Two Europol StopChildAbuse Images Geolocated: Part I — Madagascar

Europol is currently in possession of more than 40 million images of child sexual abuse from across the world. In June 2017, it launched a crowdsourcing campaign called Stop Child Abuse – Trace an Object. Through this campaign, censored extracts from explicit images are regularly published on their website and members of the public are asked to help tracing their location or country of origin.

These tips are then used to inform a competent law enforcement authority to further investigate the lead and to assist in the identification of the offender and the victim. As of October 25, 2019, Europol has received more than 24,000 tips, which have led to the identification of nine victims and the prosecution of two offenders.

In a previous article, Bellingcat wrote about the discovery of a link between one of these images and the story of a “child modelling studio” trafficking children for the production of Child Sexual Abuse Material (CSAM) in Odesa, Ukraine. On Twitter, Europol acknowledged our investigative methods which, according to them, significantly contribute to tackling online abuse.

In this new article, we will show how two new batches of images published by Europol, Group ImageG13 and Group ImageC20, have been respectively geolocated to Madagascar and Cambodia. Both locations were found to be in tourist destinations, close to hotel facilities and very likely related to sex tourism. We will present a summary of the process we followed to confirm these locations and the likely time when the pictures were taken. This is Part I of the investigation and it will deal with the case in Madagascar. The upcoming Part II will address the case in Cambodia.

Nosy Kely, Madagascar

1: The Location

Group ImageG13 was geolocated to coordinates (-20.301825, 44.266543) in Nosy Kely, a small village south of the town centre of Morondava, a city in Madagascar.

Figure 2: Group ImageG13 A & B as published by Europol on their website #StopChildAbuse #TraceAnObject. The group of images was geolocated to the village of Nosy Kely, Madagascar; just south of the town of Morondava. The red pointer indicates the approximate spot where the images were taken from. Google satellite image, 2004

2: Initial Observations

– After analysing ImageG13-A & B from Figure 2, it was determined the two could be joined to form a panoramic view of the landscape. The images were edited to obtain Figure 3. We will call this edited version ImageG13 in the text for the purpose of clarity.

– The landscape shown on ImageG13 was believed to be a beachfront.

– A row of pine trees and a group of palms were observed to the left and the right of ImageG13 respectively. The landscape showed no sign of high elevations or mountains on the horizon.

– The area covered by grey sand was large and split by a line of water along the beach. Three options were initially considered: water remaining during a low tide, flowing water coming from a river mouth or a combination of both. A few tree branches were also observed in the water body. These were likely to be mangroves as seen in Figure 4. This increased the possibility of a river mouth in the vicinity.

– A group of houses were visible along the beachfront, believed to be of rural construction. In front of one of these groups, a dark brown object was observed on the sand. This was likely to be a boat which suggested the possibility of fishing activity in the area. If this was a touristic place, there were likely to be hotels in the area.

Figure 4: Branches in the water body were observed. These were believed to be mangroves. A dark object on the sand in front of the houses was thought to be a boat which indicated possible fishing activity in the area

