Russia's "Anti-Selfie Soldier Law": Greatest Hits and Implications

After months sitting in the Russian State Duma, a law will finally pass forbidding Russian servicemen from carrying or using internet-connected devices to share information about their military units and service. The law introduces additional restrictions on Russian servicemen from sharing information about the military, including speaking with journalists about their military service or “carrying any device capable of recording or storing information” that could be shared online. In short: old Nokia phones with Snake pre-installed on them are about to get a lot more popular among Russian soldiers.

While this law has generated headlines across Russia and the rest of the world, efforts have long been underway to reduce instances of soldiers publicly sharing information and using smartphones on base, though with mixed success.

Trophy wall of soldiers’ contraband smartphones nailed to a wall in a Russian military base (Source: Pikabu via DFRLab)

Russia is far from the only country that has instituted such a law — Turkey, for example, allows their soldiers to only have “dumb phones” on-base after revising a law in 2015, leading to a surge of demand for non-internet connected cell phones.

Greatest Hits

There is not a single incident over the past five years that has led to Russia passing this law, but a handful of investigations assisted by oversharing from Russian soldiers may have played into the decision-making process.

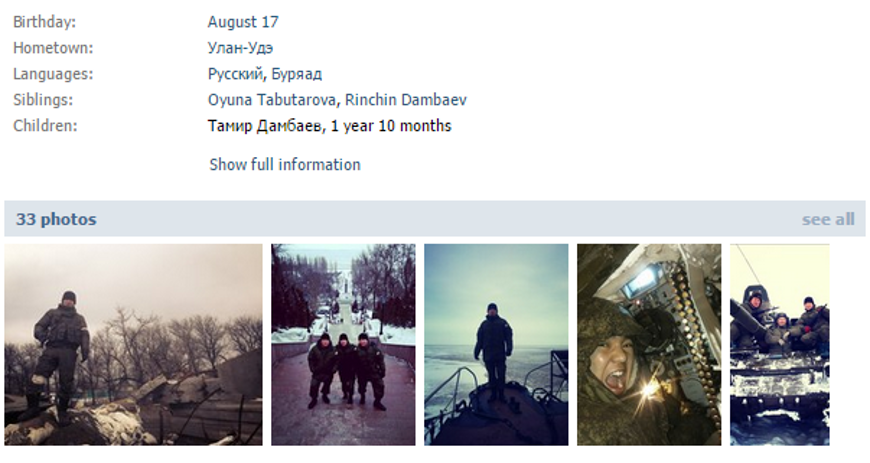

Bato Dambaev, the Puppy-Loving Selfie Soldier

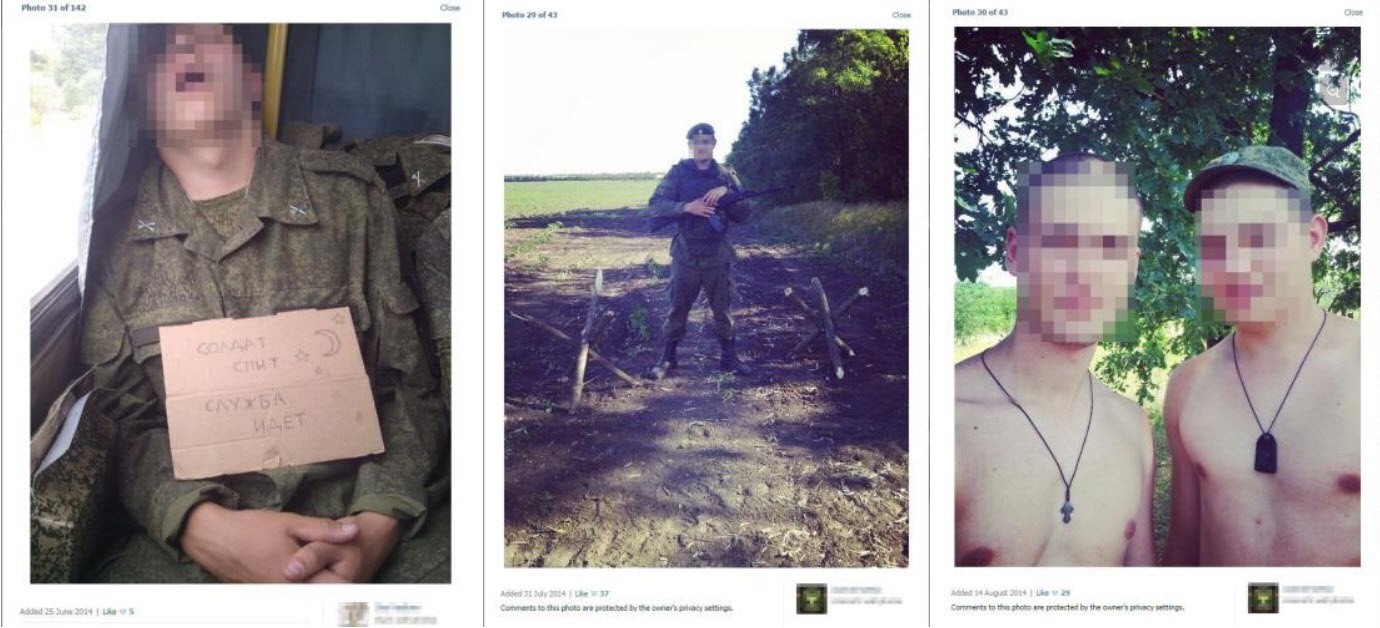

In 2015, Simon Ostrovsky filmed a popular documentary titled “Selfie Soldiers: Russia Checks in to Ukraine” for VICE News, going off of research started by Bellingcat following an investigation by Novaya Gazeta’s Elena Kostyuchenko.

