural resources from Muslims. He justified attacks on the oil industry as a means of low-intensity warfare to prevent the theft of natural resources through the Saudi state by Western governments, which resulted in attacks against foreign oil companies in Saudi Arabia and the failed attack on the Abqaiq oil facility. While in 2002, Yemen experienced a successful attack against the Limburg, a French oil tanker.

These considerations where later rooted in a theological rationale and became part of Al-Qaida’s strategy when targeting the oil industry. It was outlined in their directive in 2004, written by Al Qaida’s strategist Abdullah bin Nasser al-Rashid, called The Laws of Targeting Petroleum-Related Interests. Al Qaida considered these tactics as a means to inflict economic damage to the Saudi government and US interests. The strategy divided legitimate petroleum industry targets into four categories:

“a. Oil wells: The targeting of oil wells is not permitted as long as an equally powerful alternative exists. This is because the negative consequences of such an operation outweigh the benefit.

b. Oil pipelines: These are among the easiest targets to attack. The benefits of attacking pipelines outweigh the costs.

c. Oil facilities: These are not to be targeted if they are privately owned by a Muslim.

d. Individual leaders from the petroleum industry: these are among the easiest targets to attack, and the benefits of such operations far outweigh the disadvantages—as long as [spilling] the blood of the person who is being targeted is permissible. As for industry leaders whose blood has not been permitted, they should not be targeted except in situations where there is no other choice but to attack a facility they are currently located in…”

However, the strategy did note that “operations against oil wells […] are also detrimental to the environment and to public health. Moreover, attacking the oil wells also means forfeiting the opportunity to use them again once the Muslim nation reassumes ownership over them. Interestingly enough, after some deliberations on the costs and benefits of using such a tactic, the directive advised against attacking oil wells, “…because of the negative impact on public health and the environment” and stating that it prevents future use, whereas attacks on “oil pipelines and “facilities” seemingly have less of an environmental and public health impact and are therefore viewed as legitimate.

These reservations are interesting, as they reflect environmental considerations in military operations, a discourse that is under-addressed at present. For example, during the intense bombing campaign by Russia and the US on IS controlled oil sites in Syria. Environmental damage from attacks on oil facilities can result in acute and long-term public and environmental threats. Oil fires release harmful substances into the air – including sulphur dioxide, nitrogen dioxide, carbon monoxide, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and lead. These can be transported over a large area before deposition in soils, potentially causing severe short-term health effects for people and wildlife, especially people with pre-existing respiratory problems. Damage to oil storage sites and processing facilities can lead to the release of a range of dangerous substances. Groundwater contamination can threaten agricultural land and the people who rely on ground and surface water for irrigation, drinking, and domestic purposes. Long-term exposure to hydrocarbon pollutants may lead to respiratory disorders, liver problems, kidney disorders and cancer

The importance of inflicting economic damage by attacking the oil industry was also reflected in the writing of Babu Mus’ab Al-Suri, another Jihadi ideologist and strategist. In discussing the strategy of the new jihadist global autonomous cell structure and their primary targets, he wrote: “So, the most important enemy targets in detail: First, the oil and sources of energy from the source until the drain: These are among the most important targets of the Resistance: “Oil fields, oil pipelines, export harbours, sea navigation routes and oil tankers, important harbours in their countries, storage depositories in their countries…”[1]

Targeting natural resources.

Due to its inherent vulnerability, the oil industry has traditionally been a key target for terrorist groups, especially in the Middle East, where many governments are dependent on oil revenues. These industries are usually concentrated in certain parts of the country, often isolated, and therefore relatively easy targets and, if successful, attacks can have major national and international implications. Considerations similar to those rooted in Al Qaida’s strategy are likely key to IS’s strategy in Libya as well: to cause economic damage in order to destabilise the energy market and prevent both national parties in Libya as well as Western states from profiting from the oil revenues. Economic disruption may also damage efforts to bring Libya’s warring factions together.

Whereas other factions fight over access to natural resources in order to control and make a profit out of them, a strategy IS also uses in Syria, the IS groups in Libya appear to have few qualms about inflicting heavy damage to the oil industry. Yet, some commentators also consider it part of a tactic to inflict damage to oil installations, making them less valuable for their owners, and therefore too risky to protect. As a result, they are easier to take over. The recent clashes with IS attempting to take over access to Ajdabiya could cut off all supplies to the ports and gas fields, and has been said to be a “game-over” for Libya’s economy.

In light of IS’s destructive rationale behind the recent attacks, the Libyan forces in control of the remaining oil facilities, as well as the states supporting these groups should step up their efforts to protect facilities. Although it might seem that IS shares similar theological considerations with Al Qaida’s Al Rashid guidance, and therefore would ideally aim for preservation of these sites, the recent attacks indicate an appetite for their destruction, rather than preservation. In the Libyan context, it may be that IS views economic and political disruption and damages to natural resources as a more valuable commodity than oil.

[1] Cook, David (2008) Oil & Terror. In: The Global Energy Market: Comprehensive Strategies to Meet Geopolicital and Financial Risks. The G8, Energy Security, and Glboal Climate Issues. Accessed at: https://bakerinstitute.org/media/files/Research/b5edc3ae/IEEJoilterrorism-Cook.pdf

Thanks to Doug Weir from the Toxic Remnants of War Project for additional comments and edits.