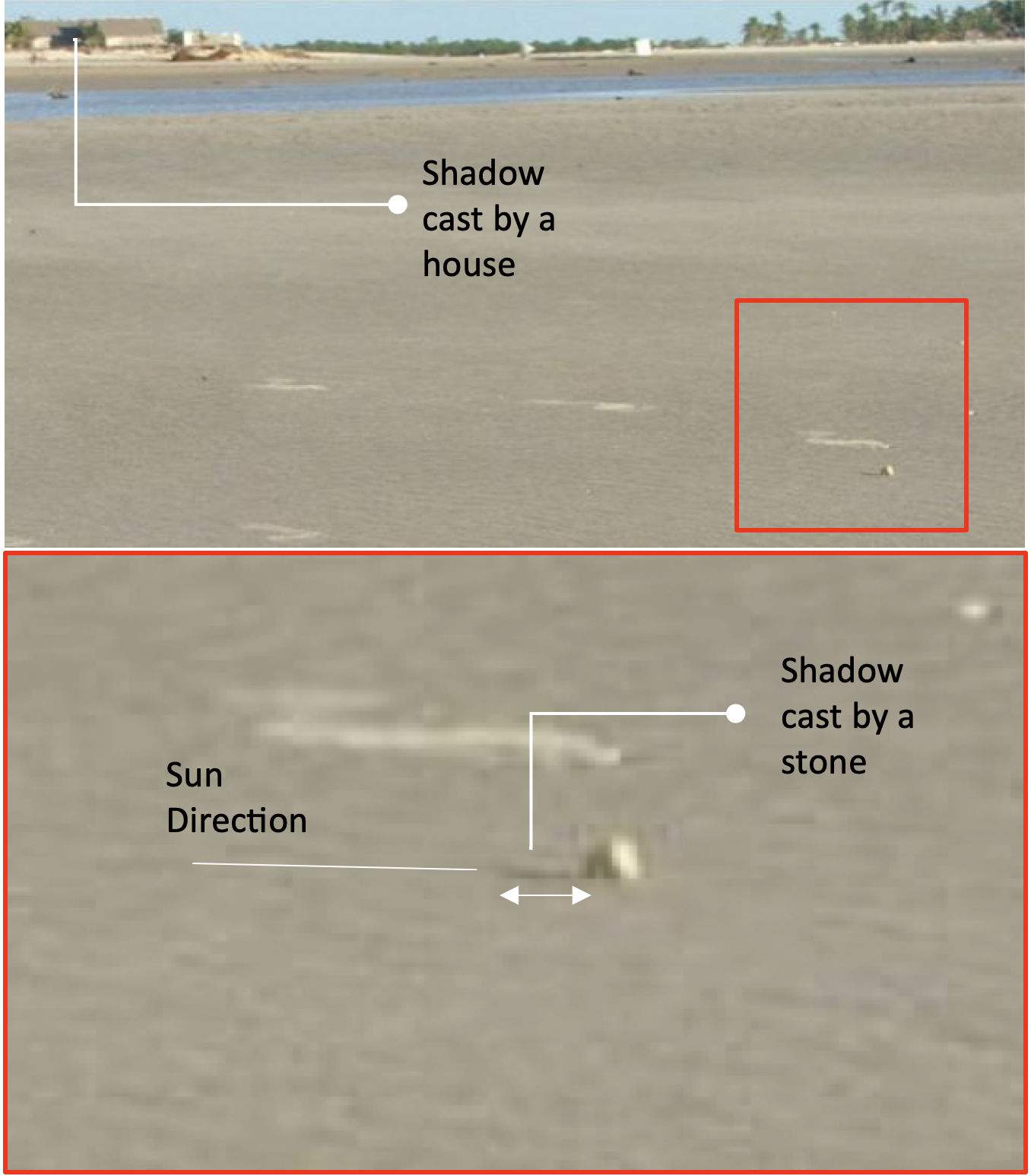

– Footprints across the sand area were visible. Close to one of the footprints, a small solid body believed to be a stone was observed as seen in Figure 5. For such a small body to cast a shadow approximately twice its height, the sun was likely to be at low altitude. ImageG13 was likely taken either in the early hours of the morning or late afternoon; with the beach likely oriented east or west respectively. The sun’s direction was also confirmed by the shadows cast by a group of houses. These observations would constitute an important element to consider when screening the coasts to explore in the following section.

Figure 5: Footprint marks across the sand area were visible. The relatively large shadow cast by a small stone on the sand suggested the image was taken in the early morning or late afternoon; with the beach likely oriented east or west respectively