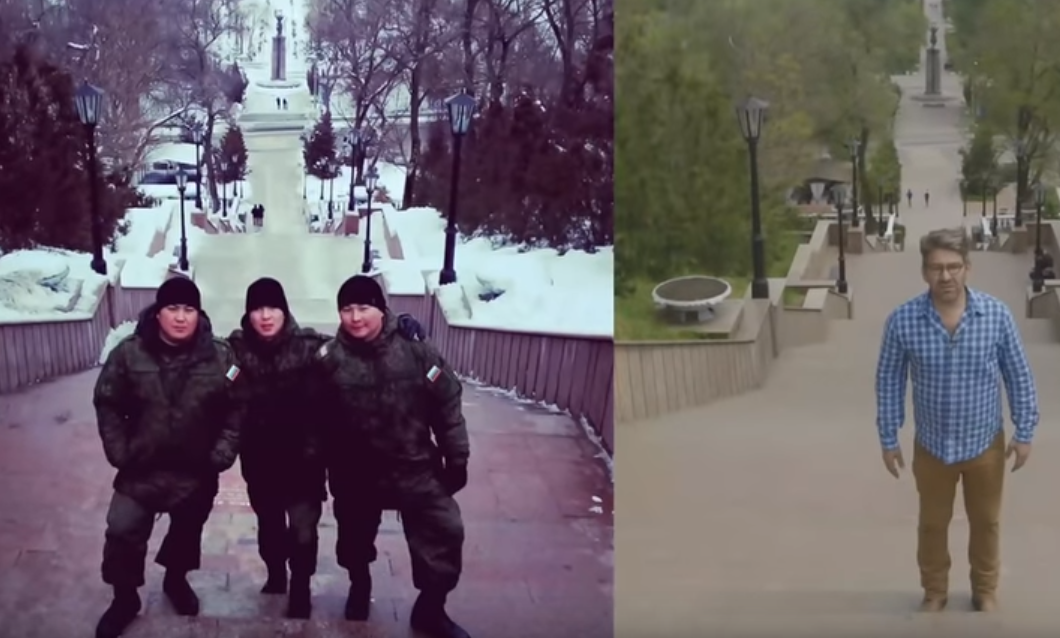

The documentary, which can be watched in full above, details how a young Russian serviceman named Bato Dambaev, of the 37th Motorized Infantry Brigade (Kyakhta), posted a photograph of himself at a checkpoint in Vuhlehirsk, Ukraine during the Battle of Debaltseve. Bato shared numerous photographs of himself at a base near the Russia-Ukraine border in early 2015.

Simon retraced Bato’s steps across Russia and into Ukraine, where he recreated a number of Bato’s photos, including the one in Vuhlehirsk.

Geolocating a photograph can be convincing, but recreating a photograph in the same pose as a Russian soldier leaves little doubt exactly where they were.