3: The Screening Process

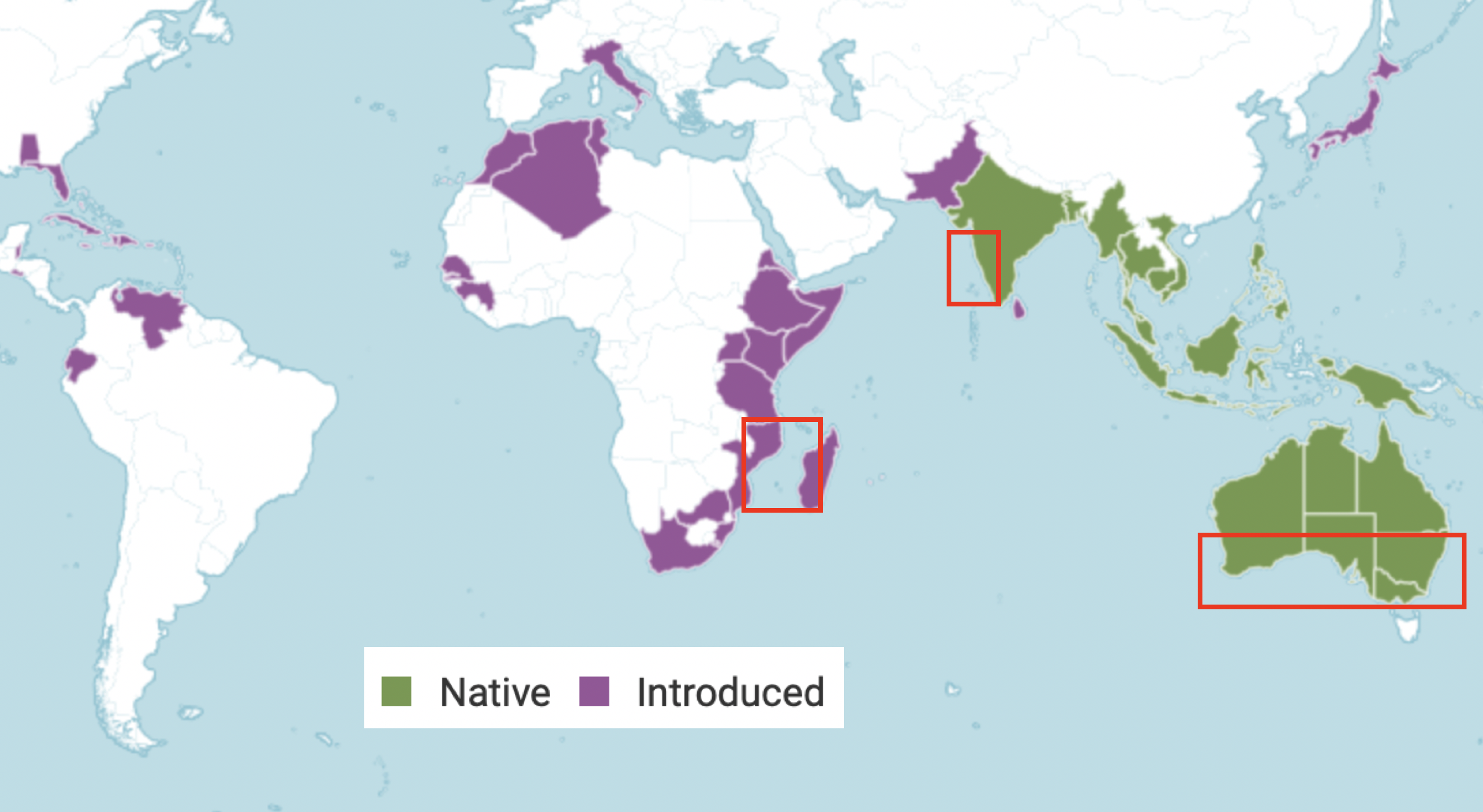

The presence of palm trees strongly suggested the location to be tropical or subtropical. Via doing some research on the pine trees, we arrived at the conclusion that they likely belong to a genus called “Casuarina” which is native to Australia, the Indian subcontinent, Southeast Asia and the islands of the western Pacific Ocean. This type of tree was also introduced to other regions — mainly in West Africa, as shown on the map in Figure 7.

Figure 6: Comparison between the pine trees [technically, she-oaks] featured on ImageG14 and an example found during the search. The tree is classified under the genus Casuarina

Figure 7: Genus Casuarina is native to Australia, the Indian subcontinent, Southeast Asia, and the islands of the western Pacific Ocean. The genus was also introduced in other regions such as West Africa

Based on this map and the initial observations in the previous section; three preliminary areas for exploration were selected in Figure 7 as a seed to start our iteration process:

- The south coast of Australia

- The Mozambique channel

- The west coast of India

The main features sought in beaches within these regions were:

- North-west or south-east orientation

- Casuarina trees along shores with very flat terrain and no mountains nearby

- Likely presence of river mouths close to the beach

- Low tides cycle

- Presence of mangroves to the front of the beach

- Rural architecture of houses or hotels

4: Geolocating ImageG13

Visually similar landscapes were found in the three regions. However, after two weeks of checking hundreds of Google Maps photos and satellite imagery on Google Earth as well as hotels on booking.com and images of beaches in Google, we found that the west coast of Madagascar shared the largest number of strong similarities with ImageG13. In specific, the coast of the Toliara Province seemed like a possible match.

A collage with a selection of these images was built in the process to assist visual recognition (See Figure 8). The type of double pitch houses, casuarina trees, river mouths, colour of sands, mangroves and boats largely matched those observed in ImageG13. Given the level of confidence the visual evidence offered, It was decided Madagascar’s coast was a potential match and warranted further investigation.

Figure 8: Image collage with landscape and architecture similarities found on the west coast of Madagascar. Zones with similar houses, palms, casuarina trees, mangroves and boats were found within the Toliara province

A Note On Child Sexual Abuse in Madagascar

In trying to narrow down the search further, geographic and demographic data on child sexual abuse in Madagascar was consulted in UN and UNICEF reports, as well a case stories and assessments from ECPAT. A brief summary of the situation is offered here:

- According to the World Bank, Madagascar is among the poorest countries in the world with 75% of the population living on less than US$1.90 per day.

- The Toliara province is one of the poorest in the country.

- The number of children exploited and prostituted continues to increase.

- Child exploitation and sexual abuse imagery affect all provinces but some specific areas can be highlighted:

- Urban: Antananarivo, Mahajanga, Toamasina, Toliara, Antsiranana

- Mining: Ilakaka, Moramanga and Tamatave.

- Tourist: Nosy Be, Diégo-Suarez, Mangily, Foulpointe, Sainte Marie and Fort Dauphin. Nosy Be is a particularly noticeable centre for prostitution/exploitation according to many sources.

- Domestic sex tourists outnumber international sex tourists.

- Sex tourism targeting children has increased in coastal cities.

- 58% of the total number of tourists are French.

- Two recent cases of child sexual abuse and CSAM production have been reported:

Case 1: A 60-year-old Frenchman abused a 13-year-old girl in Toamasina. The main perpetrator was arrested in France in June 2013.

Case 2: In 2016, two girls were sexually exploited in Nosy Be by a 59-year-old Frenchman, who police believe is part of a larger network of criminals involved in the production and distribution of child sexual abuse material. He is now in prison, awaiting extradition to France.

All the towns named above were plotted on a map of Madagascar to see if some fell in the Toliara Region (See Figure 9). Effectively three of them were but could not be matched to ImageG13. Given the level of poverty and the increasing trend in sex tourism on the island, it was highly possible for the photograph to have been taken in a touristic town.

Figure 9: A map of Madagascar. Towns highlighted in red are reported to be affected by high number of cases of child exploitation and the production of CSAM

More images and videos were analysed for each one of the most touristic coastal places in the Toliara province: Anakao, Ifaty, Andavadoaka, Morombe, Belo Sur Mer and Morondava.

A drone video filmed in Morondava showed a first close match for some of the elements featured on ImageG13. In particular; a group of houses, pine trees and a white poster located in the village of Nosy Kely.

Figure 10: A YouTube drone video offered a view of Morondava Beach in the Village of Nosy Kely. A group of houses and a white poster at the front of one of the hotels in the area were preliminary identified

A satellite image from 2004 clearly revealed a matching distribution of buildings and pine trees along the beach. Further verification of the area was carried out. A Flickr Photo from 2007 and a YouTube video revealed an exact match for all of the buildings featured in ImageG13 with the exception of the unit marked in blue as shown in Figure 11 and Figure 12. The shadows generated by a group of houses largely matched too. The approximate location of the camera was also determined.

Having identified all these elements, the location was considered verified.

Figure 11: A satellite view from 2004 compared to ImageG13. All of the buildings matched with the exception of the one marked in blue which seemed missing

Figure 12: Images of Morondava from 2007 and 2013 revealed an exact match for all the buildings featured on ImageG13. The building unit marked in blue could not be identified. Below: The shadows generated by the group of houses largely match those observed in ImageG13. The palm trees relative location with respect to the houses is also a match

Figure 13: The approximate position of the camera was determined to verify the location. Image credit: Timmi Allen

5: When Was ImageG13 Likely Taken?

The earliest satellite image available for Nosy Kely dates back to 2004. On that image, the group of houses projecting shadows on each other on ImageG13, are presented lined up in a staggered organised pattern (See Figure 14). From Google Maps, the small beach location has currently more than ten hotels and restaurants in service. Given the design of the houses and the proximity to other hotels in the area; it was believed the group of houses in question could have belonged to a hotel facility.