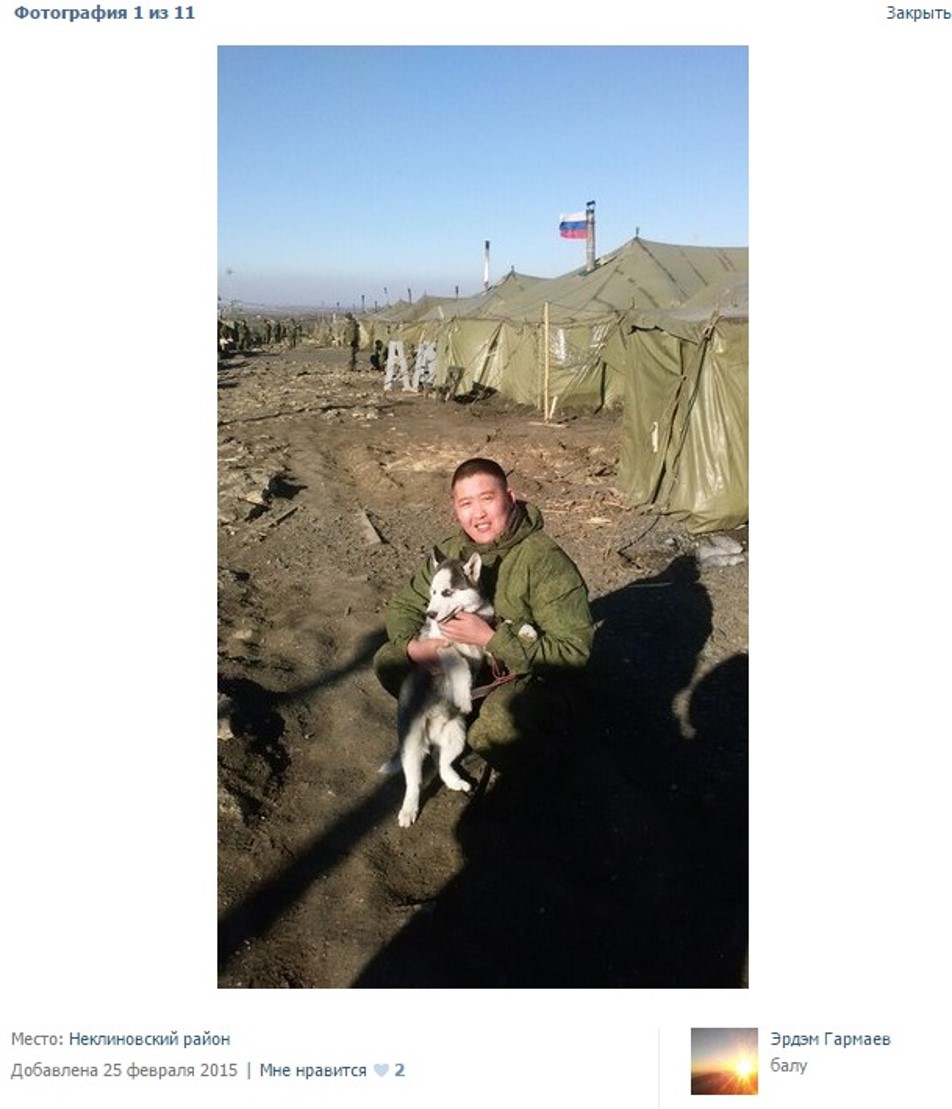

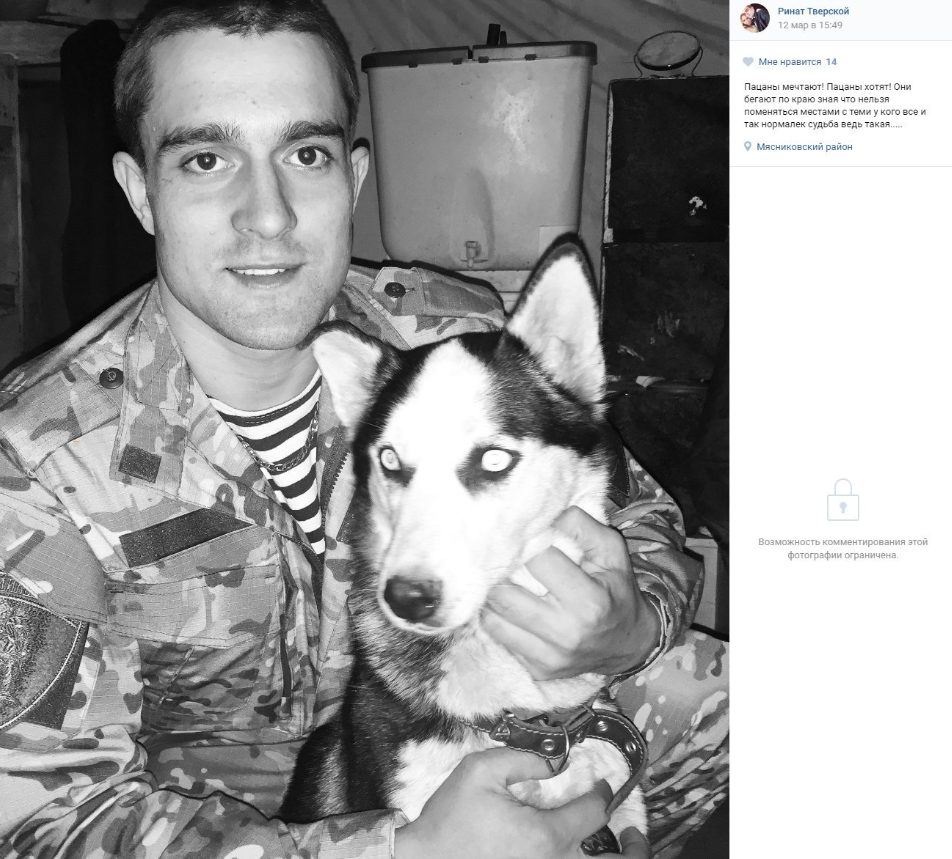

Not all of the photographs Bato uploaded onto his Vkontakte (VK) page have geopolitical implications — Bato and a number of his fellow soldiers posted photographs of themselves with their camp’s most popular residents: two Siberian husky puppies.

Years after Bato and his colleagues posed with these puppies before fighting in the Battle of Debaltseve, new Russian soldiers cycling through the same base also post pictures of themselves with these same huskies, though they are no longer puppies.

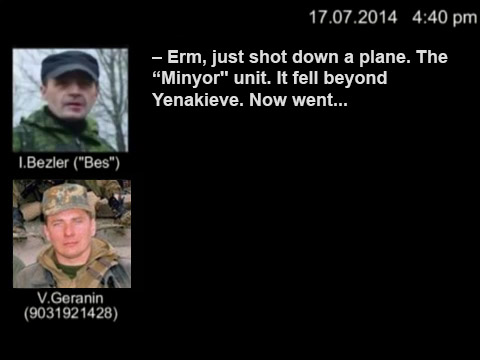

MH17 and the 53rd Brigade

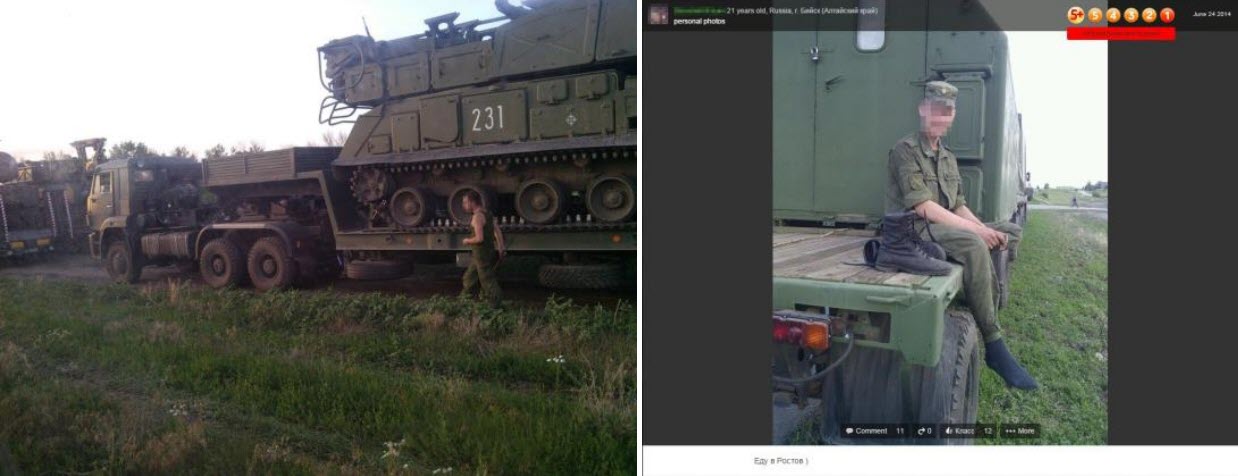

Tracing the origin of the Buk missile launcher that downed Malaysian Airlines Flight 17 (MH17) would have been possible without social media, but it was made a whole lot easier thanks to the servicemen of Russia’s 53rd Anti-Aircraft Missile Brigade, based in Kursk.

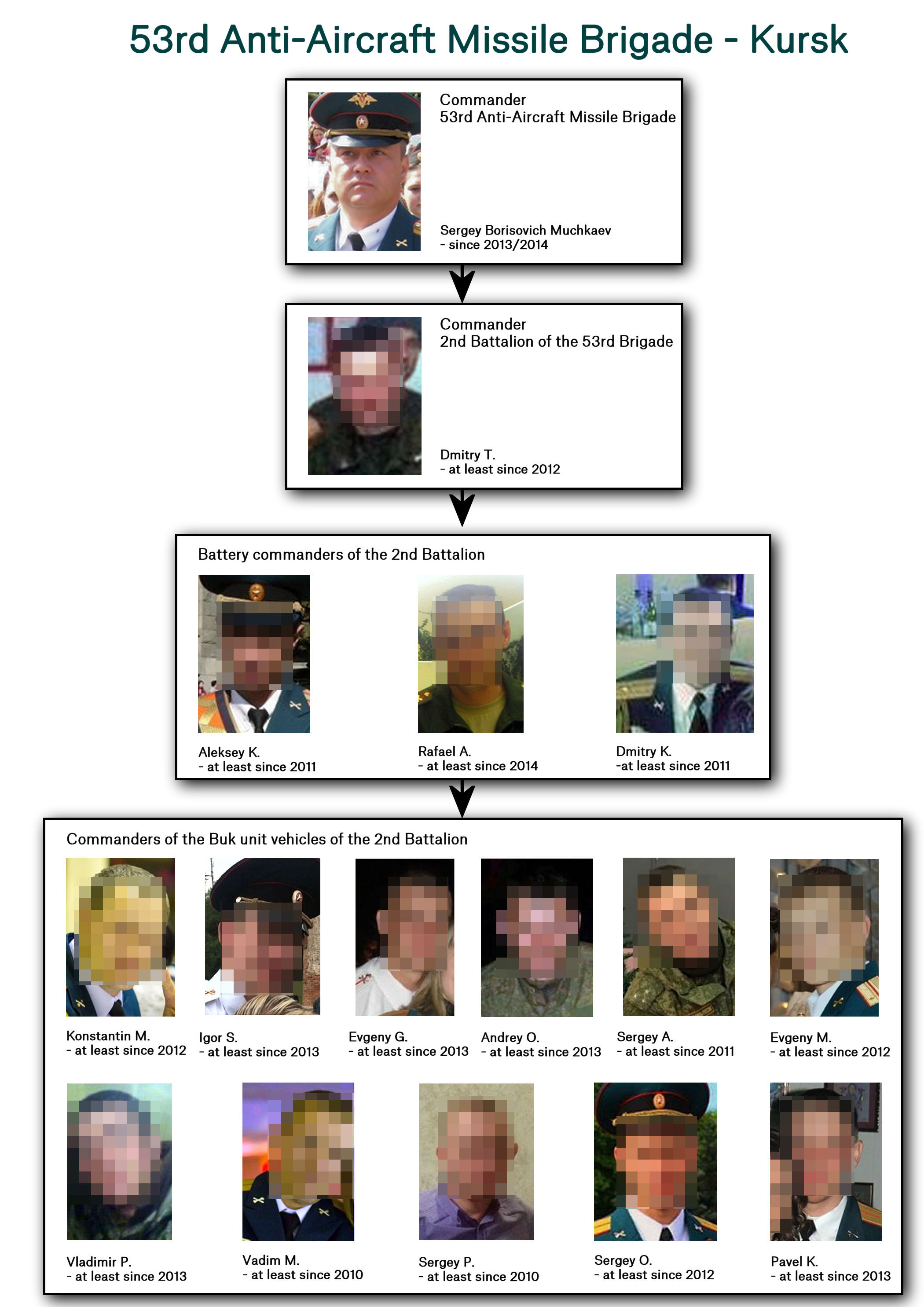

As we detailed in a 115-page (yes, 115) report published in 2016, the digital traces left by the members of the 53rd Brigade were extremely helpful in reconstructing the ranks of the military unit, along with providing vital information on the missile launcher that came from this brigade to eastern Ukraine in July 2014.