Figure 14: Houses featured on ImageG13 are seen lined up in a staggered pattern on satellite image from 2004. The group was believed to be part of a former hotel facility

Based on the physical condition of the houses in 2013, a preliminary estimate of 20 years was established for ImageG13. A report from the Ministère de l’Agriculture, de l’Elevage et de la Pêche provided a comprehensive list of accommodation and catering establishments in Morondava for the year 2000. Among this list, there was a hotel called Le Royal Toera. Imagery gathered from different websites revealed the group of houses indeed belonged to this hotel (See Figure 15).

According to the architects, the hotel project was completed in 1997. In January 2000, Apavou Hotels Group started managing the Royal Toera. Different sources including the operator and a travel agency website; described the facilities as having:

- One restaurant

- One pool

- Sixteen bungalows

Analysing the images found on the architects and travel agents’ websites, all 16 bungalows in the grounds of the hotel were identified. They were numbered from 1-16 and grouped according to their orientation, location and style as shown in Figure 15 and Figure 16. The restaurant and the pool were also identified.

On the west side, the hotel originally featured a pool with a bridge. Around this area, there were lamp posts which helped to determine the relative position of each of the bungalows in the analysis. Although many of the buildings found in the pictures were missing on the satellite imagery for unknown reasons; all the information was merged to produce a sketch in order to understand how the original hotel layout could have looked like (See Figure 17).

Figure 15: Buildings in the grounds of the hotel were identified using images of the hotel between 1997-2000. Only eight bungalows out of the original 10 in the north group are visible on the satellite view from 2004. Here, the restaurant and other 6 bungalows from the south group are all missing. Bungalows 1 & 2 feature no roof in ImageG13

Figure 16: Buildings in the grounds of the hotel were identified using images of the hotel between 1997-2000. The original pool and its bridge were also identified on satellite image. On the latter, the restaurant and the south group of bungalows are clearly missing

Figure 17: Sketch with an approximation of how the original layout of the hotel could have looked like. The diagram is based on imagery found of the facilities and satellite images from 2004

From Figure 15, it can be noticed that ImageG13 features bungalows 1-10. However, bungalows 1 & 2 seem to have no roof.

Also, according to the field of view and position of the camera calculated in the previous section, the restaurant unit should have been visible on ImageG13 as well, but instead, the whole building is missing. Bungalows 1-2, the restaurant and bungalows 11-16 are missing on the satellite view from March 2004. In order to know when ImageG13 was taken, it was necessary to understand what sequence of events changed the layout of the hotel so drastically.

Establishing A Timeline

Between the 11th and the 16th of March 2000, a German tourist wrote in his travel journal about his arrival to the Royal Toera Hotel and made the following observations:

- Confirmed the hotel had 16 bungalows.

- The swimming pool and restaurant were fully operational.

- There were palm trees all around the facility but they were not higher than 1.5 m.

- There was no beach immediately in front of the hotel, but a rough sea instead.

- Workers had been repairing a breakwater/promenade structure at the waterfront that was affected by cyclones in the previous weeks.

- In discussion with the owners of one of the local restaurants, he described how sex tourism was affecting the town. Some tourists looked for girls as young as 14 years old.

We discussed earlier that bungalows 1-2 are shown with no roof in ImageG13. Given the fact that the German tourist described the relatively good conditions of the hotel facilities including the restaurant, pool and the 16 bungalows after recent cyclones; ImageG13 was most likely taken after March 2000 but before the bungalows 1-2 disappeared completely as shown in satellite images from the 25th of March 2004.

Although not conclusive but rather informative, it was considered important to highlight a couple of findings and key facts which will be discussed later in the report:

- A Curriculum Vitae from a former employee of the hotel indicates he stopped working for the Royal Toera in May 2002.

- In 2008, a TripAdvisor user received information about the Royal Toera having burned down several years ago. A local source who cannot be named affirmed that the fire in question only destroyed the restaurant of the hotel. The same source indicated that sometime after this event the south group of bungalows and the pool were destroyed by a cyclone. Unfortunately, no specific dates were recalled.

- Between April and June 2002, Apavou Hotels Group stopped advertising their operations in Madagascar and Mayotte (including the Royal Toera). According to the news, the management contract of the hotel should have run until 2005.