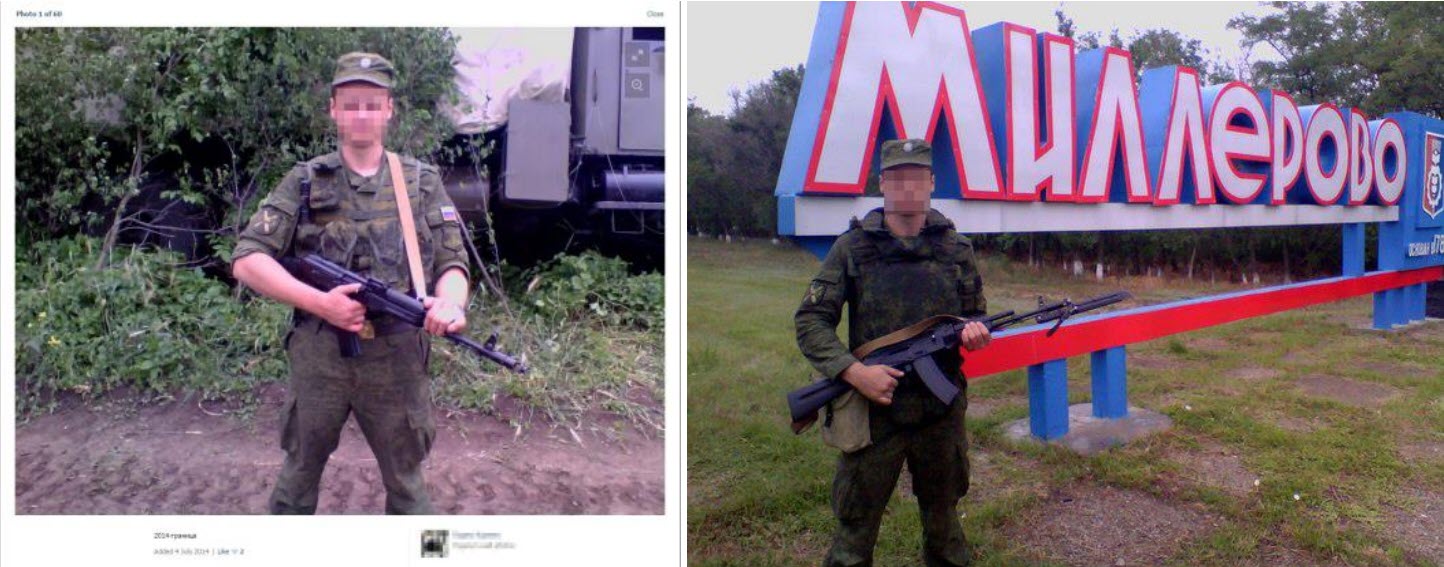

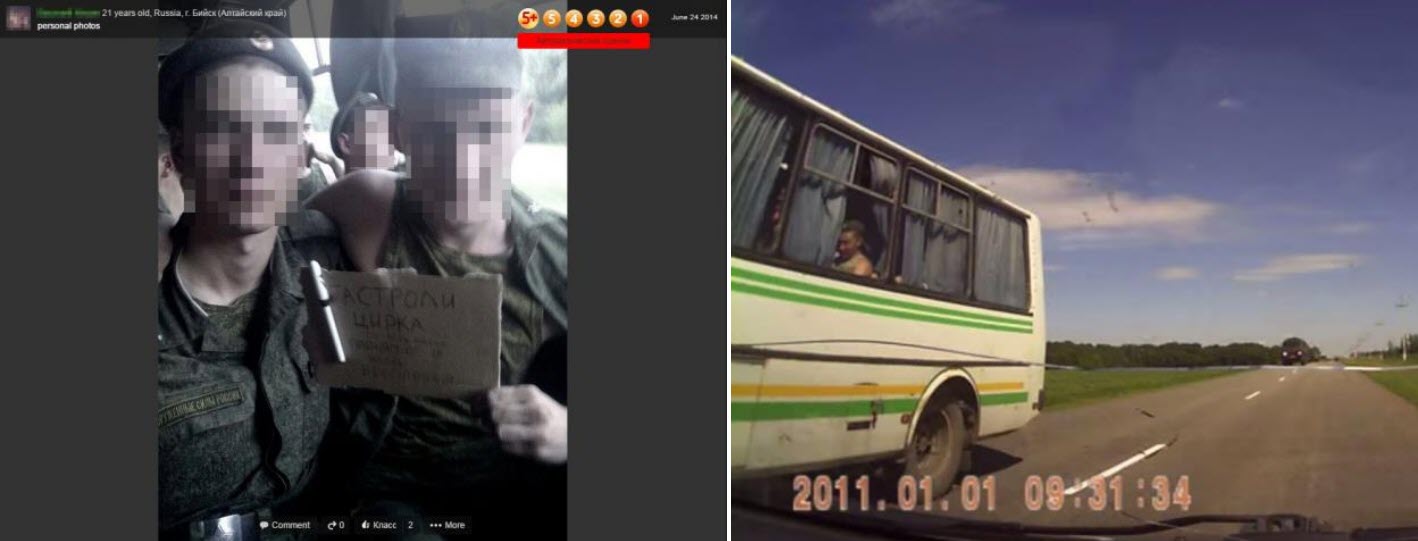

The missile launcher that downed MH17 was a part of a late June convoy that consisted of 53rd Brigade soldiers and hardware travelling from Kursk to the Russia-Ukraine border. 53rd Brigade soldiers were kind enough to meticulously detail their journey along the way and in their camp near the border by sharing photographs and videos on their VK and Odnoklassniki (OK) profiles.