- Presidential elections were held in Madagascar on 16th of December 2001, leading to violence between supporters of two candidates. The conflict lasted until July 2002.

- Prostitution represents a serious problem in the village. In 2008, Morondava was reported to be the home to at least 200 sex workers, from which at least 50% were in fact minor victims of exploitation. Night clubs and bars in Nosy Kely were frequented by sex workers to meet tourists or Malagasy visitors.

Morondava is an area at high risk of flooding and severe coastal erosion. Different environmental factors including cyclones, strong tides, heavy rains, drought and human activities have created an imbalance in the flow of the nearby rivers, generating a severe effect of marine erosion of the coastal sector. The mouth of the river where the Royal Toera Hotel was located is particularly sensitive to maritime submersion and flooding. More information can be found in this paper and a project for protection and mitigation of the littoral in Morondava called PALM.

In an article from The Guardian from 2016, the situation above is discussed. An image in the article depicts the ruins of what they called “The remains of a hotel and swimming pool that was flooded several years ago by rising sea tides in Morondava”. It was determined the structures described belonged to the Royal Toera Hotel (See Figure 18).

Figure 18: The Royal Toera photographed by The Guardian in 2016. The hotel was reported to have been flooded but no specific dates are given in the article

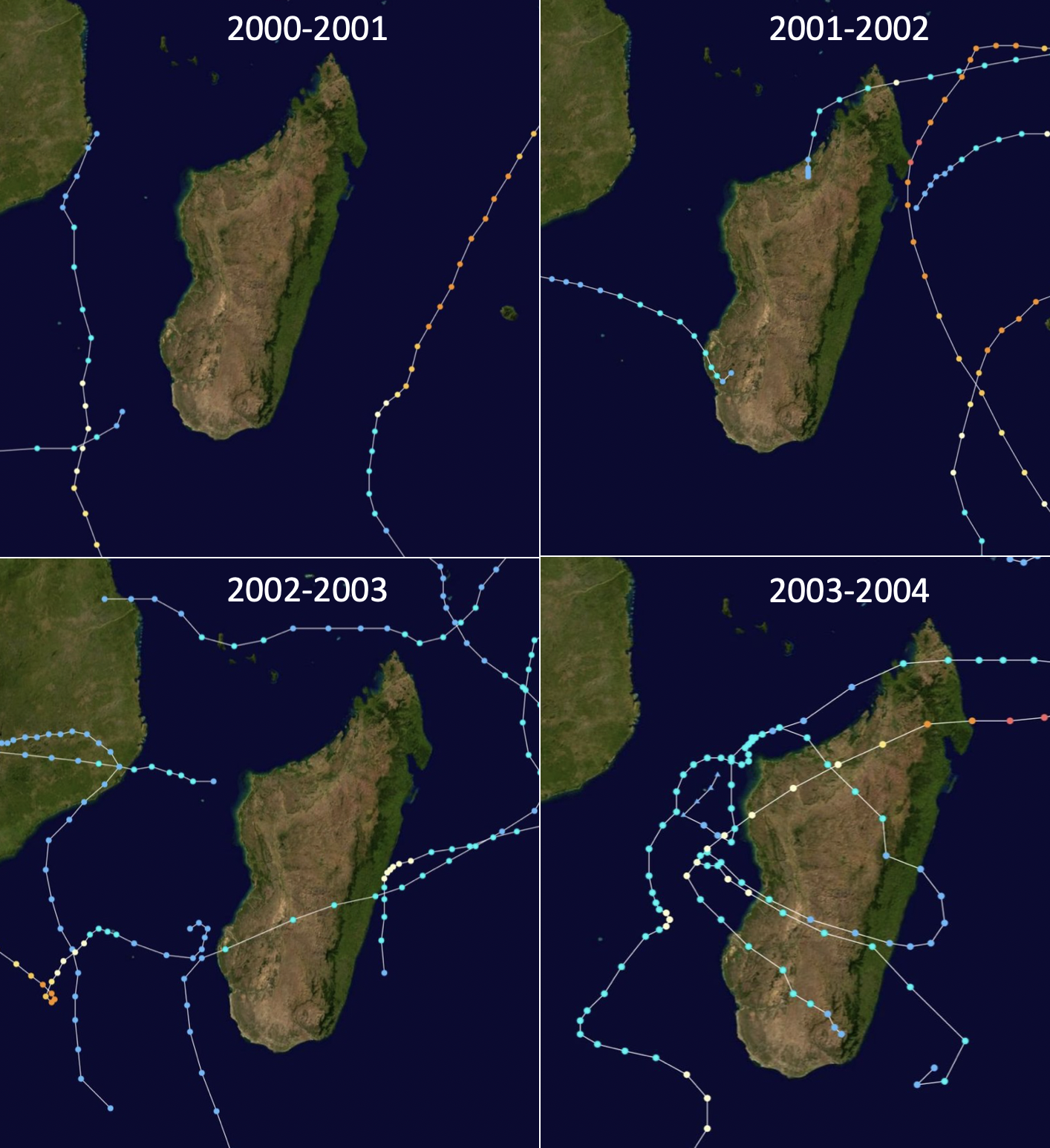

Despite the fact that no specific dates were obtained via the sources consulted, the destruction of the hotel was most probably linked to flooding and cyclone events in the area. Southwest Indian Ocean cyclone seasons 2000-01, 2001-02, 2002-03 and 2003-04 were investigated and a summary of the activity around Madagascar is shown in Figure 19. From all the cyclones and storms investigated, only Cyprien in 2002, as well as Elita and Gafilo in 2004, are reported to have caused major damage in Morondava.

In Table 1, a timeline has been created with a summary of the information gathered about the country and the hotel operation, as well as cyclones and storms which are reported to have caused severe flooding in Morondava between 2000-2004. The chronological order of the observations strongly suggests that ImageG13 might have been taken between January 2002 and March 2004.

Table 1: Construction of a timeline for cyclones, storms, events and observations related to the Royal Toera Hotel between 2000-2004

Verification Of The Proposed Timeline

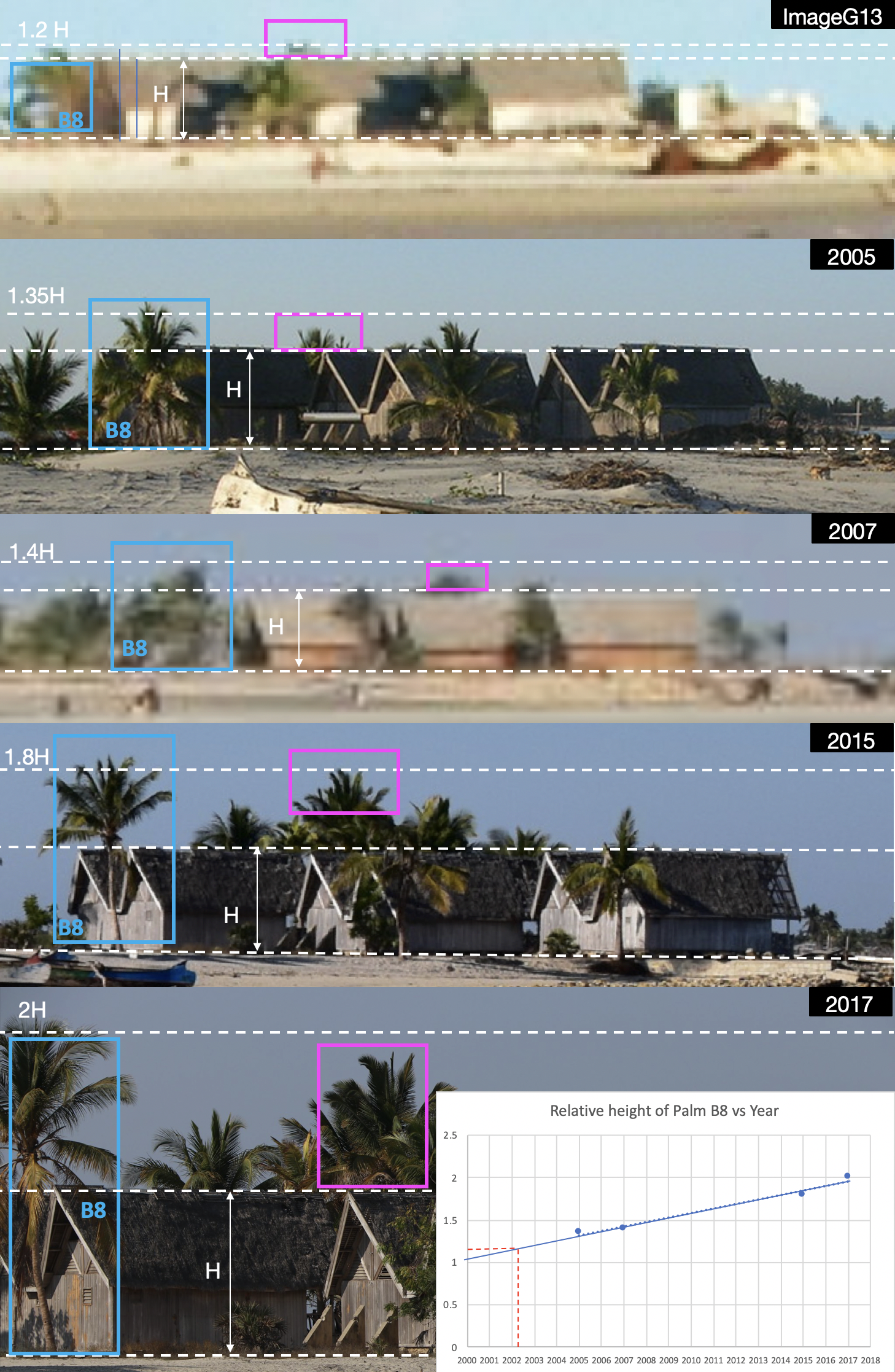

On ImageG13, bungalows 3 to 8 show palm trees on their north side. One of these trees was clearly identified in other images produced between 2005 and 2017. For simplification, this palm has been labelled “B8”.

Given that all images were taken from the distance at a similar angle and although the growth rate of a tree is probably not linear as it depends on many factors; a simplified calculation was proposed to determine an approximate year when ImageG13 was produced.

The height of B8 was measured for each one of the shots as a linear proportion of the bungalows’ height (H) (See Figure 20). The results were plotted for each year and a linear equation obtained to calculate the year when B8’s height was 1.2 H, as observed in ImageG13. The resulting year, 2002, fits into the timeline presented in Table 1.

Figure 20: Bungalows 3-8 pictured in different years. A simplified linear equation (based on the observed growth rate of Palm tree B8) was used to estimate the year when Palm B8 had the height observed on ImageG13. The resulting year, 2002, fits into the timeline of events

Conclusion: Part I ImageG13/Nosy Kely, Madagascar

The geolocation process for ImageG13 took approximately 3 weeks in total. Further investigations were carried out to determine the year when the image was taken, which then extended the investigation for a further 2 months.

The location was identified to be in Nosy Kely, Madagascar; near a now partially destroyed hotel, formerly known as Royal Toera. Despite no specific reports or images about damages caused to the hotel were found during this investigation, a timeline was created with relevant events to determine how the hotel could have been destroyed.