Sometimes, they would make the work of geolocating their photographs very easy by posing in front of town signs.

In other instances, we were able to discover multiple perspectives on the same scene, including one from inside a bus (taken by a 53rd Brigade soldier) and a dashcam video from a Russian who uploaded a video passing by a military convoy and that same bus to his YouTube account. In the composite below, you can see the sleeping soldier’s head against the window in both images.

(The time stamp is incorrect, like how an alarm clock will say 12:00 after it is unplugged)

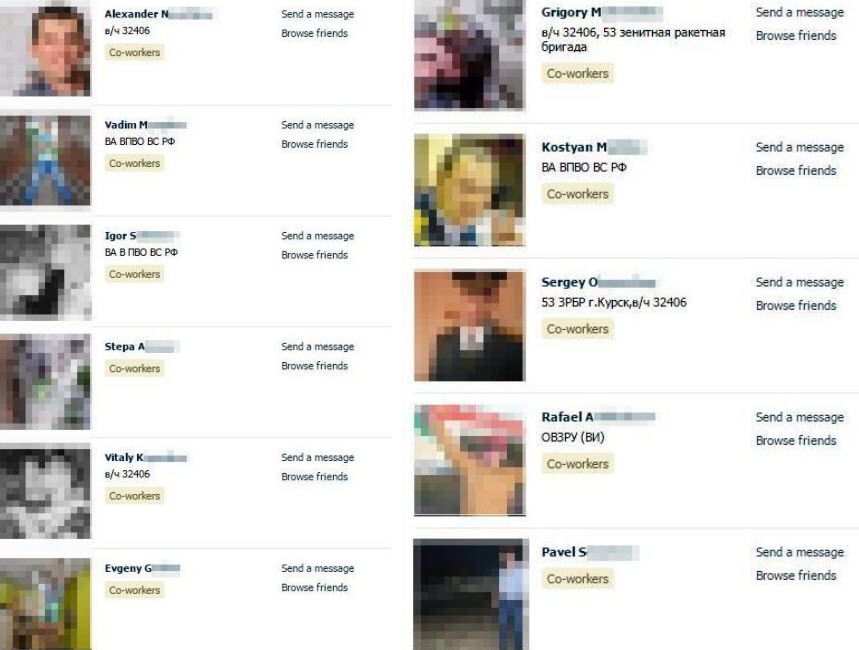

In some especially careless uploads, a list of names of cadets studying in Kursk was shared on someone’s VK account, allowing us to search each of these people individually to find their social network accounts when they did not explicitly list their affiliation with the 53rd Brigade.

Lastly, surveying the social network profiles of 53rd Brigade soldiers allowed us to reconstruct the leadership structure of the unit, thus providing an opportunity to identify who were the most likely suspects in the downing of MH17, as particular battalions within the 53rd Brigade were not present on the Ukrainian border in the summer of 2014. One 53rd Brigade officer listed his other fellow officers and commanders as “Co-workers” on his VK profile.

Through all of this information, we were able to establish a hierarchy of the officers and commanders of the 53rd Brigade’s second battalion, which was present on the Russia-Ukraine border in the summer of 2014. The full list, without any redaction, was provided to the Dutch-led criminal investigation into the downing.

Still analyzing the summer of 2014

The height of the war in Ukraine came in July-August 2014, with the deadly Battle of Ilovaysk leading to the first Minsk accords. Russian involvement peaked during this key battle, with its second surge in the January-February 2015 Battle of Debaltseve. Five years later, independent researchers are still discovering new evidence of Russian involvement during this key period, with the anonymous researcher @Askai707 leading the charge. The evidence that Askai uses in his investigations are largely from two sources: photographs and videos shared by combatants themselves (including both Russian servicemen and separatist fighters), and videos from media outlets, including both “legitimate” news organizations and newly-formed propaganda outlets, like News-Front.

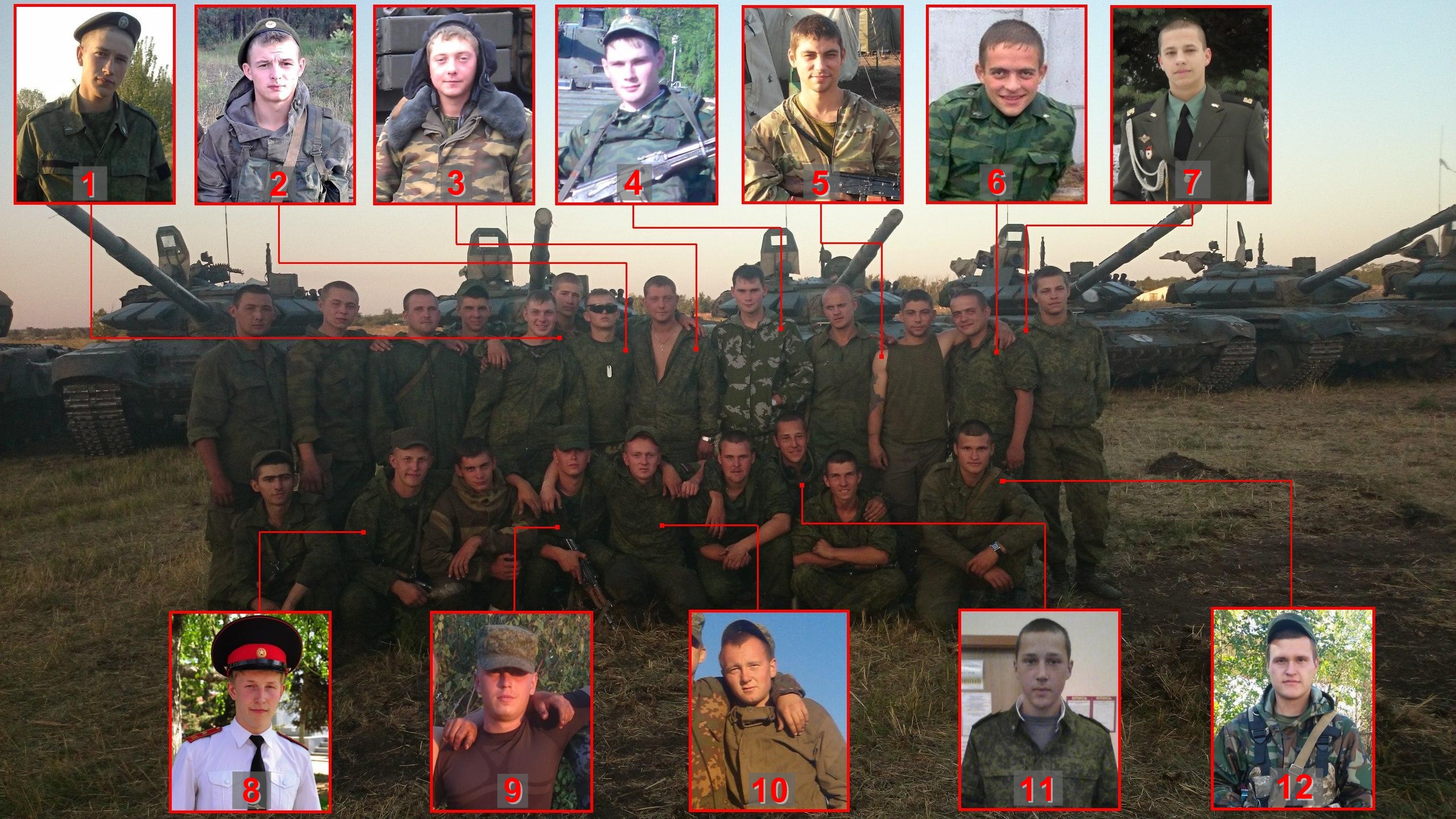

In his meticulous investigations, Askai combs through every photograph and post on the profiles of Russian soldiers and separatist fighters, picking out faces in the crowd, and geolocating photographs taken in the Donbas. For example, in one group photograph uploaded on VK by a member of Russia’s 6th Tank Brigade, Askai was able to identify nearly everyone, and then trace many of these young men to photographs and videos recorded in eastern Ukraine.

Number 8 and 9 in this group photo — Roman Gromov and Anton Yuryevich — later uploaded a photograph of themselves standing next to a sign for the Ukrainian town of Chervonosilske in eastern Ukraine.

Most Russian servicemen were not brazen or stupid enough to post such a photograph, let alone pose for it in the first place, but this did occasionally happen in 2014-5. Perhaps more common and vital to the research effort into Russian involvement in the war in eastern Ukraine is looking at the photographs of Russian soldiers back home at their base, where military equipment that was “lent” for the effort in the Donbas has been returned. For example, a Grad missile launcher that had been in Ukraine with “For Luhansk” written on the side was photographed by a Russian soldier back home in Murmansk, in Russia’s far-north.