All buildings, which used to belong to the hotel, were identified and drawn on a sketch using images available on the internet. Ten of these buildings are featured on ImageG13 with two of them presenting no roof.

It is very likely that the hotel was impacted by the severe tropical storm Cyprien in January 2002. As a result, the roof of bungalows 1 & 2 might have been damaged. In 2004, after the landing of much stronger cyclones like Elita and Gafilo, a dam collapsed upstream a nearby river and caused severe flooding in the area. This most probably damaged the rest of the south and west wings of the hotel, including the pool as seen on Satellite images taken 2 weeks after the cyclone Gafilo.

Apavou Hotels Group stopped advertising the Royal Toera Hotel in 2002. While in the middle of a serious political crisis in the country and hit badly by two cyclones in the same year, the management of the hotel might have decided to implement changes in the business that either justified the end of contracts and employment of staff; or, in a worst case scenario, the final closure of the hotel. This subject deserves further investigation.

A dimensional analysis applied to a palm tree, observed on ImageG13 and other images of the same location for different years, helped to support the timeline proposed.

Based on the evidence discussed, it has been determined that ImageG13 was most likely produced between January 2002 and March 2004. Given the number of hotels and bars in the area during this period and the reported levels of exploitation of minors, it is also very likely the image was related to sex tourism.

This report will continue with the second part of the investigation, which is due shortly:

Part II – ImageC20 Siem Reap, Cambodia

Research by Carlos Gonzales, Daniel Romein, Timmi Allen and “Bo”