Oversharing Heroes of Russia

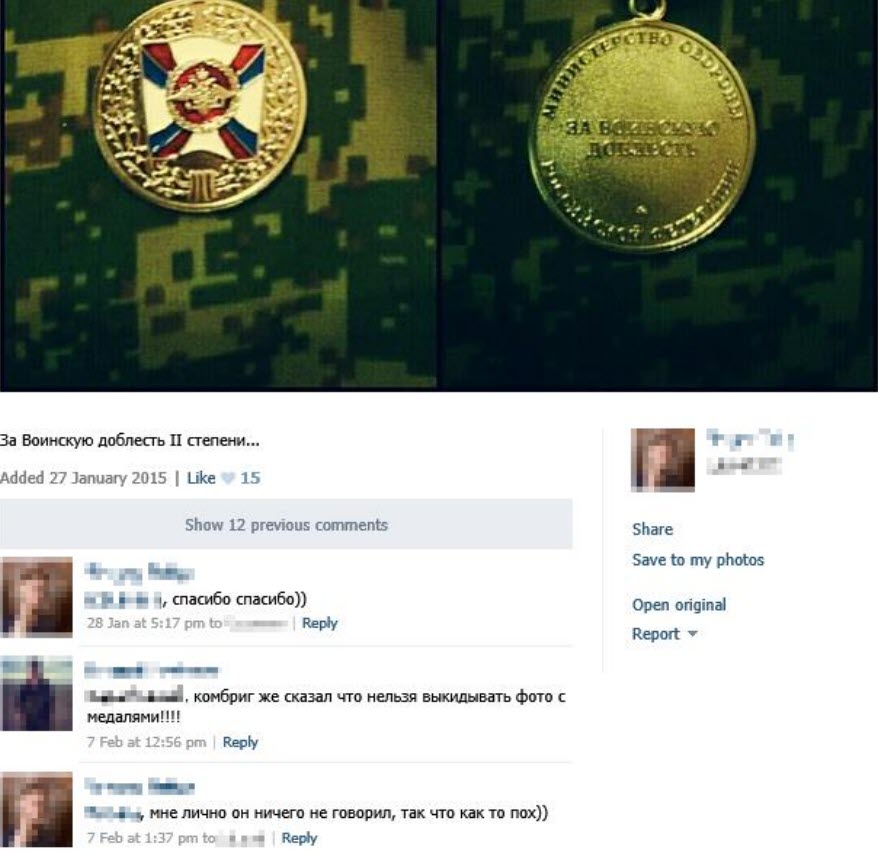

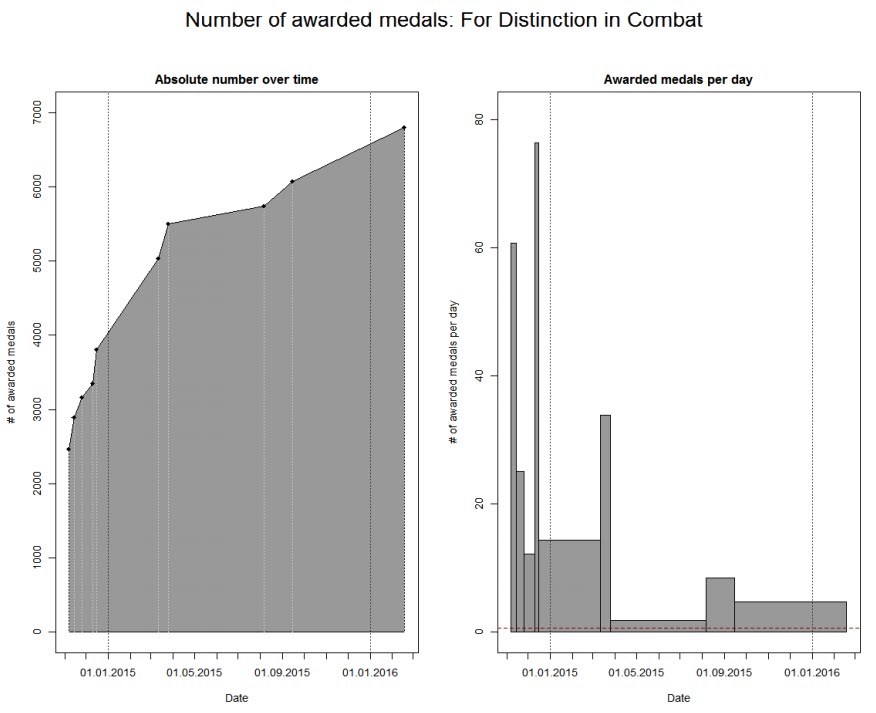

Photographs posted by soldiers during their deployments or back at their base are very useful for digital research, but social media posts made after their service ends can be just as important. In 2016, Bellingcat published an investigation using its own data set (with help from the unparalleled Askai) of medals received by Russian soldiers who likely participated in the conflict in eastern Ukraine. The vast majority of these data points were taken from posts by soldiers showing off medals and awards they had received — which includes the medal number, allowing for research in estimating the numbers of medals awarded to Russian servicemen during certain time spans.

Analysis of the data provided by these Russian servicemen revealed a huge spike in medals awarded following periods of heavy combat in eastern Ukraine, and with a notable lull in awards presented in periods not involving the conflict in Ukraine.

What’s next?

Despite the grand statements from Russian legislators, there will likely not be a significant behavioral change by Russian soldiers after this law. There has already been a great amount of pressure from the Russian Ministry of Defense to reduce smartphone usage among active servicemen, yet contraband phones will continue to pop up on bases. A trend we noticed at Bellingcat following a number of high-profile investigations around Russian activity in Ukraine was a greater use of pseudonyms or “secret profiles” from Russian soldiers to share military-related information with their close family and friends. However, as you would expect with all young men around the world, their operational security leaves much to be desired — with most of these accounts, you just scroll through the friends list of the soldiers’ siblings and parents to find the pseudonymous profile.

Additionally, even during the height of Russian servicemen oversharing information online, much of the juiciest information about Russian military activities come from people around these soldiers, rather than the soldiers themselves. Girlfriends, wives, mothers, and siblings will share photographs that they receive from their loved ones serving in the military, or overzealous fighters in eastern Ukraine operating in occupied territory will share photographs showing a Russian servicemen in the background, unaware that their face will soon be on VK for the world to see. This ban will generate lingering caution to Russian servicemen who are thinking about sharing a picture of themselves with a tank on Instagram, but at the end of the day, many of the young men targeted by this law are 19-year-old teenagers who want to make their friends back home jealous by showing off all the fun things they are doing on base or abroad. Can any law ever truly stop adolescent zeal?